1 Introduction

Excess weight is a major public health issue that presents significant health risk and affects children, adolescents and adults.[1] The main purpose of this health needs assessment is to better understand the prevalence of excess weight, describe the school measurement programme and its importance for measuring and tackling obesity in children, describe the services available to children, and to use our better understanding to consider and make recommendations about ways to help children maintain or reach a healthier weight in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.

It is presented in four sections, background, local picture, conclusion and recommendations. The background section provides information helpful to understanding the issues. It includes national statistics and the characteristics of interventions that reduce obesity. The local picture section presents all the local data and considers local service provision. A conclusion is then drawn and recommendations made based on a consideration of the findings and what can be achieved locally.

2 Background

2.1. Definition of excess weight

A child’s BMI is calculated in the same way as an adult. This is then plotted against their age and sex onto the UK 1990 growth chart. This process produces a BMI centile, if a child’s centile is equal to or greater than 91 their weight status is classified as overweight, if it is equal to or greater than 98 they are classified as clinically obese.

In this report a second set of surveillance thresholds are used to define overweight and obesity in children. These are thresholds routinely used by the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP), Health Survey for England (HSE) and in service planning. These thresholds are slightly lower and classify children between the 85th and 95th centiles as overweight and those over the 95th centile as obese.[2] Where the term ‘excess weight’ is used in this report, it refers to children with a BMI centile of 85 or above.

2.2. Risk factors for excess weight in children

Similar to adults, at its simplest excess weight in children is caused by an energy imbalance. Children in the UK have diets high in energy dense foods, saturated fat and non-milk extrinsic sugars, but low in fibre, fruits and vegetables, and this is even more evident in children from lower income and one-parent families. [3] Those that eat high calorie diets and do not do sufficient physical activity will gain weight. However, as with adults, the story of obesity in children is a complex one.

The recent rise in obesity in children cannot be attributed to genetic factors alone. Societal, physical, and environmental factors have a role. The impact of societal and environmental factors can be seen in the national child obesity measurement programme data which shows differences in obesity levels in different environments. For example, it consistently found that obesity prevalence was significantly higher in urban areas compared to rural areas. The prevalence of childhood obesity has been linked with household income, parental BMI, child gender and physical activity level.

The social environment also has a profound impact on obestity. The role of the parent or carer is very important. A child that has at least one obese parent is around three times more likely to be obese than a child without an obese parent.[4] The government recommends that to reduce obesity in children it is vital to work with parents and advocates taking a whole-family approach. See Healthy weight, Healthy Lives: A Cross-Government Strategy for England (Cross-Government Obesity Unit 2008).

The 2011 report Childhood Obesity in London contains a wealth of useful information. It notes that children do have a good awareness of what foods are healthy and can identify the consequences of not eating healthily however they do not see it as their role to be interested in health and do not see messages about their future health as personally relevant.[5] It also reports work by Kipping et al which found that the key common modifiable risk factors of obesity include high levels of television viewing, low levels of physical activity, parental inactivity, and high levels of consumption of dietary fat, carbohydrate and sweetened drinks.[6]

2.3. The consequences of excess weight in childhood

In childhood, obesity is associated with a number of health risks including psychological issues such as low self esteem, eating disorders, musculoskeletal problems, respiratory problems and type 2 diabetes. A crucial public health consideration is that Individuals who are obese as children are more likely to be obese in adulthood. Being obese in childhood increases the risk of poor health and mortality in adulthood.

In children and adolescents the associated morbidities include hypertension, hyperinsulinaemia, dyslipidaemia, type 2 diabetes, psychosocial dysfunction, and exacerbation of existing conditions such as asthma. Excess weight also has a significant impact on psychological wellbeing, with many children developing negative self image and low self esteem issues.[7]

Bullying and social exclusion can be a consequence of excess weight. This was clearly highlighted in the recent findings of the Richmond Young People’s survey 2012, where bullying was related towards peer attitudes of weight and dieting.[8] The Survey also highlighted that girls in particular are concerned about their weight at an early age with 42% of 11-12 year olds stating that they would like to lose weight. At age 14-15 years, 59% of girls said they would like to lose weight.

2.4. Costs

The costs of childhood obesity have been estimated for the report Childhood Obesity in London[9]. It notes that the direct costs of childhood obesity are low but because obese children tend to become obese adults the future costs are much higher. It summarised that an obese child in London is likely to cost around £31 a year in direct costs which could rise to a total (direct and indirect) cost of £611 a year if they continue to be obese in adulthood.

2.5. National Statistics

In England, the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) measures the weight and height of children within state maintained primary schools in reception class (aged 4 to 5 years) and year 6 (aged 10 to 11 years). Their figures are based on very large numbers of measurements and provide a robust assessment of obesity in children. The Public Health England website (https://www.noo.org.uk/NCMP) describes the programme in detail.

In 2012/13 the National Child Measurement Programme found that 22.3% of Reception aged children and 33.3% of Year 6 children were either overweight or obese. Although levels of overweight were similar in reception year (13%) and year 6 (14.4%), the number of obese children was double in year 6 (18.7%) compared to those in reception year (9.3%).

