Richmond Carers Needs Assessment 2019

This document is also available in PDF format: LBRuT Carers Needs Assessment 2019

Executive Summary

A carer is someone of any age who, without payment, provides help and support to a partner, child, relative, friend or neighbour, who could not manage without their help. This could be due to older age, physical or mental illness, drug or alcohol misuse, or disability.

Young carers are children and young people under the age of 18 who are taking on practical and/or emotional caring responsibilities normally expected of an adult, and can include anything from cooking, shopping and housework to administering medication, assisting with personal care such as washing or dressing, interpreting, physical support such as lifting and even emotional support or looking after younger siblings.

National priorities for carers were outlined in the National Carers Strategy 2010:

• Supporting those with caring responsibilities to identify themselves as carers at an early stage, recognising the value of their contribution and involving them from the outset both in designing local care provision and in planning individual care packages.

• Enabling those with caring responsibilities to fulfil their educational and employment potential.

• Personalised support both for carers and those they support, enabling them to have a family and community life.

• Supporting carers to remain mentally and physically well.

These have been refreshed in the National Carers Action Plan 2018-2020, which highlights five priority areas for action:

• Services and systems that work for carers

• Employment and financial wellbeing

• Supporting young carers

• Recognising and supporting carers in the wider community and society

• Building research evidence to improve outcomes for carers

This Richmond Carers Needs Assessment aims to provide a greater understanding of the characteristics and needs of carers in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames by providing:

1. A profile of carers, including the number and characteristics of carers in Richmond upon Thames; and the social, economic and health impact of caring and the results from initiatives that involved carers.

2. An overview of local services for carers in Richmond upon Thames, and insight into the access to and utilisation of these services.

Key Findings

Key characteristics of unpaid carers in Richmond upon Thames include:

• 15,802 (8.5% of all residents) identified themselves as carers. This is similar to the London average (8.5% across all London boroughs), and lower than the average in England.

• Three quarters of carers provides care for 1-19 hours a week, 10% 20-49 hours and 15% more than 50 hours.

• There are more female than male carers (59% of carers are female).

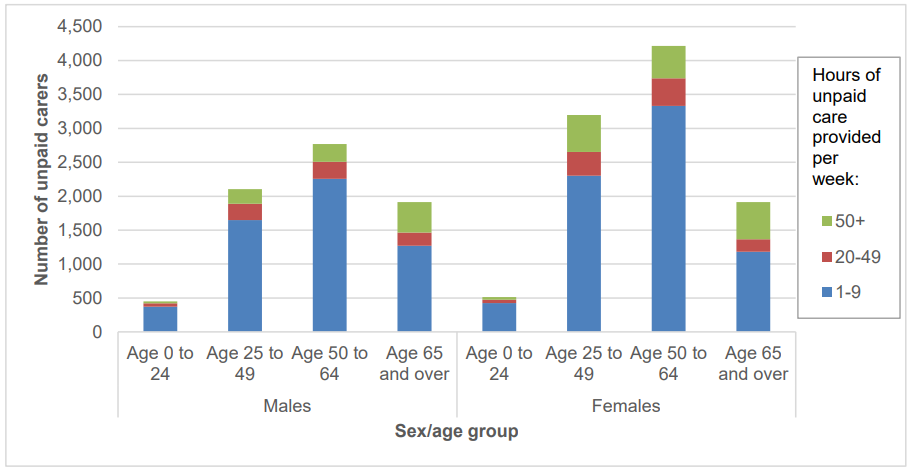

• The peak age for caring is 50-64 years. 34% of carers are aged between 25 and 49 years, 38% between 50 and 64 years, and 22% are aged over 65 years. Six percent of carers are younger than 25 years.

• Carers are more likely to report health problems: 20% of carers report poor health, compared to 11% of those who do not provide care.

• While 60% of carers are economically active, providing care is often a reason for unemployment or for working part-time.

Services that are currently available for carers in the borough include:

• Carer-specific services: the Carers Hub Service; carers assessments; carers break payments; carers emergency card; shared lives dementia scheme and telecare/careline and emergency alarms. Carers are also eligible for a free flu jab.

• Services for all Richmond upon Thames residents, including carers, such as the Richmond Wellbeing Service, and NHS Health checks.

The number of carers reported in the 2011 Census (15,802; 8.5%) is much higher than the number of carers that have been identified in general practice (1,683 in September 2018), in the voluntary sector (around 1,800 adult carers identified by the Carers Hub Service) and by social care (298 adults carers had a carer’s assessment in 2016/17).

Challenges

The findings from the Richmond Carers Needs Assessment (RCNA), and additional national surveys and research, have highlighted a number of challenges in service provision and delivery to be investigated. These findings will inform the 2018-2021 Richmond Carers Strategy.

• Local knowledge on specific cohorts of carers

There are a number of gaps in our understanding of specific cohorts or carers including those caring for people living with autism, co-morbidities and both parents and children.

• Up-to-date monitoring information on Carers Assessments

• Financial wellbeing

There is a lack of information on the financial wellbeing of carers in Richmond, and services tailored to this. National surveys indicate this is a key issue, in a recent survey 37% of carers described their financial situation as ‘struggling to make ends meet’, and of this group 47% said they cut back on essentials such as food and heating to cope (Carers UK, State of Caring 2018).

• Social isolation and recognition

Social isolation is a pressing concern felt by many carers, and often services are unable to alleviate this. 73% of carers felt their role was not valued or understood by government (Carers UK, 2017) and carers, especially those aged 65 or older, are at risk of social isolation (Brodaty, 2009), In Richmond-upon-Thames just 29.7% of carers aged 65 and over report having as much social contact as they want, compared to 36.3% of carers aged 18 to 64 (Survey of Adult Carers in England, 2016/17). This is a pressing concern for the local population as 60% of carers are aged 50 or older.

• Transition

Transitions within the caring role, such as going from caring to no longer having caring responsibilities, or from being a young to an adult carer, are often neglected within research and studies conducted around caring. There is limited data around the numbers of young carers who transition into adult carers, or away from caring. More could be done to tailor services to carers in these scenarios and help carers manage changing relationships and responsibilities.

• Health needs of older carers

The number of carers aged over 65 years is increasing more rapidly than the general carer population and of those who provide more than 50 hours of care a week 39% are older than 65 in Richmond (ONS, 2011). Older carers are also more likely to have long-term health conditions than younger carers (in Richmond upon Thames 67.4% of carers aged 65 and over reported having at least one long-term health condition compared to 53.3% of carers aged 18 to 64 (Survey of Adult Carers in England, 2016/17)). This is therefore a key group to target and develop services for, and more could be done to highlight how this is being considered, beyond offering free health checks.

• Negotiating complex systems

The RCNA has highlighted issues of duplication, lack of communication with referrers and carers, and no clear path following assessment. Carers also report facing difficulties in negotiating these systems on behalf of the person being cared for.

Recommendations

Key recommendations arising from the RCNA will be addressed in the Carers Strategy

Developing integrated services and systems that work for carers

Duplication of assessment and advice often complicates a carer’s engagement with support services. As advocates for those they care for and as recipients of services themselves, it is essential that carers are able to access appropriate services in a timely way. Organisations should prioritise efforts to link systems and build robust monitoring procedures to assess and share data on the quantity and quality of carers assessments. Furthermore, the accurate recording and monitoring of the use of services is important so that their accessibility and quality can be maintained and improved.

• Improving the identification of carers

The number of carers reported in the 2011 Census is much higher than the number of carers that are identified in general practice (health), the voluntary sector and in social care. National engagement and consultation shows that many carers do not consider themselves a carer. Increasing the identification of carers is a key priority in the Carers Strategy.

• Supporting carers in employment

Developing carer friendly employer policies, and information and advice for employers on what caring responsibilities entail and how to accommodate and support carers in the workforce, should be a priority for local organisations.

• Supporting young carers

Young carers are more likely to struggle with educational attainment and may find it difficult to find employment or higher education opportunities as they get older. Therefore, clear pathways should be developed to assist young carers throughout their caring role, and in transitioning from young to adult carer, or away from caring.

• Providing relevant advice, information and support

A range of services is available for carers, but the uptake of these services by carers should be improved. Clearer guidance on how to access information on continuing healthcare, issues around consent and capacity, funding and benefits, legal issues, financial advice, would also be beneficial.

• Recognising and supporting carers in the wider community

Local support networks and communities can play a considerable role in boosting the mental health and wellbeing of carers and can allow carers to navigate local services and organisations much more easily. Best practice guides should be developed to assist local groups and businesses to become carer-friendly.