Patterns of excess weight gain are broadly similar in girls and boys (Table 1). In 2012/13 boys 23.2% are overweight or obese in Reception year, which increases to 34.8% by Year 6. In girls, 21.3% are overweight or obese in Reception, which increases to 31.8% by Year 6. Looking at obesity alone 9.7% of boys in Reception year are obese and this increases to 20.4% by year six. Whilst in girls 8.8% are obese at Reception and by Year 6 this has doubled to 17.4%.

Table 1: Findings from the 2012/13 National Child Measurement Programme

|

|

Underweight % |

Healthy Weight % |

Overweight % |

Obese % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reception |

boys |

1.1 |

75.7 |

13.5 |

9.7 |

|

girls |

0.7 |

78.1 |

12.5 |

8.8 |

|

|

Year 6 |

boys |

1.1 |

64.1 |

14.4 |

20.4 |

|

girls |

1.5 |

66.7 |

14.4 |

17.4 |

|

The most recent national data shows a modest fall in the proportion of obese children in comparison to previous years. This is welcome but it is too early to establish if this is the start of a downward trend.

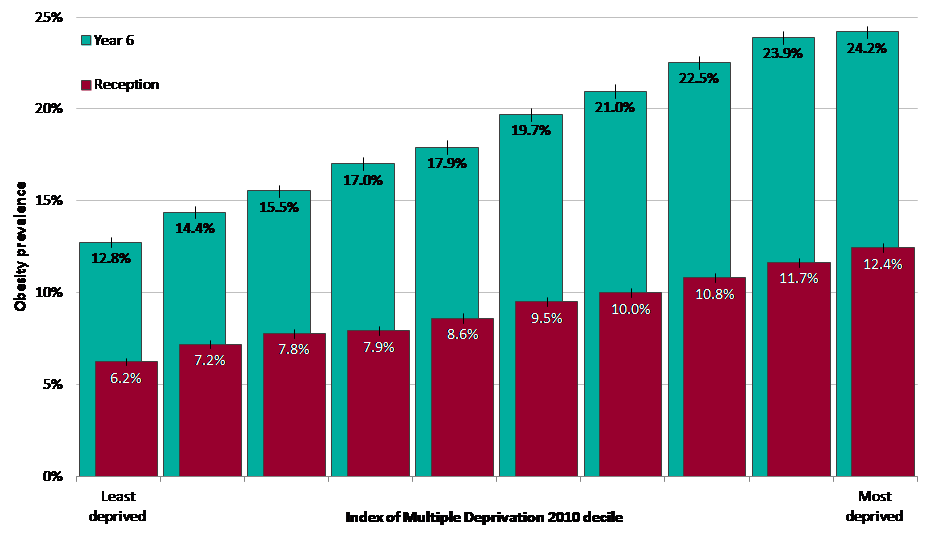

The national data show the correlation between social gradients and obesity prevalence is more pronounced in children than adults. In children the trend is striking, there is a steady increase in the prevalence of obesity from the bottom most deprived 10% of areas to the least deprived 10% of areas (Figure 1). In children living in the most deprived areas obesity prevalence is double that of children living in the least deprived areas.[10]

Figure 1: Obesity Prevalence by Deprivation deciles, 2012/13

Source: NOO, 2012

Data from the child measurement programme showed that obesity prevalence was significantly higher than the national average for children in both reception year and year 6 in the ethnic groups ‘Asian or Asian British’, ‘Any Other Ethnic Group’, ‘Black or Black British’ and for the ethnic group ‘Mixed’. It was found to be lower than the national average for children in the ‘White’ ethnic group; and for ‘Chinese’ in the Reception year. The authors of the 2012/13 data note that there are known associations between ethnicity and area deprivation. Deprived urban areas in England tend to also have a higher proportion of individuals from non-White ethnic groups, so it is likely that there are confounding factors which affect obesity prevalence by ethnic group.

2.6. Interventions

This section is a summary of findings from the Greater London Intelligence Unit Report Childhood Obesity in London. According to this report measures to address childhood obesity can be thought of as falling into three broad categories:

- “Weight management programmes” targeted at individuals who are already overweight or obese, with the intention of helping them reduce or manage their weight

- Preventative interventions

- Wider prevention activity, particularly focussing on environmental factors such as the built environment, availability of services, and food systems.

In reviewing the evidence the report concluded that community or school based programmes that are non-stigmatising can maintain child participation and achieve favourable outcomes. In addition, parents and carers have a very important influencing role in terms of diet and lifestyle and many of the best performing interventions involved both the child and parent. Early intervention is important for establishing healthy lifestyles and behaviours at an early age. It was found that programmes that promote a healthy lifestyle were more effective than those focussed only on weight and early prevention and intervention is more effective and less costly than treatment and other consequences of obesity later in life. Limiting television viewing and “screen time” was found to be effective in addressing sedentary lifestyles. The report argues for local childhood obesity interventions that are based on the evidence of effectiveness but notes the potential for unintended consequences that might occur as a result of a programme. Importantly, local interventions should include evaluation to allow analysis of what works well in the local population, and what is less effective.