• Improving carers’ health and wellbeing

Carers are more likely to report health problems. Existing wellbeing services available for all residents will be promoted among carers, as well as awareness programmes to help carers acknowledge health issues that may be caused by their caring role.

1. Introduction

This RCNA focuses on the needs of people who provide unpaid care in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.

A carer is someone of any age who, without payment, provides help and support to a partner, child, relative, friend or neighbour, who could not manage without their help. This could be due to older age, physical or mental illness, drug or alcohol misuse, or disability.

Young carers are children and young people under the age of 18 who are taking on practical and/or emotional caring responsibilities normally expected of an adult, and can include anything from cooking, shopping and housework to administering medication, assisting with personal care such as washing or dressing, interpreting, physical support such as lifting and even emotional support or looking after younger siblings.

1.1 Aims

This report aims to provide a greater understanding of the characteristics and needs of unpaid carers in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It includes:

- A profile of unpaid carers, including the number and characteristics of carers in Richmond upon Thames; and the social, economic and health impact of caring and the results from initiatives that involved carers.

- An overview of local services for carers in Richmond upon Thames, and insight into the access to and utilisation of these services.

1.2 Methods

The main data sources that have been used are the 2011 Census, the 2016/17 Survey of Adult Carers in England, the Survey of Carers in Households, Richmond Young People’s Survey, and a range of other local data sources on causes of disability and illness.

2011 Census

The 2011 Census included the following question on caring:

Do you look after, or give any help or support to family members, friends, neighbours or others because of either long-term physical or mental ill-health/disability, or problems related to old age?

[Do not count anything you do as part of your paid employment]

- No

- Yes, 1-19 hours a week

- Yes, 20-49 hours a week

- Yes, 50 or more hours a week

In addition, the Census included questions about age, sex, ethnicity and general health.

Survey of Adult Carers in England

This national survey takes place every other year. It is conducted by Councils with Adult Social Services Responsibilities (CASSRs) and published by NHS Digital. The survey seeks the opinions of carers aged 18 or over, caring for a person aged 18 or over, on a number of topics that are considered to be indicative of a balanced life alongside their unpaid caring role. The 2016/17 report used data collected from a sample of 55,705 carers who participated in the survey and these are weighted to make inferences about the whole, weighted eligible population (341,515) of carers. A total of 220 carers from the London Borough of Richmond-upon-Thames participated in the survey.

Survey of Carers in Households

In 2009/2010, a detailed survey in households (the Survey of Carers in Households) was conducted by the Department of Health as part of the Government’s Carers’ Strategy programme (Health & Social Care Information Centre, 2010). Face-to-face interviews were carried out in a representative sample of homes in England (response rate 76%). The survey included a total of 2,200 carers nationally.

This survey includes information on the characteristics of the people who are cared for, including their age, their health and their relationship to the care-giver. Given that this was a national survey without a local sample, data can be quoted directly for England, but are imputed (estimated) for Richmond.

Young People’s Survey

The Richmond Young People’s Survey was developed by the Schools Health Education Unit (SHEU) in partnership with the Richmond upon Thames Education, Children’s and Cultural Services and the Primary Care Trust, to obtain pupil’s views regarding healthy eating, safety, emotional wellbeing and leisure time. The 2014 survey included 2,801 pupils from primary, junior, and secondary schools. The survey includes questions on providing care for someone at home on a regular basis who is unable to care for themselves.

2. Background

2.1 Impact of being a carer

Most of us will look after an elderly relative, sick partner or disabled family member at some point in our lives. This invaluable service undoubtedly ensures the continued health, wellbeing and comfort of many people who are cared for, however the social, financial and health impacts upon carers can be considerable. People providing unpaid care are unable to protect their current and future financial security (Carers UK, 2017). Those providing care for more than 50 hours a week are twice as likely to be in bad health as non-carers and 3 in 5 carers have a long-term health condition (GP Survey, 2016). This impact is frequently exacerbated by carers being unable to find time to attend medical appointments, or delaying them, due to ongoing caring responsibilities. Therefore, it is essential that services and systems work for carers and are informed by their health and wellbeing needs.

2.2 Valuing carers

The vast majority of care is provided by family, friends and relatives, and the care they provide is worth an estimated £132bn per year (Carers UK, University of Sheffield, University of Leeds, 2015)– notably more than total spending on the NHS, which was 124.7 billion in 2017/18 (Carers UK and the King’s Fund, 2017). There are 5.8 million carers in England and Wales (ONS, 2011) and Carers UK estimate that this number will need to increase to 9 million by 2037 in order to meet demand (Carers UK, 2017) However despite the significant contribution carers are making to society and the health system, the 2017 State of Caring Survey found that 73% of carers felt that their contribution was not valued or understood by government. Therefore, it’s vital that carers are given the recognition and support they need to continue to provide care.

2.3 Characteristics of Carers in the UK

For the UK as a whole, the 2011 Census suggested that:

- The total number of carers had grown from 5.2 million (10.0% of UK population) in 2001 to 5.8 million (10.2% of UK population)

- The number of carers aged over 65 years was increasing more rapidly than the general carer population (Carers UK and the University of Leeds, 2011).

- Women were slightly more likely to provide care than men.

- Carers and the cared for could be categorized into three main groups:

-

- Young & young adult carers caring for a family member, commonly a parent or sibling.

- Parents caring for an adult child.

- Middle aged children & older spouses caring for older people.

Table 1. Who do carers care for?

| Caring for: | Percent (%) |

| Parents/parents-in-law | 40 |

| Spouse/partner | 26 |

| Child | 13 |

| Friend or neighbour | 9 |

| Other relative | 7 |

| Grand-parent | 4 |

| Other | 1 |

| 100% |

Source: (The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010)

- Most carers care for one person (83%). However, 14% care for two people and 3% are caring for three or more people (The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010a).

- A Department for Education report indicates that 55% of young carers provide care to a parent, whilst 25% are providing care to a sibling. 80% of these young carers are helping with practical tasks, such as cooking and household chores. Responsibilities for caring increase with age (Department for Education, 2017).

- Young & young adult carers are at risk of being hidden and not receiving appropriate support.

- Parent carers often do not identify themselves as carers and so may not always be aware of the support available to them (Carers UK, 2006a; Carers UK, 2006b). Data from the 2016 State of Caring Report shows that 37% of parent carers, compared to 24% of all carers, took longer than 5 years to recognize themselves as a carer (Carers UK, 2016)

- ‘Sandwich carers’ – those who combine care for an older relative with a range of other responsibilities, such as looking after their own children or caring for another family member or friend, often don’t identify as carers. Higher numbers of this group are caring from a distance.

- Carers of older people make-up approximately three-quarters of all carers (Pickard, 2008)., and middle-aged carers may also have dependent children in addition to caring responsibilities for older parents.

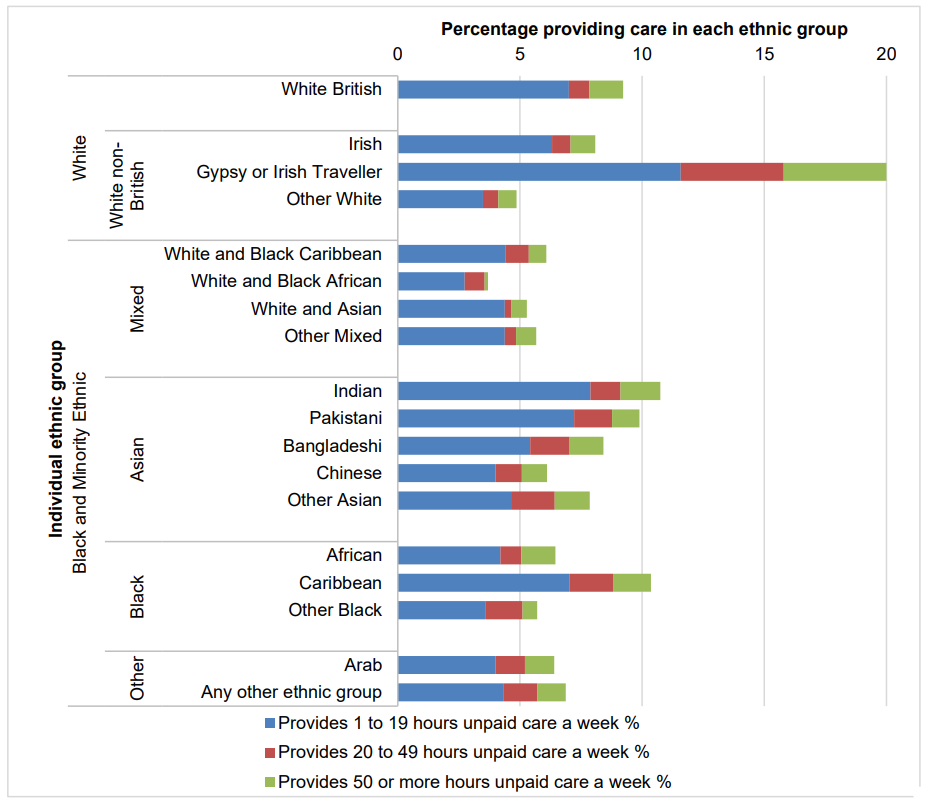

- In terms of ethnicity British (11.1%), Irish (11.0%), and Gypsy/Irish Travellers (10.7%) were most likely to be providing unpaid care; and Mixed White and Black African (4.9%), Chinese (5.3%), and Mixed White and Asian (5.3%) were least likely (ONS, 2013b). Gypsy/Irish Travellers were more likely than any other ethnic group to provide more than 50 hours of care per week.

- Wide regional variations are seen in terms of levels of caring across the UK associated with population age, disability, and deprivation (ONS, 2013c).

- The Survey of Carers in Households found the most common conditions of people being cared for were physical disability, long-standing illness, and sight or hearing loss, (see table 2). This is mirrored in the Survey of Adult Carers 2016/17 which lists physical disability as the most common condition among people being cared for (53.1%).

Table 2. Conditions of people who are cared for

| Condition cared for: | Providing care for under 20 hours per week | Providing care for 20 hours or more per week | Total |

| A physical disability | 56% | 60% | 58% |

| Long-standing illness | 32% | 42% | 37% |

| Sight or hearing loss | 21% | 18% | 20% |

| Problems connected to ageing | 25% | 9% | 17% |

| A mental health problem | 11% | 15% | 13% |

| A learning disability or difficulty | 6% | 17% | 11% |

| Dementia | 11% | 8% | 10% |

| Terminal illness | 3% | 5% | 4% |

| Alcohol or drug dependency | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Other | 1% | 1% | 1% |

Source: (The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010a)

Further national characteristics indicated by the Survey of Adult Carers in England 2016/17 show that:

- The largest proportion of carers are aged 55-64 (24.2%) and the smallest are aged 18-25 (1.4%).

- 58.5% of carers spend more than 35 hours per week providing care and 35.7% are providing care for more than 100 hours a week. This represents a considerable commitment when considered with the statistic that the majority of carers (65.2%) have been providing care for more than 5 years.

2.4 Carers in National Strategy

The intended outcomes of the coalition government’s National Carers Strategy (Cross-Government publication, 2010) were that by 2018 every carer should be:

- Recognised and supported as an expert care partner

- Enjoying a life outside caring

- Not financially disadvantaged

- Mentally and physically well, treated with dignity

- Children will be thriving, protected from inappropriate caring roles.

To achieve the above outcomes the National Carers Action Plan 2018-2020 outlines a range of cross-governmental actions based around five key themes:

- Services and systems that work for carers

- Employment and financial wellbeing

- Supporting young carers

- Recognising and supporting carers in the wider community and society

- Building research and evidence to improve outcomes for carers

The Care Act 2014 came into force in April 2015, with some elements delayed until April 2016. It put

in place significant new rights for carers in England including:

- A focus on promoting wellbeing.

- A duty on local councils to prevent, reduce and delay need for support, including the needs of

carers. - A right to a carer’s assessment based on the appearance of need.

- A right for carers’ eligible needs to be met.

- A duty on local councils to provide information and advice to carers in relation to their caring

role and their own needs.

The Children and Families Act 2014 gives young carers and young adult carers in England a right to a

carer’s assessment and to have their needs met (if the assessment shows this is needed). The Care

Act and the Children and Families Act combine to ensure the needs of the whole family are met and

inappropriate or excessive caring by young carers is prevented or reduced. The rights of parent

carers have also been addressed within the Children and Families Act. A local council has a duty to

provide an assessment to a carer of a disabled child aged under 18 if it appears that the parent carer

has needs, or the parent carer requests an assessment.

3. The carer population in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

This section gives an overview of the number of carers in Richmond upon Thames and the

characteristics of carers and the people that they care for.

While it is expected that most carers will provide care locally, carers living in another local authority may

provide care for people living in Richmond upon Thames, and carers living in Richmond upon Thames

may provide care for people living in another local authority. As we do not have data on the where the

person that is cared for lives, in this section we focus on carers living in Richmond upon Thames (who

may provide care in Richmond upon Thames or in a different area).

3.1 Estimated number of carers resident in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

3.1.1 Total number of carers in Richmond upon Thames

The population of Richmond upon Thames in 2011 was 187,000 (including 2,900 who are resident in

communal establishments) (ONS, 2011) As of 2018 the population is projected to have grown to

200,000 with further growth to 217,000 projected by 2028 and 229,000 by 2038 (Greater London

Authority, 2017a). The projected number of households is 86,000 (Greater London Authority, 2017b).

The Census reported that a total of 15,802 people were carers, and this is projected to have grown to

17,000 in 2018 (see 3.1.2 for methodology). Table 3 shows the findings by hours of unpaid care

provided per week (ONS, 2011), with carers in Richmond upon Thames representing 8.5% of the

resident population.

The proportion of Richmond’s population providing unpaid carer (8.5%) is similar to the average for SW

London (8.4%) and London as a whole (8.5%), and lower than the average in England (10.2%).

However, generally a lower proportion of Richmond’s population provides over 19 hours of care per

week.

Table 3. Census 2011: Provision of unpaid care

| Informal Care | ||||

| Provides no unpaid care (%) | Provides 1 to 19 hours unpaid care a week (%) | Provides 20 to 49 hours unpaid care a week (%) | Provides 50 or more hours unpaid care a week (%) | |

| Names | 2011 | 2011 | 2011 | 2011 |

| Croydon | 90.73 | 6.07 | 1.31 | 1.89 |

| Kingston upon Thames | 91.70 | 5.83 | 1.01 | 1.47 |

| Merton | 91.82 | 5.27 | 1.21 | 1.70 |

| Richmond upon Thames | 91.55 | 6.32 | 0.86 | 1.27 |

| Sutton | 90.38 | 6.54 | 1.18 | 1.90 |

| Wandsworth | 93.49 | 4.28 | 0.94 | 1.30 |

| South West London | 91.63 | 5.66 | 1.10 | 1.61 |

| London | 91.56 | 5.33 | 1.29 | 1.83 |

| England | 89.76 | 6.51 | 1.36 | 2.37 |

Source: Census 2011

However, currently there are just 1,683 carers recorded in General Practice, despite the vast majority

(87.5%) of practices who responded to a 2018 survey stating that they ask patients if they are a carer

on the new patient registration form. Similarly, a limited number of the total carer population (1,800 adult

carers) are registered with the Carers Hub Service, and fewer than 300 carers assessments were

performed by Richmond Council, suggesting that health professionals and support services may not be

aware of the carer responsibilities and associated support needs of patients, and may not be identifying,

or recording and flagging carers correctly.

3.1.2 Characteristics of carers in Richmond upon Thames

By applying local prevalence rates from the 2011 Census to population projections (Greater London

Authority, 2017a) estimates of numbers of carers by gender and age group in 2018 have been

calculated. Note that these rough estimates do not take into consideration changes in the number of

people requiring care. It is estimated that:

- Of those who provide unpaid care in Richmond upon Thames, 58% are female.

- Of all care providers, 31% are aged between 25 and 49 years, 41% between 50 and 64 years, and 22% are aged over 65 years.

- Of those who provide more than 50 hours of care per week, 39% are older than 65 years.

- Six percent of carers are younger than 25 years

Figure 1. Age and gender distribution of carers in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames by number of hours of unpaid care (estimated)

Source: (Census 2011/GLA, 2017)

Young carers and carers transitioning into adulthood

The 2011 census identified that there are 864 carers in Richmond upon Thames aged younger than 24

years who provide unpaid family care, and as of 2018 this figure is estimated to be 970 (Greater London

Authority, 2017a). In September 2018 480 young carers were being supported by the Richmond Carers

Centre.

Based on information from the Richmond Carers Centre a greater proportion of young carers are from

BME ethnic groups than the average for all carers within the borough (29% of young carers compared

to 13% of all carers identified by the 2011 census).

The 2014 Richmond Young People’s Survey (emotional and wellbeing themed report, pages 2 and 4)

showed that 11% of pupils in year 5, 6 and 7, and 7% of pupils in year 8 and 10, reported that they care

for someone at home on a regular basis who is unable to care for themselves. Only 1% felt this often

stopped them from taking part in recreational activities, and 3% felt it sometimes stopped them.