2.6.1. Characteristics of effective programmes

There are some common characteristics that have been evident in successful interventions. These include family and community involvement and early intervention. Cost-effective programmes are either successful because they are able to reach a large population of individuals, or because the impact on each individual is substantial. Involving parents as well as children can have significant impacts because of the role parents play in influencing children’s food and activity choices. Preschool programmes should be family based because the primary social force that influences young children’s health behaviour is the parent. Family-based interventions combining education with behaviour modification are successful.

Evidence on whether dietary or physical activity interventions are more effective is mixed, but many of the successful interventions include both aspects. There is some evidence that boys, in particular, respond better to programmes that have a physical activity focus. An interesting point to note is that activity interventions can have a smaller effect than nutrition interventions, such as reducing fizzy drinks. This is because, for the average 8 year old child, 10 per cent of energy intake is equivalent to 450mL of soft drink (just over one can) whereas 10 per cent of energy expenditure is equivalent to 2.5 hours of extra walking.[11] This does not mean that physical activity is not a worthwhile pursuit but it shows that a certain level of intensity and duration is required to have a measurable impact.

Interventions that limit television viewing or “screen time” are often effective in reducing BMI due to the relationship of these factors with sedentary lifestyle. Many of the successful programmes were focussed on promoting a healthy lifestyle rather than specifically on reducing weight, so included a combination of nutrition education, physical activity and encouragement to change behaviour in the longer term.

Intervention in the early years is important for developing the behaviour and cognitive patterns that will be set for later in life. It has been argued that targeting preschool aged children is central to preventing obesity.[12] This is because development at this life-stage is more malleable than it is later in childhood and adolescence, and risk factors of excess weight can be more easily modified. Medical evidence also suggests that diet in infancy can impact on a child’s longer term health. For example, breastfeeding of infants at an early age tends to be associated with a lower prevalence of obesity later in life. Therefore, cost-effective early years programmes that promote breastfeeding may also have longer term benefits for obesity.

2.6.2. Recruitment to programmes

The Greater London Intelligence Unit Report highlighted that the majority of participants in obesity treatment interventions in the UK were self-referred. They discussed this finding with staff from the Mind Exercise, Nutrition…Do it (MEND)

Programme who noted that over half of participants are self-referred, hearing about the programme from advertisements or word-of-mouth within their community. Participants are also referred to treatment programmes from GPs and school nurses. However, it was found that recruiting children by sending letters to parents as part of the National Child Measurement Programme had only limited success. The main reason identified for a lack of participation in weight management programmes was due to the child not wanting to attend the programme. This was followed by other reasons such as other family commitments, problems with access to programme venues and parental attitudes. An important insight is that many parents believe that their overweight or obese child does not have a problem.

2.6.3. Brief Interventions

This section is based on a review of the literature by West and Saffin for the North West and London Teaching Public Health Networks. Brief interventions are characterised by being provided by suitably trained “professionals” in a variety of settings; being opportunistic in nature; targeting individuals, families or groups; having a limited duration and frequency (e.g. within the space of a single consultation session and no greater than four sessions); consisting of an identification of health issues and assessment of an individual’s motivation and stage of behaviour change; including negotiation, goal, and forward-looking solution setting with provision of advice, counselling, information, or referral as appropriate and follow-up and reinforcement, as appropriate.

Evidence reviews have identified a lack of good quality evidence about the effectiveness of brief interventions for overweight and obese children aged 4 to 11 years in both primary care and other settings. However, because a brief intervention is cheap and opportunistic it has been argued that it is likely to be worthwhile even if gains are modest.

In order to equip professionals with the skills and confidence to talk to families about obesity and to deliver brief interventions for overweight and obese children, training should be provided. Common elements of brief intervention training sessions include combining theory-based didactic teaching with workshops focused on skills-training activities, using role-playing exercises and standardised patients (lay-people trained to consistently replicate a clinical encounter) and delivery by credible experts with feedback. [13]

3 Local Picture

3.1. Measurement of obesity in children

The Health Visiting Service weight and measures children and provides data on the school population. The National Child Measurement Programme records the weight and height of all children attending a state maintained school. The measurement of the school population will include some children that live outside of the borough. Across the country the participation rate is high and the large numbers of children measured provide robust statistics on obesity levels. In Richmond upon Thames participation rates for Reception year have remained constant year on year and Year 6 has seen an improvement from the initial year (2005/06).