Parent carers and sandwich carers

Applying national research (The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010a) to Richmond’s

population it is estimated that there is a total of 2,100 parent carers in the borough, making up around

13% of the carer population. Also, it is estimated that around 1,300 are caring for children with

disabilities and a further 800 are caring for adult children. However, in Richmond-upon-Thames, there

is a total of 4,469 school pupils who have special educational needs (DfE, 2018), although it is likely

that not all of these pupils will be receiving care from their parents, it is likely that most are, suggesting

a discrepancy between the number of parent carers identified, and the true total number of parent carers

in the borough.

The number of ‘sandwich carers’ (those looking after young children at the same time as caring for the

older generation) is rising due to the pressures of an ageing population, combined with people starting

families later, nationally The number of middle-aged (50-64) female carers has risen by 13%, to 1.2

million, in the last ten years – a sharper increase than the total carer number (11%) (Carers UK, 2014).

This disproportionately affects women, in Richmond-upon-Thames 23% of women aged 50 to 64 are

carers, compared to 13% of men (ONS, 2011).

Parent and sandwich carers are less likely to identify as carers and are more likely to be caring from a

distance. In Richmond upon Thames the peak age for caring is 50-64 years. 34% of carers are aged

between 25 and 49 years, and 38% between 50 and 64 years. However, whilst the 2011 Census shows

that 72% of carers are aged between 25 and 64, just 48% of carers registered with the Richmond Carers

Hub Service in April 2018 were aged between 19 and 64.

Care for older people

As noted earlier, the majority of carers provide care for older people. In 2018, it is projected that 15.3%

Richmond upon Thames residents are aged over 65 years, 6.8% are aged over 75 years and 2.2%

over 85 years (Greater London Authority, 2017a). A vast majority of older people (96.6% of residents

aged 65 years and over and 93.7% of those aged 75 years and over (ONS, 2011)) live in the community.

The percentage of people aged over 65 years in Richmond upon Thames is projected to increase to

19.4% in 2038 (Greater London Authority, 2017a).

Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Carers

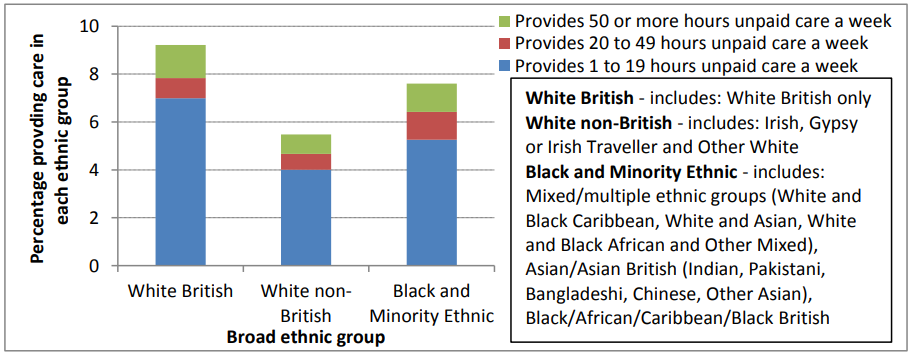

In Richmond, 2011 census data reveals that 14.1% of the population are from BAME groups, 14.5% of

the population belong to non-British White ethnic groups and the remaining 71.4% are White British.

The population of unpaid carers in Richmond has a similar ethnic composition although the proportion

of White British carers is higher than in the total population (77.9% compared to 71.4%). The proportion

of BAME and non-British White carers are both lower than the proportion of these ethnic groups within

the total population at 12.6% and 9.4% respectively.

Figure 2 below shows the percentage of unpaid carers by broad ethnic group for Richmond upon

Thames. The highest proportion of unpaid carers is seen in the White British ethnic group (12,316 (9%) providing care). The differences in unpaid care provision between the broader ethnic groups are similar

to the whole of England (Office for National Statistics, 2013b). However, as shown in Figure 3, some

differences are seen between individual ethnic groups that make up the three broader groups (White

British, White other and BAME), though it should be noted that numbers are small in some of these

groups.

Ethnic groups within the group White Other:

- Ethnic groups providing more care than the “White Other” average (5.5%): Irish (385

(8%) providing care) and Gypsy/Irish Traveller (White Other 19 (20%) providing care). - Ethnic groups providing similar care to the “White Other” average (5.5%): “Other

white (i.e. not Irish or Gypsy or Irish Traveller)” (1,084 (5%) providing care).

Ethnic groups within BAME:

- Ethnic groups providing more care than the BAME average (7.6%): Indian (559 (11%)

providing care), Pakistani (115 (10%) providing care), Bangladeshi (73 (8%) providing

care), and Other Asian (363 (8%) providing care). - Ethnic groups providing less care than the BAME average (7.6%): the four ethnic

groups in the Mixed/Multiple Ethnic Group (364 (5%) providing care) and “Chinese”

(107 (6%) providing care).

A total of 323 carers registered with the Richmond Carers Centre (RCC) identified themselves as

BAME. This is 17.39% of the total number of carers registered with the RCC, indicating a higher

proportion of BAME carers than is indicated by the 2011 census (12.6% of individuals who identified as

carers listed their ethnic group as BAME). RCC reports the actual number of BAME carers in the

borough is likely to be much higher, as many carers choose not to register with the Centre, do not

realise they are a carer, or actively seek support from the Council, local health services, or other groups.

Figure 2. Percentage of unpaid carers in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames by broad ethnic group (Census 2011)

Percentage of unpaid carers in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames by individual ethnic group

Source: (Census 2011/GLA, 2017)

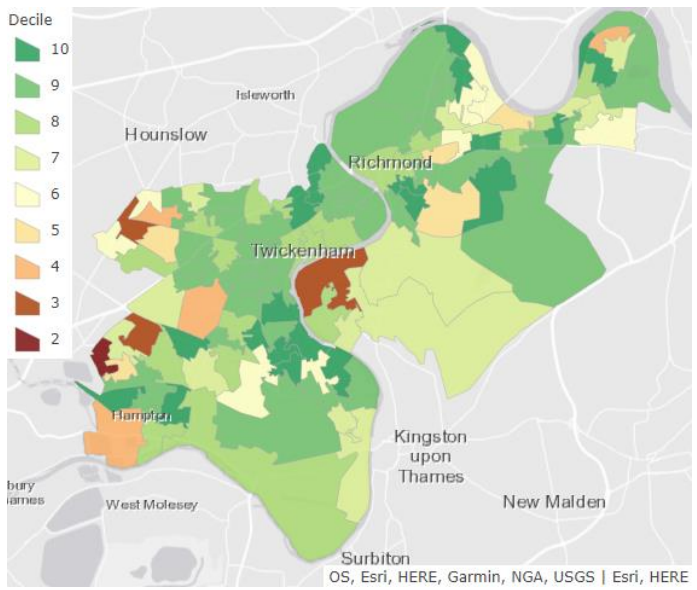

3.2 Deprivation

The percentage of residents who provide unpaid care in a certain region is associated with deprivation.

Consequently, given that Richmond upon Thames is one of the most affluent areas in the country, and

is the least deprived borough within London (as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015

(Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015)), it is no surprise that carer levels are lower

in the Borough as a whole.

However, as shown in the figure below it is important to recognise that pockets of high deprivation exist

within Hampton North; Heathfield; Ham, Petersham and Richmond Riverside; Barnes; Whitton;

Hampton; and West Twickenham and that level of carer need is likely to be higher in these more

deprived areas compared with more affluent areas. There are also families/individuals scattered

throughout other parts of the borough who are experiencing above average levels of deprivation and

are likely to have greater needs.

Figure 3. Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015 decile from 1 (most deprived) to 10 (least deprived) within the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

Source: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2015

3.3 Conditions of the people who are cared for

Nationally, according to the Survey of Carers in Households, the most common conditions amongst

people that are looked after by unpaid carers are: physical disability (58% of carers), sight or hearing

loss (20%), mental health problem (13%), learning disability (11%) and dementia (10%). The conditions

of people who are cared for often dictate the types and duration of caring activities that a carer

undertakes and understanding the prevalence of these conditions informs our knowledge of the health

needs of carers. This breakdown does not fully represent the care requirements of those cared for, as

autism spectrum disorder is included within the category of learning disability, despite those with autism

requiring significantly different care and support than others within this group. There is also no category

for those with multiple long-term conditions, who would be included in this data under the category of

their most debilitating condition.

The absence of a specific statistical breakdown for conditions such as autism, or for those with multiple

morbidities, has implications for local efforts to categorise these individuals and commissioning and

delivering services tailored to individuals with these conditions and their carers.

3.3.1 Physical disability

It is estimated that, in total (i.e. including those receiving unpaid help, those receiving paid help, and

those receiving no help), there are 12,582 Richmond upon Thames residents aged between 18 and 64

years with a physical disability, of which there are 2,862 with a serious disability (www.pansi.org.uk,

2016). This estimate is based on the prevalence data for moderate and serious disability by age and

sex included in the Health Survey for England (2001) applied to population projections from the Office

of National Statistics of the 18 to 64 population to give estimated numbers predicted to have a moderate

or serious physical disability.

3.3.2 Sensory impairment

In 2016/2017, there were 285 people registered as blind or severely sight impaired with Richmond

Council and 250 registered as partially sighted or sight impaired (NHS Digital, 2017a). In 2009/2010,

550 people who are deaf or hard of hearing were registered with Richmond Council (The Health and

Social Care Information Centre, 2010b).

3.3.3 Mental health problem

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) 2014 (NHS Digital, 2016) provides data on the

prevalence of both treated and untreated psychiatric disorders in the English adult population (aged 16 and over) by gender and age group. By applying the national prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders

from the APMS to the Richmond population (Greater London Authority, 2017a) and after adjusting for

age and sex, the number of people in Richmond upon Thames with these psychiatric disorders can be

estimated.

In total, it is estimated that 23,000 Richmond upon Thames residents aged 16-64 have a common

mental disorder (CMD), 6,400 screened positive for probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 800

had a psychotic disorder in the past year, 900 have autism, 3,000 have borderline personality disorder,

and 3,000 have bipolar disorder. In the age group 18-64, there are an estimated 4,000 Richmond upon

Thames residents with antisocial personality disorder.

In the population aged over 65 in Richmond upon Thames, it is estimated that there are 2,793 people

with depression and 875 with severe depression, with these numbers projected to increase by 19% and

24% respectively from 2017 to 2025. Prevalence rates from the Medical Research Council Cognitive

Function Ageing Study (McDougall et al. 2007) have been applied to population projections from the

Office of National Statistics of the 65 and over population to give estimated numbers predicted to have

depression, to 2025 (www.poppi.org.uk, 2016).

3.3.4 Learning disabilities

Applying national prevalence estimates to the Richmond upon Thames population, it is estimated that

3,683 adults have a learning disability. Of these, 789 adults are estimated to have a moderate or severe

learning disability (www.pansi.org.uk, 2016).

There are 445 (2.96/1000) adults with a learning disability getting long term support from Local

Authorities in Richmond upon Thames (NHS Digital, 2017b). This is higher than the London average

rate (2.77/1000) but lower than England’s (3.33/1000). In April 2015 Richmond Social Services records

indicated that 246 individuals with a learning disability were in receipt of formal community or institutionbased care. The disparity between this figure and the estimate that 3,683 adults in Richmond upon Thames have a learning disability, suggests that there are a large number of people not currently in

receipt of services, who are likely reliant upon friends and family for care and support.

One of the key findings of the Richmond upon Thames Learning Disabilities JSNA 2012/13 was that

carers are crucial in supporting the health needs of people with learning disabilities. The Learning

Disabilities JSNA included a community engagement process, for which 400 questionnaires were

distributed to adults with learning disabilities. The 280 questionnaires that were returned showed that

almost all respondents have a paid or unpaid carer (92%). The majority (70%) rely on paid carers but a

significant number (22%) rely on friends and family. More than half (52%) of respondents live in a

residential home and only 12% live alone. The remaining respondents live with friends (9%) and family

(27%).

3.3.5 Dementia

Applying national prevalence rates from the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study II (Matthews et al,

2013) to population projections (Greater London Authority, 2017a) and adjusting for age and sex, it is

estimated that there are 2,000 people with dementia in Richmond upon Thames. The number of people

with dementia is expected to increase because of the ageing of the population: using the same sources,

it is estimated that the number of people with dementia in Richmond will be 2,700 in 2028 – an increase

of 35%. However, BME groups are projected a seven-fold rise in the prevalence of dementia as the population ages, in comparison to a two-fold rise in the population as a whole. This will have implications

for future health and social care services, as well as for BME families and carers of those suffering from

dementia (LBRuT, BME Needs Assessment, 2017). It is estimated that two thirds of people with dementia live in private households in the community (applying these national figures to the population of Richmond upon Thames results in an estimated 1,700 people with dementia living in the community,

(Knapp et al., 2007) and that one third of people with dementia who live in the community are living

alone (applying these research findings to the population of Richmond upon Thames results in an

estimated 440 people with dementia living alone) (Mirando-Costillo, 2010).The majority of care for

people with dementia is provided by family members, and the demands of caring can have profound

negative effects on their social and emotional wellbeing (Brodaty, H, 2009).

4. Health, social and economic impact of caring

4.1 Health needs of carers

Research and analysis local data has found that carers are more likely to report health problems

compared to those who do not provide care.

Nationally, the 2018 State of Caring Report found that 72% of respondents suffered mental ill health,

and 61% suffered physical ill health as a result of caring. However 23% of carers reported refusing

health and care support due to concerns over quality (Carers UK, 2018), which demonstrates a clear

need to provide high quality services that effectively meet the health needs of carers.

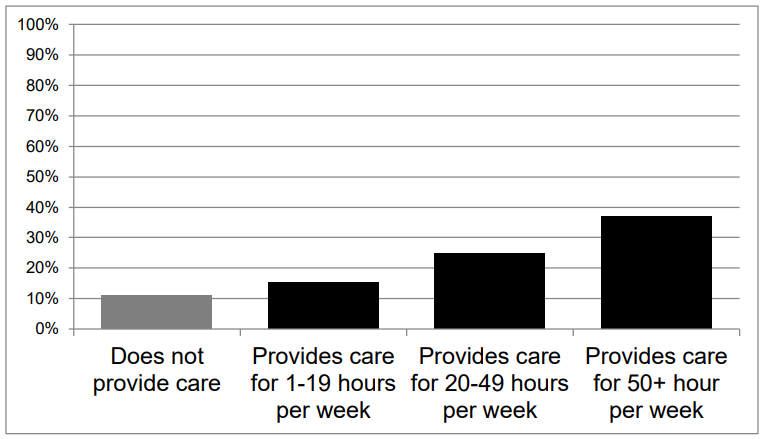

As shown in the analysis of Richmond’s 2011 Census data in the figure below, 20% of carers report

their health is poor (this is reflected in the 20.74% of carers registered with RCC who have reported

having their own physical or sensory disability or long-term condition (as at end April 2018)), compared

to 11% of those who do not provide care. This risk of poor health increases with the number of hours

of unpaid care that are provided.

The risk of poor health also increases with age, in Richmond upon Thames 67.4% of carers aged 65

and over reported having at least one long-term health condition compared to 53.3% of carers aged 18

to 64 (Survey of Adult Carers in England, 2016/17).

Compared to other South London Boroughs, carers in Richmond are more likely to have had to see a

GP for health issues relating to their caring duties in the past 12 months (33.9% in Richmond upon

Thames, compared to 27.8% Kingston upon Thames, 32.3% Merton, 31.4% Sutton (Survey of Adult

Carers in England, 2016/17)). Just 8.1% of carers in Richmond reported that their caring responsibilities

had no effect on their health. This is slightly lower than other South London boroughs (average 10.5%

(Survey of Adult Carers in England 2016/17)).

Figure 4. The proportion of the population of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames that reported their health was not good, for those who provide care (black) and those who do not provide care (grey).

Source: Census 2011

Pinquart and Sorensen (2007) undertook an analysis of research studies on carer health and found the

following possible reasons for the poorer health of carers:

- A large proportion of carers are aged over 65 years, particularly those who provide more than 50 hours of care a week, who are at higher risk of poor health.

- Caring is associated with poorer health-related behaviour – carers have a poorer diet and exercise less.

- Caring can result in high levels of psychological distress and can be physically tiring, resulting in a reduced immune system and a higher susceptibility to illness.

4.2 Social isolation and social cohesion

Research also suggests that being a carer can influence the ability to participate in social activities.

Carers are at risk of social isolation (Brodaty, 2009), particularly carers aged 65 years and over. In

Richmond-upon-Thames just 29.7% of carers aged 65 and over report having as much social contact

as they want, compared to 36.3% of carers aged 18 to 64 (Survey of Adult Carers in England, 2016/17).

This may have negative consequences for their physical and mental health (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2007). Nationally, 16.2% of carers reported they have little social contact and feel socially isolated, the

average across South London is 16.6% and in Richmond the figure is comparatively slightly lower at

15.8% (Survey of adult Carers in England, 2016/17).