Table 2 Participation rate in the school measurement programme

|

School Year |

2005/06 |

2006/07 |

2007/08 |

2008/09 |

2009/10 |

2010/11 |

2011/12 |

2012/13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reception |

92.3% |

91.6% |

94% |

92.5% |

93.5% |

91.3% |

94.5% |

92.9% |

|

Year 6 |

84.5% |

91.4% |

91% |

93.6% |

92.6% |

90% |

91.6% |

92.4% |

The proportion of children that are not measured is not the same across the borough. Schools in Kew, Mortlake, Barnes and East Sheen show the highest proportion of unmeasured Reception children (9.8%). Heathfield, Whitton and West Twickenham schools (5.2%) show the lowest proportion of unmeasured Reception children. Schools in Kew, Mortlake, Barnes and East Sheen show the highest proportion of unmeasured Year 6 children (12.3%). St. Margaret’s, Twickenham and Teddington schools (7.8%) show the lowest proportion of unmeasured Year 6 children. Unmeasured children may introduce a bias, if a larger proportion of them are overweight, but it is unlikely that if included they would sufficiently alter the boroughs statistics to change the conclusions drawn.

It should also be noted that approximately 12% of children in Richmond maintained schools are not residents of the borough and similarly a proportion of children living in Richmond upon Thames will attend schools outside the borough. Again it seems unlikely that this will affect the conclusions drawn from the child measurement data. Furthermore the NCMP data does not capture those children of primary school age that do not attend state maintained schools. Whilst not an exact comparison of like with like we can compare data on the number of children aged five and aged eleven from the 2011 census with the number of children measured in reception and year 6 to gain a good indication of population coverage. In 2011 the census recorded 2446 children aged five and in 2012/13 in reception year 2230 children were measured suggesting that approximately 90% of children of this age were measured. In year 6 more children go to private schools. In 2011 the census recorded 2060 children aged eleven and in 2012/13 a total of 1547 year 6 children were measured, suggesting that approximately 75% of children of this age were measured.

3.2. Findings from Child Measurement data

Based on National Childhood Measurement data for 2012/13, Richmond upon Thames is among the lowest prevalence of overweight and obesity in primary school aged children in England. In reception year 16.3% of children are overweight or obese making Richmond the eight lowest local authority. In Year 6 this has risen to 26.1% making Richmond twenty first lowest prevalence of overweight and obese children. [14]

Table 4: Overweight and Obesity prevalence in Reception and Year 6, 2012/13

|

School Year |

Participation (%) |

Overweight number |

Overweight percentage (%) |

Obese number |

Obese percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reception |

92.9 |

231 |

10.4 |

132 |

5.9 |

|

Year 6 |

92.4 |

190 |

12.3 |

214 |

13.8 |

Source: NCMP 2012/13 data

In Richmond upon Thames and England as a whole there are more males than females who are obese in Reception year and Year 6. The gap seems to widen as children reach Year 6. Some of the difference may be due to some obese females opting out. Over the last 3 years on average in Richmond upon Thames 5.4% of females and 6.8% of males in Reception year were obese. In Year 6 on average 9.5% of females and 14.4% of males were obese.

Figure 2 shows the trend in overweight and obesity among reception and Year 6 children from 2006/07 to 2012/13. Overall, there has been slight variation in the year on year figures. There has been a slight decrease in obesity prevalence in reception since 2010/11, and a slight increase in obesity prevalence in Year 6, for the same period. However minor year on year fluctuations are expected.

Figure 2: Trend in Overweight and Obesity in reception and Year 6 children, in Richmond 2006/07 – 2012/13

Source: NCMP 2005/2006 – 2012/13 data tables

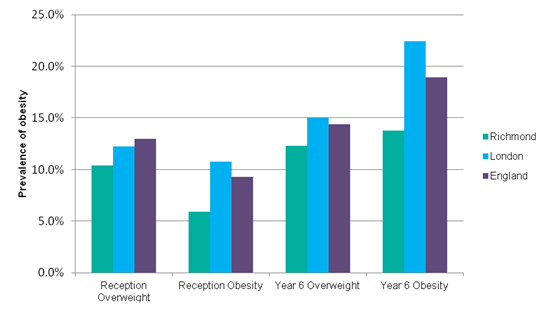

Obesity prevalence for 2012/13 shows that local levels of overweight in Reception year (10.4%) and Year 6 (12.3%) are less than the London prevalence in reception year (12.2%) and Year 6 (15.0%). Local obesity levels (5.9%) in Reception year are less than half of the London prevalence (10.8%) and significantly lower than the England prevalence (9.3%). However, similar to London and England obesity levels double between Reception year and Year 6 (figure 3).

Figure 3: Overweight and Obesity levels in Richmond, London and England, 2012/13

Source: NCMP, 2012/13

Comparing Richmond upon Thames to the South West London sector (figure 4) it has the lowest prevalence of overweight and obese children in Reception and Year 6 children.

Figure 4: Overweight and obesity amongst Reception and Year 6 children in South West London (SWL), 2012/13

Source: NCMP, 2012/13

There is some evidence that in Richmond upon Thames children from ethnic groups other than white are more likely to be obese. Based on pooling data for the years (2007/08-2009/10) there are a larger proportion of obese children in ethnic groups other than white (Table 5).

Table 5: Prevalence of obesity in ethnic group categories in children in Richmond upon Thames between 2007 and 2010

|

Year Group |

white |

black |

Other including Chinese |

Asian |

Mixed |

Not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reception |

5.5% |

21.5% |

8.3% |

8.7% |

5.0% |

6.1% |

|

Year 6 |

10.3% |

25.8% |

17.4% |

18.1% |

14.6% |

15.7% |

Some caution is needed when interpreting this data because the number of children in each ethnic group is small compared to the white group and the confidence intervals around the estimates are wide. Nevertheless the differences are substantial and the difference observed in black children compared to white children is statistically significant.

Comparing the pooled data for Year 6 (2007/08-2009/10) in Richmond upon Thames to prevalence data for the rest of England reveals similar levels of obesity in some but not all ethnic groups (Table 6). In white children and mixed children obesity is much lower but in black, Asian and other ethnic groups including Chinese children it is lower but close to that seen in the rest of England. This data suggests that the reasons for increased obesity amongst certain ethnic groups in England may also apply to the local population.

Table 6: Comparison of obesity in ethnic group categories in children in Richmond upon Thames and England

|

Year Group |

white |

black |

Other including Chinese |

Asian |

Mixed |

Not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

England |

17.4% |

26.0% |

21.8% |

21.8% |

20.9% |

18.4% |

|

Richmond |

10.3% |

25.8% |

17.4% |

18.1% |

14.6% |

15.7% |

Understanding obesity in different populations is a complex area. For example, research in the USA has reported that African America girls may consider themselves to be more attractive and socially acceptable at a higher BMI. Research in East England showed that in Black African girls, obesity was associated with higher self esteem and a low self esteem amongst Bangladeshi girls, while obesity was associated with lower self esteem in White and Bangladeshi girls.

3.3. Summary of Child Measurement data

The National Child Measurement data shows that the overall prevalence of obesity and overweight in primary aged children in Richmond upon Thames is lower than most other areas of England. However like the rest of England obesity prevalence doubles between reception and Year 6. There is some evidence that obesity is higher in some ethnic minority population groups. Whilst overall, the prevalence of excess weight children is lower than other areas it is still too high and a serious public health concern.

4 Local Services

Measures to address obesity include three broad categories:

- “Weight management programmes” targeted at individuals who are already overweight or obese

- Preventative interventions

- Wider prevention activity.

4.1.1. Weight management programmes

Weight management programme’s target individuals and therefore require identification of those who are overweight or obese. In Richmond upon Thames one of the main routes for identifying overweight children is the National Child Measurement Programme. This is done in the school setting by school nurses and parents are informed of the outcome. In addition to the measurement programme children can be identified as being obese via contact with health services. A child may visit the GP for another health reason and can be incidental GP consultation, secondary to primary reason of appointment. Also a child may have a formal assessment following a consultation for a clinical presentation associated with obesity for example reflux symptoms or excess sweating. The small number of children that are obese and have clinical complications are referred to specialist services (see below).

Identification can be undertaken by a wide range of professionals including GPs, Practice nurses, healthcare assistants, health visitors, children’s centre staff, and school nurses. Formal assessment in children requires the use of the 1990 UK growth charts as recommended by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH). To help practitioners there is a tool the BMI calculator on NHS choices (www.nhs.uk/bmi) Using by entering the child’s weight, height, date of birth and date of measurements will calculate the BMI centile. In undertaking this needs assessment, it was found that locally there is inconsistent usage of the tool available at NHS Choices due to staff not aware of this support tool, particularly GPs. Formal assessment should involve classification and if a child is overweight assessing readiness for change.

Readiness for change is crucial, as it is closely linked to successful completion of weight management programmes. Not all children or their families will be ready. Many may not perceive a weight problem, or may not want to participate in a formal programme. It is therefore not necessary to have the capacity in weight management programmes to see all overweight children. Population demand can be sensibly met by supplying sufficient places so that all children above a weight threshold that want to participate can attend. As the unit cost per child of weight management programmes is high, when compared to universal interventions, the level of supply needs to be carefully considered. In Richmond upon Thames, at the time of writing, there were no weight management services running that are available for children or their families. This is problematic for those who identify overweight children and families and is also missing an opportunity to help reduce obesity.

For any targeted obesity interventions an important consideration is the confidence and ability of the health professional to raise the issue of obesity with a child and parent. It is a sensitive subject and there is no information available about the extent to which health professionals in Richmond upon Thames feel able to raise the issue of obesity with families.

4.1.2. Brief Interventions

In Richmond upon Thames there is an inconsistent approach to providing brief interventions. Two school nurses are currently providing brief support to parents who call up the team asking for advice around their child’s status as a result of the NCMP measurement letters that have been sent out to all parents. Locally GPs do not generally provide brief interventions about child obesity. This may be due to time constraints, a lack of confidence in dealing with child obesity issues or a lack of training about providing brief interventions.

4.1.3. Specialist services

GPs in Richmond upon Thames tend only to refer overweight/obese children with co-morbidities or clinical complications to specialist services. The approach used to refer children to specialised support or a dietician is unclear.