‘Social cohesion’ refers to the strength of community relationships and levels of participation in

community activities and public affairs. It also refers to social contacts and networks (with family, friends

and relatives), social support and a sense of belonging. Evidence shows that higher levels of ‘social

cohesion’ are associated with better levels of health including mental health and wellbeing, as well as

other social and economic benefits (Wilkinson, 1996). This can be particularly important for carers who

are at risk of social isolation.

In Richmond, the results from Public Attitude Survey (MOPAC, 2018) suggest that overall levels of

social cohesion are high compared to other parts of London. For example, 97% of residents agree that

Richmond is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together, which is the second

highest proportion in London.

4.3 Employment of carers

Work has an important role in promoting and protecting mental wellbeing. It is an important determinant

of self-esteem and identity. It also provides a sense of fulfilment and opportunities for social interaction,

and income.

However, without adequate support working and caring together can have a considerable detrimental

impact on a carer’s health and wellbeing. Carers working full-time and providing 50 hours or more

unpaid care per week are 2.4 times (men) and 2.7 times (women) more likely to report their health as

‘not good’ (ONS, 2011).

While approximately half of the carers who provide more than 20 hours of care a week are also in paid

employment (ONS, 2011), providing care is often a reason for not working or for working part-time,

particularly for female carers (Beesley, 2006). 35% of respondents to the 2018 State of Caring Survey

reported giving up work to provide care, with a further 16% saying they had reduced their hours of work

in order to support the person they care for (Carers UK, 2018). In addition, it may be more difficult to

return to work for carers after a period of unemployment.

According to the national Survey of Carers in Households, in those aged under 70 years, 26% reported

that their ability to take up or stay in employment had been affected because of caring, whereas 74%

did not feel this was the case. Among those whose employment had been affected 39% left

employment, 32% reduced employment hours and 18% agreed flexible employment (respondents

could select more than one option).

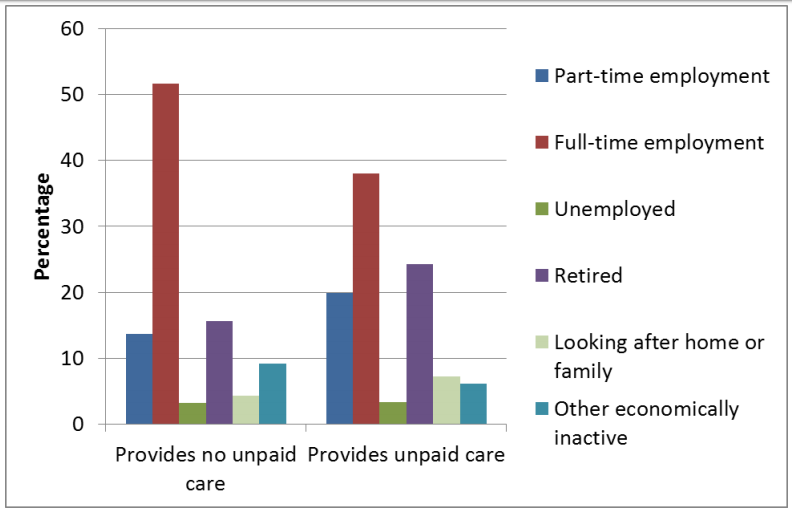

In Richmond, as shown in the figure below, men and women who provide care are less likely to be in

full-time employment (38% compared to 52% of those who do not provide care) and more likely to be

in part-time employment (20% compared to 14% of those who do not provide unpaid care) (ONS, 2011).

The Survey of Adult Carers in England 2016/17 shows a high proportion of carers in Richmond who

describe themselves as retired (60.1%). This figure is higher than the 50.8% average across South

London, and both figures are considerably higher than the proportion of unpaid carers who are identified

as retired in the 2011 Census (24%). The Survey of Adult Carers in England is based on data around

carers who are in receipt of support services or known to local authorities. This therefore suggests that

retired carers are much more likely to access services or be known to local authorities than non-retired

carers.

Figure 5. Economic activity of those aged 16 years and over in the London Borough of

Richmond upon Thames

Source: Census 2011

Further analysis of Richmond Census data also shows that the employment impact of being a carer

differs for men and women, with 12% of male carers in part-time employment compared to 26% of

female.

Also, the proportion of men and women who are working full time decreases with the number of hours

of care that are provided, while the proportion of people who are economically inactive because they

are looking after family or are retired increases with the number of care hours.

Measuring the economic consequences of caring is difficult, and estimates vary widely. However,

estimates can be made. For instance, Casey (2011) estimated the total economic value to be £1.0

billion based on minimum hourly wage rates; and Beasley (2006) estimated the full economic cost to

be £9.4 billion when consideration of direct expenditure, foregone waged and non-waged time, and

career prospects and accommodation income suggests that the cost of caring for those aged 65 years

and over was also included.

4.4 Education and wellbeing of young carers

Many young carers take on their role because of multiple care needs in the family, and it is becoming

increasingly common to find multiple caring families. Growing up in an environment such as this, young

carers mature quickly and gain practical skills that aid independence. However, national research show

that caring can have an adverse impact on educational attendance or attainment, physical and

emotional health, social activities and aspirations (Chris Dearden and Saul Becker, 2000; Fiona Becker

and Saul Becker, 2008, Department for Health, 2017). For young adult carers, care responsibilities may

delay moving out or away from home and decrease employment possibilities or ability to pursue further

education (Chris Dearden and Saul Becker, 2000; Fiona Becker and Saul Becker, 2008).

Transition arrangements are therefore crucial to minimising the negative impact that caring can have

on a young person’s employment or higher education opportunities as they get older.

Young & young adult carers risk being hidden and not receiving appropriate support. Young carers

remain hidden for many reasons including:

- They do not realise they are a carer or that their life is different to their peers

- Their parents do not realise that their children are carers

- They don’t want to be different from their peers

- They worry that the family will be split up and taken into care

- Their parent’s condition is not obvious, so people don’t think that they need any help

- There has been no opportunity to share their story

- They see no reason or positive actions occurring as a result of telling their story.

It has been well evidenced in research that young carers experience heightened levels of bullying.

Recent research by the University of Nottingham and Carers Trust found that a quarter (26%) of

young carers surveyed were bullied at school specifically because of their caring role (Carers Trust,

2016).

The experiences of LGBT young adult carers can be even more challenging. Research by the Carers

Trust indicates that LGBT young adult carers are three times more likely to experience bullying than

young adult carers and are more than three times more likely to have a mental health problem than

their peers (Carers Trust, 2016).

5. Stakeholder views

A collection of local consultation exercises with carers, carers organizations, statutory bodies and other

partner organizations included the following:

- Consultation of carers in relation to the Out of Hospital Strategy and involved in the

development of new or re-designed services - A Carers’ Strategy Workshop

- A Carers Survey, required by the Department of Health, with 447 carers (response rate 52%)

- Questions included in the Adults Social Care Outcomes Framework

Full details of the findings are included in the 2013 to 2015 Carers Strategy. The key themes that emerged from the engagement included:

- Terminology – Many carers consider themselves to be a husband/wife/partner/friend mother/father/sister/brother/son or daughter and don’t think of themselves as a ‘carer’.

- Information and advice – Although the Adults Social Care Outcomes Framework shows that almost three quarters of carers in Richmond upon Thames finds it easy to find information about services, there is a need for information to easily accessible and up to date.

- Health and wellbeing – The importance of respite care and breaks for carers, and the role of the GP in identifying carers and signposting them to existing services.

- Carers as expert partners in care – Recognizing the carers’ views and involving carers in care decisions and plans, and understanding their role as advocate for those they care for.

- Transitions – the impact of service transitions (e.g. hospital discharges), and the transitions young carers face when becoming an adult carer or moving away from home, can be considerable upon a carers health and wellbeing, therefore services should endeavour to implement pathways to improve this.

6. Carer services in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

Services in the borough are listed on the CarePlace website.

Services for carers currently funded by the Richmond Council and/or Richmond Clinical Commissioning

Group include:

- The Carers Hub Service: this Local Authority funded service provides universal and specialist information and advice services, informal individual and group emotional support, a caring café for carers and people they care for living with dementia, a dedicated young carers service, training and learning opportunities for adult carers, opportunities for carer engagement, carer awareness training for professionals and strategic leadership. Services are provided by a group of 6 charities working together: Richmond Carers Centre (lead), Addiction Support and Care Agency, SW London Alzheimer’s Society (Richmond), Crossroads Care Richmond and Kingston, Richmond Borough Mind (Carers in Mind) and Integrated Neurological Services

- Carers assessments: these give carers the opportunity to discuss the physical, emotional and practical impact of caring on their life and enables social care practitioners to direct them to services which can support them. For adult carers, assessments are delivered by the Richmond Adult Social Services Directorate. The Directorate is currently implementing an improvement plan to ensure carers understand the assessment process and potential outcomes.