Five GPs privately commission Dietetic services for their patients. One GP surgery has open access for all Twickenham registered patients. Clinics run two-three times a month in each practice and waiting times are around two months. No information on uptake for children was available. In addition, Public Health commission a 2 day a month dietician service. This service sees small numbers of children each year in 2011/12, there were 12 children referred into the service and in 2012/13 there were 8 children referred. Referrals are made by GPs, school nurses, dieticians, community paediatrician. Waiting times are around 2-4 weeks.

It is recommended that obese children should have as an option a specialist multi-disciplinary service (dietetics, psychology, physiotherapy/specialist, specialist nurse and pharmacotherapy). There appears to be a lack of a multidisciplinary team or the route into such support is not clear and the option may be available via mental health services. Numbers of children in Richmond upon Thames requiring specialist services for obesity will be small but it is unclear if current service provision and the routes into those services meet population need.

No data was available about the pharmacological treatment of children for obesity and no child under age 18 years has been referred to bariatric surgery since 2010. The remit of this population needs assessment does not cover clinical services.

4.2. Preventative interventions

Preventative interventions are defined here as those that specifically target weight gain in children. There is very limited activity that is focussed solely on preventing child obesity. Healthy Child Programme developmental checks carried out by community nurses working with Children’s Centres are being carried out. Parents are invited to attend a Healthy Child Programme developmental check at age one and two. Checks are carried at Children Centres or community clinics by the health visiting team, who provide parents with healthy eating advice. Uptake of the service is unknown.

4.2.1. Wider prevention activity

Almost all activity currently undertaken to prevent childhood obesity in Richmond upon Thames is a part of wider activity around health, welfare, education and recreation. The advantage of this approach is that it is universal and does not identify or potentially stigmatise obese children. Activity includes specific programmes and actions aimed at promoting healthy eating and physical activity, such as Change 4 Life, Start 4 Life and the Healthy Schools London Award. It also includes the routine work of schools, children’s centres, council and social services in promoting healthy development, and wellbeing. Table 7 highlights some of this provision.

A number of themes emerged from undertaking this mapping of activity the first was a lack of information around participation. This is not surprising as these services and provision are not targeting overweight and obese children. A second issue is the potential for a lack of consistency around the quality of the information provided. We are aware that numerous practitioners and professionals interact with parents of overweight and obese children but do not know how this contact is used and when issues of weight are raised the quality of the information provided to parents. A third point to emerge was the potential to increase impact. There are many opportunities available especially around recreation and physical activity to improve knowledge, uptake and potentially referral to these activities.

Table 7: A selection of wider prevention activity that is related to helping children maintain or reach a healthy weight

|

Age group |

Activity |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

|

0 – 5 |

Start4Life is an online resource available to new mothers and families, providing healthy eating tips and how to stay active. No local lead has been identified to support delivery |

There is no information about local uptake. Opportunity for greater promotion of national programmes i.e. Start4Life, Change4Life, by all professionals involved with healthy eating and active lifestyles. |

|

0 – 5 |

Parents are invited to attend a Healthy Child Programme developmental check at age one and two. Checks are carried at Children Centres or community clinics by the health visiting team, who provide parents with healthy eating.

|

Uptake of the service is unknown. Uncertain if HCP messages are reaching vulnerable children and families that would most benefit. Better data information sharing around HCP uptake with NHS England |

|

0 – 5 |

Children Centres provide a range of physical activity and opportunities to learn about healthy eating and diet to children and families. Uptake unknown

|

Uncertain if reaching those children and families that need it most.

Standardised prevention advice and support should be given out by all health professional to ensure consistency and high standard of information.

|

|

3+ |

There are several sports and fitness centres in the borough, located within local schools and academies, and two council pools. All clubs offer provisions for children aged 3+. Limited free swim passes are available for low income families as well as GP referred children whose condition may be improved from physical activity such as swimming, including those with weight management issues. No uptake data was available for children.

|

Opportunity to promote services so all health professionals linked to prevention opportunities and how to refer in

|

|

4-12 |

Healthy School London Award (HSLA) is voluntary for schools to sign up to. The award encourages schools to increase provisions in physical activity in and out of school, including with community services. It also ensures that schools increase uptake of school meals, healthy packed lunches and access to healthy snacks.

|

15/42 (36%) schools have signed up to the HSLA. Further engagement required to encourage all schools to sign up. Those schools that are signed up need continued encouragement and support in applying for higher awards.

|

|

4-7 |

Universal free school meals for Key stage 1 (reception, Year 1 and Year 2) from Sept 2014 ensures that schools comply with school food standards and offer lunchtime meals, provide meals for pupils with special dietary requirements and set policies regarding packed lunches

|

|

|

4-16 |

National curriculum programme of study for all key stage 3 (up to Year 10) Sept 2014 provides pupils with the understanding of healthy nutrition and skills to prepare basic savoury dishes

|

|

|

3-18 |

There are several sports and fitness centres in the borough, located within local schools and academies, and two council pools. All clubs offer provisions for children aged 3+. Limited free swim passes are available for low income families as well as GP referred children whose condition may be improved from physical activity such as swimming, including those with weight management issues. No uptake data was available for children.