- Carers Emergency Card: available to carers who have had a carer’s assessment and enables access to emergency respite if the carer is suddenly unable to provide care due to accident or other exceptional circumstances.

- Shared Lives dementia scheme: this Council funded scheme helps carers of people with dementia, by providing a Shared Lives Carer to look after the person they care for.

- Telecare/Careline and emergency alarms: 24-hour emergency monitoring systems that can help older and vulnerable people to remain living independently and safely in their own homes, giving peace of mind to carers who do not live with the person they look after, the telecare service is delivered by the Council, following an assessment.

- Children’s services: single point of access (SPA): the SPA acts as a single gateway for all incoming contacts into the Richmond-upon-Thames Children’s Services (Achieving for Children), providing telephone and web-based support to professionals, children, young people and parents. Children’s Services refer adults for a self-directed support assessment where young people are identified as providing a caring role to an adult with disabilities or a long-term condition. Young carers identified by Adult Services are referred to Children’s Services for appropriate assessment and support.

- Seasonal flu vaccination: Carers are eligible for free seasonal flu vaccination. This is a service delivered by local health partners including GP surgeries, and some local pharmacies.

Also, a range of universal services are available to improve the health and wellbeing of Richmond upon Thames residents. These services can also benefit carers. They include:

- The Richmond Wellbeing Service, a service for local people who experience common mental health problems, such as depression or anxiety.

- Free NHS Health Checks for people aged between 40 and 74 years.

- Community Independent Living Service (CILS), a network of support, information, advice and signposting services for vulnerable adults. The aim of the service is to help people to live as independently as possible within the community.

- Transport services such as the Super Shopper Bus, which provides accessible buses to run fortnightly trips to supermarkets.

- The Expert Patients Programme, a self-care programme which is free for people and carers living with long-term health conditions.

Since 2014 the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and Richmond CCG have adopted an Outcome Based Commissioning Model, so that community services are oriented towards delivering outcomes that matter for patients and service users. Therefore, a set of outcomes for carers have been developed through consultation with local stakeholders and carers groups, the overarching theme across all groups and populations was the need for consistent, joined-up care across services and for service users and carers to know whom to turn to when they needed help. Three carer specific outcomes have been produced. Attached to each outcome are a number of outcome goals to demonstrate specific goals that services can achieve. The goals against the first outcome have been adapted by the Richmond Carers Centre and made more specific about what a good experience may feel like:

| Carers Specific Outcomes | Outcome goals |

| I want to have a good experience of care and support |

Recognised as playing an important part in the wellbeing of the person they care for |

| Treated with respect and dignity | |

| Help to make the process of caring as smooth as possible | |

| I need help reducing the stress of caring |

I know where to look for support (including peer support, training and advice) when I need it and get it |

| I know my own health is valued | |

| I want to feel involved and listened to (consulted in decisions regarding the cared for) |

|

| I want to have a break from caring when I need to | |

| I want support to live a normal life |

I have been recognised as a carer and offered sufficient support to live my own life as well as care |

| I have a good quality of life | |

| I don’t feel isolated as a carer |

Respondents to the 2016/17 Survey of Adult Carers in England indicate that 63.6% of carers who have

received support from Social Services with the past 12 months in Richmond are satisfied with the

support they have received. This is lower than both the South London average (65.7%) and the national

average (71%).

7. Identification of carers & service uptake

The number of carers in Richmond reported in the 2011 Census (15,802; 8.5%) is much higher than

the number of carers that have been identified by services and utilize key carer specific and openaccess services for residents.

For instance, as show in the table below, in general practice (l1,683), in the voluntary sector (around

1,800 adult carers identified by the Carers Hub Service) and by social care (298 adult carers had a

carers assessment in 2016/17).

Table 4. Identification of carers in general practice, community health services and

mental health services

| Number of adult carers reported: |

Number of young carers reported: |

|

| Carers reported in the 2011 Census |

14,938 carers aged over 25 years | 864 carers aged below 25 years. |

| Services for carers | ||

| Carers Hub Service | Over 1800 adult carers (June 2018) |

480 young carers (August 2018) |

| Carers Assessment | During 2016/17 298 adult carers received a carer’s assessment |

N/A |

| South West London St George’s Trust |

Unknown | |

| Carer’s Payments | During 2016/17 27 adult carers received a carer’s break payment |

N/A |

| Children’s services: single point of access (SPA) |

N/A | Young carers are not recorded through the Single Point of Access system, and are only recorded if they access the Carers Hub Service (see above) |

| General Practice | 1,683 carers identified by 16 GP practices (of a total of 28) |

|

| Health and wellbeing services for all Richmond residents | ||

| Health check | Unknown | Unknown |

| Richmond Wellbeing service | Unknown | Unknown |

| Community Independent Living Service |

Unknown | n/a |

1. Not reported separately for adult carers and young carers

Carers assessments

The number of carer assessments undertaken by the London Borough of Richmond-upon-Thames

Adult Social Services directorate is significantly reduced for 2016/17 from previous years. This reduction

can be attributed in part to procedural changes relating to the removal of incentives for completing a carers assessment and in part to systems issues whereby the recording of holistic assessments conducted for carer and cared for together is not synchronised with the recording of carers assessments.

A programme of work to review the carers assessment process is being undertaken and actions relating

to this programme of work could include the following:

- Introducing surgeries for carer assessment at the carer’s centre and other venues.

- Articulating the local carer’s offer which sets out the benefits of assessment and the local services available to carers following an assessment.

- Putting in place a staff programme of training and support so they are aware of the benefit of assessment.

- Developing carers champions in each team and linking them to carers through the carer’s centre.

Single Point of Access Scheme

All young people who receive an early help assessment via the Single Point of Access scheme will be

assessed holistically with their family and identified as a young carer if appropriate. These young carers

are then referred to the Carers Hub Service/Richmond Carers Centre to receive the appropriate support.

Current recording mechanisms are not synchronised and fail to indicate the total number of young

people who are identified as young carers by the SPA scheme, therefore a review of the systems and

pathways for young carers is being conducted to improve recording, update the pathway if necessary

and upskill the workforce to improve the identification of young carers.

8. National carer benefits

8.1 Impact of Welfare Reforms on carers

The main changes to the welfare system affecting carers are:

- Universal credit – this single benefit replaces previous benefits and tax credits for people of working age including working tax credit, child tax credit, housing benefit, council tax benefit, income support, income-based jobseeker’s allowance, income-based employment and support allowance.

- Personal Independence Payment – this has replaced Disability Living Allowance from April 2013. Since the announcement of reductions in spending on Disability Living Allowance/Personal Independence Payment in 2010, estimated figures show that the change would entail a 6.6% reduction in the number of people in payment of Carer’s Allowance in this group, Carers UK has raised concerns that this will have a considerable negative impact considering the implications of an ageing population, and people living longer with disabilities, causing the number of people needing Carer’s Allowance to rise by an average of 21,000 since 2003 (Carers UK, 2013).

9. Conclusions

National profile

- The vast majority of care is provided by family, friends and relatives, who make up the 5.8 million carers in England and Wales (ONS, 2011)

- The number of unpaid carers is expected to increase in the future because of demographic change and changes in community care policy (Pickard, 2008; Carers UK, 2001), nationally it is expected that by 2031 3 in 5 people will become carers at some point in their lives (Carers UK, 2015).

- Women are slightly more likely to provide care than men.

- The peak age for caring is 50-64 years.

- The following groups of carers can be identified: young carers and young adult carers, caring for a parent or sibling; parent carers caring for a child, carers of older people, mostly middleaged children or older aged spouses, and; ‘sandwich’ carers, who care for a parent or elder and child simultaneously

- The proportion of carers varies among ethnic groups.

- Regions with a higher proportion of people with disability, a higher proportion of older people,

and a higher level of deprivation typically have a higher proportion of unpaid carers. - Most carers (40%) care for their parents or parents-in-law, and over a quarter (26%) care for

their spouse or partner. - Most frequently cited reasons for caring are: physical disability (58% of carers), long-standing illness (37%), sight or hearing loss (20%), problems connected to ageing (17%), mental health problem (13%), a learning disability (11%) and dementia (10%).

Richmond upon Thames profile

- There are 15,802 carers. This is 8.5% of all residents.