|

Further promotion of services so all health professionals linked to prevention and management of obesity are aware of services and how to refer in

|

|

4-18 |

Richmond Inclusion Sports and Exercise provide a range of disability-specific sport and exercise activity i.e. wheelchair basketball, trampolining etc. During 2013 £8000 were spent of these sports, take up was 1880 attendances (n100) across all activities. |

Opportunity to promote physical activity in those that are disabled |

|

2-18 |

Richmond’s local strategy on Healthy Eating Active Lifestyle 2013/14, led by Public Health highlights some of opportunities and provisions for walking and cycling routes within the borough. Local initiatives including coaching, grass track racing and competitions are also available in secondary schools. The British cycling organisation also provides regular group cycling opportunities. The local cycling steering group also work with residents to improve participation and reduce barriers to cycling provisions.

|

Opportunity to promote physical activity and target front line staff for training or highlighting issues around obesity also opportunity for distribution of material on healthy weight |

4.3. Consideration of local approach

The local approach to reducing child obesity is almost entirely through wider prevention activity undertaken by a range of people in different settings. This includes children’s centres, schools, recreation services, council services and health professionals. Each is acting largely independently of each other. It is impossible to know the impact of this effort as data is not collected, but the overall level of child obesity in Richmond upon Thames is lower than in many other boroughs. The advantage of this non-systematic approach to child obesity is that it does not use resources to coordinate effort. However there are disadvantages, it signals that child obesity is not seen as an important public health issue and the lack of coordination means it is unable to maximise opportunities to have an impact.

A probable consequence of not currently having a coordinated approach is the gap in service provision for children that are identified as overweight and obese. At the time of writing there were no community weight management interventions in Richmond upon Thames. Community weight management interventions are costly and the supply for the population needs to be carefully considered, but having no provision creates the problem of not having a range of options to offer families of children that are identified as obese. This is especially problematic because the results of the child measurement programme are categorised and parents are informed if their child is overweight or obese.

Parents that seek support because their child’s measurement is categorised as overweight or obese usually talk to a school nurse and are informed about national websites and are provided with limited support depending upon the skills of the nurse. The situation is likely to be similar for children identified as obese by other professionals as there is no clear pathway to follow or training structures in place. Ideally families would be provided with consistent information, signposting to services and the opportunity to access a suite of interventions or activities that encouraged healthy weight but this is only possible if the whole approach becomes more systematic.

Making the approach to child obesity more systematic requires resource and there is very limited public health (dedicated time) or financial resource available. There are also competing opportunities for this resource so it must be used wisely. Adding value to the existing universal approaches is likely to be good value for money and a balance needs to be made between commissioning new interventions and better support for existing activity. Support for existing activity should aim to improve knowledge and awareness among providers about how they can use their interactions with children to help them to maintain or reach a healthy weight and also to improve the quality of information provided to families. The following improvements could be made:

- ensuring high quality standard materials and information are available and offered to families around child nutrition and healthy weight

- ensuring that frontline staff such as school nurses and children’s centre workers receive training about child obesity and are able to communicate effectively with families

- Encouraging greater involvement of families in physical activity and an ethos of mass participation in sports and recreation

Linking new interventions to existing infrastructure is likely to improve their cost effectiveness. For example, the offer of a brief intervention can be linked with the school measurement programme and activity of children’s centres. It is however also important to promote self-referrals to interventions or activities as evidence indicates high success rates in those that are motivated to change. A key period for targeting interventions is between reception year and year six, as obesity doubles during this period. Supporting activity in primary schools is crucial.

The majority of the local population are affluent and well educated, and careful consideration is needed around the type and delivery of interventions. For example, a brief intervention to motivate a family may best be provided by a qualified professional such as a nutritionist. In considering new interventions their cost and population impact needs to be evaluated to ensure value for money. An overall aim should be identifying interventions that are cost effective and acceptable to the local population.

In general a more systematic and strategic approach is needed to support existing universal offers and promote an environment across the borough which will have a positive impact on reducing obesity without stigmatising children. Some new targeted interventions are needed as is greater clarity about what is available, the best information to provide families, and what frontline staff should do to help children that are overweight or obese reach a healthy weight.

5 Conclusion

Child obesity in Richmond upon Thames is not as bad as in other areas of England but it is a still too high and a preventable public health issue. Reducing child obesity is difficult and there are limitations around what can be achieved at the borough level. However there is good evidence to show that early intervention is important and approaches that include schools, family and community involvement yield positive results.

In Richmond upon Thames local activity to reduce child obesity is mainly wider prevention activity, such as, promoting the Healthy School London Award and the routine activity of children’s centres, schools, and clubs in encouraging children to undertake physical activity and eat a healthy diet. These non-stigmatising types of activity are in keeping with the evidence and further universal effort is encouraged especially for primary school age children. However at the time of writing current activity is not sufficiently joined up and there are gaps in provision, notably the lack of a weight management programme for children identified as being obese. A more coordinated approach would help, but this requires a resource. The extent of the coordination and commitment of the public health team needed to gain cost effective benefits requires careful consideration. Given resource constraints actions that utilise available infrastructure and resources should be a priority, such as providing standardised information to families and training for frontline staff so they can provide high quality advice. Key resources are the Children’s centres and primary schools with school nurses being important. The Child Measurement Programme offers a way to identify obese children but it is important that readiness for change is considered and any interventions available for obese children are attractive to the local population.

6 Recommendations

Child obesity is a complex issue requiring action at many levels from the European Union, national governments, food industry, large organisations, and locally from local councils, schools, communities and parents. The following recommendations are based on the findings of this local needs assessment and are largely for local authority and community led action to help create in Richmond upon Thames an environment that supports and facilitates healthy choices by children and families. The overall aim of the recommendations is to better use available infrastructure and ensure some provision of options for families of children identified as overweight and obese.

It is recommended that:

- Public Health should engage and work with council colleagues and partners with the aim of ensuring visions, principles, strategies and policy documents linked to physical activity and healthy eating support and facilitate healthy choices by children and families.

- The school setting, particular primary schools should be used as a facilitator of healthy choices by children. Whole school approaches to health eating should be supported that do not target and risk stigmatising pupils. Work to ensure schools are signed up and committed to the Healthy School London Award is supported.

- Public Health should provide leadership and actions to ensure that parents receive consistent high quality messages and information about child obesity. A short “top tips” style guide about positive actions a family with young children can take to reach and maintain a healthy weight should be developed using high quality sources of information and this should be made available to key frontline staff, such as school nurses and put on the website. The guide should include references to a small number of trusted websites such as NHS Choices. These should be the websites that are recommended to parents.

- Consideration should be given by public health and the council to how best to improve the knowledge and skills of key frontline staff around child obesity. This might include the provision of training for some groups such as children’s and leisure centre workers.

- School nurses involved with the School Measurement Programme should have the skills and confidence to communicate with parents about a child being overweight or obese. Public Health should use commissioning opportunities and work with school nurses to ensure they have the necessary training.

- Public Health should consider the most cost effective way to provide brief interventions to children and their families. This should include appraising options such as having a nutritionist delivering advice and motivational interviews. Before commissioning a new service options should be piloted and evaluated for their cost effectiveness.

- Public Health should commission or develop a service or intervention that can be offered to the families of all children identified as being obese or overweight by the school measurement programme. Options to consider should include a family orientated weight management programme and be in keeping with recommendations from NICE public health guidance 47 – Managing overweight and obesity among children and young people: lifestyle weight management services. Any new service should be available for referrals by GPs and for self-referral.

- Relevant guidance such as Public Health NICE guidance Ph27 – Promoting physical activity for children and young people and partnership building is used to exploit local assets such as parks, clubs and recreation facilities to increase opportunities for families and children to be physically active

7 References

[1] https://catalogue.ic.nhs.uk/publications/public-health/obesity/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2011/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2011-rep.pdf

[2] NICE 2007 https://publications.nice.org.uk/obesity-working-with-local-communities-ph42/glossary#overweight-and-obesity-adults

[3] Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, 2011. The influence of maternal, foetal, and child nutrition on the development of chronic disease in later life. https://www.sacn.gov.uk/reports_position_statements/reports/the_influence_of_maternal_fetal_and_child_nutrition_on_the_development_of_chronic_disease_in_later_life.html

[4] McCormick, B. Stone, I. and Corporate Analytical Team. 2007. “Economic costs of obesity and the case for government intervention”. Obesity reviews 8 (Suppl.1), 161-164

[5] Childhood Obesity in London. Greater London Authority April 2011

[6] Kipping, R. Jago, R. and Lawlor, D. 2008. “Obesity in children: Part 1: Epidemiology, measurement,risk factors and screening”. BMJ; 337:a1824

[7] Strauss R., Childhood obesity and self esteem, Pediatrics 2000; 105; e15

[8] https://www.richmond.gov.uk/richmond_young_peoples_survey

[9] Childhood Obesity in London. Greater London Authority April 2011

[10] Noo https://www.noo.org.uk/gsf.php5?f=14604

[11] Swinburn, B. Jolley, D. Kremer, P. Salbe, A. and Ravussin, E. “Estimating the effects of energy imbalance on changes in body weight in children”. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 83:11-17.

[12] Skuoteris, H. McCabe, M. Swinburn, B. Newgreen, V. Sacher, P. and Chadwick, P. 2010. “Parental influence and obesity prevention in pre-schoolers: a systematic review of interventions”. Obesity reviews.

[13] Douglas West and Kate Saffin. Literature review: Brief interventions and childhood obesity for North West and London Teaching Public Health Networks 2008.

[14] PHE https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/national-child-measurement-programme#gid/8000011/pat/6/ati/102/page/1/par/E12000007/are/E09000027

Document Information

Published: September 2014

For Review: September 2017

Public Health Topic Lead: Clair Harris, Public Health Principal