- The proportion of carers is lower than the England average (10.2%) and similar to London (8.5%).

- 59% of carers are female.

- 31% of carers are aged between 25 and 49 years, 41% between 50 and 64 years, and 22% are aged over 65 years. Six percent of carers are younger than 25 years (n=970).

- Three quarters of carers provide care for 1-19 hours a week.

- Richmond upon Thames is one of the most affluent areas in the country. However, there are pockets of high deprivation.

- The percentage of people aged over 65 years in Richmond upon Thames is projected to increase from 15.3% in 2018 to 19.4% in 2038 (Greater London Authority, 2017a), and the carer population is expected to increase to accommodate this.

Impact of caring

- Carers are more likely to report health problems: 20% of carers in Richmond upon Thames report their health is not good, compared to 11% of those who do not provide care.

- While 60% of carers in Richmond upon Thames are economically active, providing care is often a reason for not working or for working part-time. It may also be more difficult to return to work after a period of not working.

Stakeholder views

- Engagement with carers, carers organizations and others identified that: many carers do not consider themselves to be a carer; accessibility of information and advice is important; respite care and breaks for carers are important; and there is a need to recognize carers as an expert partner in care.

Services for carers

- Services that are currently available for carers include: the Carers Hub Service; Carers assessments; carers break payments; carers emergency card; shared lives dementia scheme and telecare/careline and emergency alarms. Carers are eligible for a free flu jab.

- A range of universal services are available to improve the health and wellbeing of Richmond upon Thames residents, including carers, including NHS Health Checks.

- The number of carers reported in the 2011 Census (15,802; 8.5%) is much higher than the number of carers that have been identified in general practice (1,683 in September 2018), in the voluntary sector (around 1,800 adult carers identified by the Carers Hub Service, and around 370 by Richmond Borough Mind “Carers in Mind”) and by social care (298 adult carers had carers assessments in 2016/17).

10. Gaps and Challenges

The findings from this needs assessment will provide information to support the development of the

Richmond Carers Strategy. Key recommendations that will be outlined in more detail in the Strategy

include:

Gaps in local knowledge and understanding of carers

- Supporting carers to understand assessment process and understanding how to manage expectations and satisfaction with the process

- Number of carers of people living with autism and their needs

- Number of carers of people living with co-morbidities and their needs

- Understanding needs and supporting carers in employment

- Number of Sandwich Carers and their needs

- Number of young carers and their needs

- Access of carers to universal services that can support their health and well-being e.g. NHS health checks

- Up-to-date figures on carers assessments completed

Challenges in local provision and delivery of services

- Developing integrated services and systems that work for carers

-

- Carer assessments – Having identified issues around the carer assessment process as a key barrier to ensuring carers are able to easily move between services to receive the support they need, an improvement plan will be enacted to increase the number of carers being assessed, address key requirements and expectations around recording carers assessments and deliver training in best practice and the legal requirements relating to carer assessments.

- Young carer assessments – Current recording mechanisms are not synchronised and fail to indicate the total number of young people who are identified as young carers by the SPA scheme, therefore a review of the systems and pathways for young carers is being conducted to improve recording, update the pathway if necessary and upskill the workforce to improve the identification of young carers.

- Improving the identification of carers

- Supporting young carers

- Providing relevant advice, information and support

- Recognising and supporting carers in the wider community

- Improving carers health and wellbeing

11. References

Beesley, L. (2006). Informal Care in England, Wanless social care review. King’s Fund.

Brodaty, H. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience; 11(2): 217–228.

Cabinet Office. (2006). Reaching Out: An Action Plan on Social Exclusion.

Carers Trust. (2016). Young people caring OUT there: experiences of LGBT young adult carers in Scotland.

Carers UK, the University of Sheffield and the University of Leeds. (2015). Valuing Carers 2015: the rising value of carers’ support.

Carers UK. (2006a). Caring for sick or disabled children.

Carers UK. (2012a). Facts about Carers.

Carers UK. (2011). Half a million voices.

Carers UK. (2001). It Could Be You – A report on the chances of becoming a carer.

Carers UK. (2006b). Managing more than most: A statistical analysis of families with sick or disabled children.

Carers UK. (2012b). Sandwich caring.

Carers UK. (2013). Update: Impact of Personal Independence implementation on Carer’s Allowance.

Carers UK. (2014). Sandwich generation is growing concern. Access online.

Carers UK, (2017). The State of Caring 2017.

Carers UK. (2018). The State of Caring 2018.

Casey, B. (2011). The Value and Costs of Informal care.

Census. (2011).

Chris Dearden and Saul Becker. (2000). Growing up caring: Vulnerability and transition to adulthood –

young carers’ experiences. Joseph Rowntree Foundation; National Youth Agency.

Cross-Government publication. (2010). Recognised, valued and supported: next steps for the Carers

Strategy.

DataRich. (2011).

Datarich. (2012/13).

Department for Communities and Local Government. (2015). English Indices of Deprivation 2015.

Department for Education. (2017). The Lives of Young Carers in England.

Department for Education. (2018). Special Educational Needs in England: January 2018.

Department of Health. (2009). Living Well with Dementia: a National Dementia Strategy.

Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2010). How fair is Britain? Equality, Human Rights and Good Relations in 2010 – The First Triennial Review.

Health & Social Care Information Centre. (2010). Survey of Carers in Households – England, 2009-10.

Ipsos MORI. (2008). Assessing Richmond upon Thames’ performance: Results of the Place Survey

2008/09 for the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and partners.

Greater London Authority. (2017a). 2016-based population projections: Central Trend-based projection (using a 10-year migration scenario)

Greater London Authority. (2017b). 2016-based central trend household projection. Borough-level.

Knapp et al. (2007) Dementia UK: Report to the Alzheimer’s Society Kings College London and

London School of Economics and Political Science.

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. (2011/2012). Annual Public Health Report.

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. (2013a). Joint Strategic Needs Assessment: Mental health and wellbeing.

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. (2013b). Learning Disability Service Users Equalities Profile 2012/13

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. (2017). BME Older People Needs Assessment.

Matthews et al. (2013). A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II.

Mirando-Costillo, C., Woods, B. & Orrell, M. (2010). People with dementia living alone: what are their

needs and what kind of support are they receiving? International Psychogeriatrics, 22, 4, 607-617

NHS Digital. (2016). Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014.

NHS Digital. (2017a). Registered Blind and Partially Sighted People, England 2016-17.

NHS Digital. (2017b). Adult social care activity and finance report, Short and Long Term Care

statistics.

NHS Digital (2017c). Survey of Adult Carers in England, 2017-17.

NHS Richmond CCG. (2018). Identification of carers in GP practices

England and NHS South of England. (2012). Dementia Prevalence Calculator.

NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care . (2010). Survey of Carers in Households 2009/10.

Office for National Statistics. (2013c). 2011 Census Analysis: Unpaid care in England and Wales, 2011 and comparison with 2001.

Office for National Statistics. (2013b). Ethnic Variations in General Health and Unpaid Care Provision 2011.

Office for National Statistics. (2013a). Full story: The gender gap in unpaid care provision: is there an impact on health and economic position?

Office for National Statistics. (2012). Subnational Population Projections, 2010-based projections.

Pickard, L. (2008). Informal Care for Older People Provided by Their Adult Children: Projections of Supply and Demand to 2041 in England. Personal Social Services Research Unit.

Pinquart, M., & Sorensen, S. (2007). Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A MetaAnalysis. Journal of Gertontology, volume 62B, number 2, page 126-137.

Public Health England. (2013). Learning Disabilities Profile 2013 Richmond upon Thames.

The Health and Social Care Information Centre. (2010b). People registered as deaf or hard of hearing, year endeing 31 March 2010.

Wilkinson, R. (1996). Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge.

Document Information

Commissioning and Quality Standards Division,

Adult Social Services

Authors: Juliana Braithwaite, Katie Harrison, Steve Shaffelburg

Date of publication: February 2019

Date of refresh: February 2022

Acknowledgements

Richard Wiles, Head of Commissioning Public Health, Wellbeing and Service Development, London

Borough of Richmond upon Thames

Caroline O’Neill, Senior Engagement Manager, Richmond Clinical Commissioning Group

Sarah Reid, Head of Children, Youth and Partnerships, Achieving for Children

John Street, Head of Community Services, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

Melissa Wilks, CEO, Richmond Carers Centre

Steve Bow, Business Intelligence Manager, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

Andre Modlitba, Analyst Support Officer, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames

Shannon Katiyo, Consultant in Public Health – Adults, Social Care and Health Care, London Borough

of Richmond upon Thames

Members of the Richmond Carers Strategy Reference Group.