1 Executive Summary

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a type of sexual abuse in which children are sexually exploited for money, power or status.

An overview of best practice is provided in this report, helping to guide local services on how they can most effectively work together to address this issue. All local areas are expected to review their strategic and operational plans against the framework developed by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner; the key principles and foundations of good practice are outlined in this report. Key local partners in Richmond borough should ensure that the following functions, processes and structures are in place:

- Accountability for all safeguarding and strategic coordination

- Multi-agency strategic planning on CSE

- Partnership and information sharing for identification and assessment

- Coordination of multi-agency strategic groups

- Intervention and service delivery:

- Prevention

- Pre-emptive policing to forestall exploitation

- Targeted early intervention

- Enduring support for victims and families

- Identification/apprehension of perpetrators and monitoring of non-convicted suspects

- Rehabilitation of offenders

This report also aims to present a population level perspective of the known risk factors among children and young people in Richmond which relate to CSE. The complex and hidden nature of CSE means that it is very difficult to provide an accurate number of either current or former victims of CSE. This report focuses on the local prevalence of risk factors associated with CSE, to allow for services and commissioners to understand who may be at risk locally from CSE and ensure that support is focused on these vulnerable children within the highest risk factor groups.

Key points on prevalence of risk and protective factors at the population level:

Protective Factors

- Richmond has a relatively low rate of children in need

- The teenage conception rate is relatively low in Richmond

- Richmond has the lowest domestic abuse incident rate in London

Risk Factors

- The rate of children who are the subject of a child protection plan has doubled in the past five years, with 115 children recorded as at March 2015

- Around 80% of looked after children are placed in care outside the borough

- Out of 150 children looked after during 2014-15, 25 children had a ‘missing incident’ during the year. The average number of missing incidents per looked after child (6.1 incidents) is relatively high.

- In 2014-15 approximately 220 children were in households that were living in temporary accommodation

- It is estimated that there are almost 2,000 children aged 5-16 with a mental health disorder. 5% of 11-16 year-olds are estimated to experience mental health problems.

- Rate of hospital admissions following self-harm is relatively high in Richmond

- 15-year-olds in Richmond engage in significantly more risky behaviours compared to their peers. Almost one-quarter report being drunk in the last four weeks and one-fifth report having ever tried cannabis – the highest percentages in London.

- Richmond is not identified as an area with a gang problem, but this is an issue in neighbouring boroughs and there is significant migration between boroughs in school and looked-after children populations.

- There are 20 unaccompanied asylum seeking children in Richmond

The main recommendations are for local services to use the data on prevalence of risk factors to help support their work, and for the LSCB CSE subgroup to carry out an assessment of local services and approach against the best practice guidance.

2 Introduction

This report aims to present a population level perspective of the known risk factors among children and young people in Richmond which relate to child sexual exploitation (CSE). It gives some quantitative estimate of risks based on profiling factors known to be associated with CSE. It therefore indicates the potential scale of the problem, however CSE is extremely complex and often hidden so the true extent of the issues cannot be clearly profiled. Information relating to a number of factors is not readily available and therefore a comprehensive picture is not possible. Nevertheless this profile of known risk factors for CSE gives an initial assessment to help guide the Richmond prevention strategy and action planning to protect all children and reduce CSE. The devastating effect of CSE on both the individual child and their family means that CSE must be a high priority for all partners working with children.

3 Background

3.1. Introduction

In March 2015, the Prime Minister unveiled new measures to tackle child sexual exploitation, arising from investigations into historic cases of child sexual exploitation. These reports document numerous, significant issues across services to share information and to protect children. An overview of best practice is provided in this report, helping to guide local services on how they can most effectively work together to address this issue.

The Local Safeguarding Children Board has provided a platform for stakeholders to discuss and implement guidance for practitioners on identification of children who are potentially at risk of sexual exploitation.

Population level data on risk factors should inform an estimation of the potential scale of this issue and the level of risk of CSE in the borough of Richmond in order to efficiently plan services and to protect vulnerable children.

3.2. Methodology

The Local Safeguarding Children Board provides guidance to aide practitioners in recognising warning signs for children and young people who may be at risk of sexual exploitation. The “SAFEGUARD” list of vulnerabilities are consistent with risk factors identified by other literature on safeguarding children from sexual exploitation. This guidance was used as the basis for identifying risk factors in this Health Needs Assessment – see appendix 1 for the full list.

Benchmarking: Kingston has been provided as a benchmark, as it is the most similar borough to,[1] and shares children’s services with Richmond. Where possible, rates per 10,000 children are provided from 2010/11, to enable an analysis of trends.

This document aims to collate population level information on the risk factors of CSE and assess the ease of accessibility of these data. The risk factors are broken down into groups: social services, health services, education services and police. Finally the adequacy of available data and its accessibility will be discussed.

This report has taken a population level perspective to quantify the risk factors of CSE in Richmond to give an idea of the potential scale of the problem. We did not attempt to associate any weight to the level of risk associated with each risk factor, approximate the degree to which factors overlap or give an overall approximation of the absolute number of children at risk.

Data was not available on a number of risk factors or was only known at an individual rather than population level for others. Collaboration is necessary in sharing relevant information across organisations. There is no tool available to estimate the prevalence of CSE in the population. A Bernardo’s Sexual Exploitation Risk Assessment Framework (SERAF) has the potential to be a prevalence tool if used nationally to estimate and monitor the extent of the issue locally.

3.3. What is child sexual exploitation?

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a type of sexual abuse in which children are sexually exploited for money, power or status[2]. A common feature of CSE is that the child or young person does not recognise the coercive nature of the relationship and does not see themselves as a victim of exploitation.

The UK National Working Group for Sexually Exploited Children and Young People (NWG) created an official definition of CSE that is used in national statutory guidance[3]:

“Sexual exploitation of children and young people under 18 involves exploitative situations, contexts and relationships where young people (or a third person or persons) receive ‘something’ (e.g. food, accommodation, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, affection, gifts, money) as a result of them performing, and/or another or others performing on them, sexual activities.

“Child sexual exploitation can occur through the use of technology without the child’s immediate recognition; for example being persuaded to post sexual images on the Internet/mobile phones without immediate payment or gain.

“In all cases, those exploiting the child/young person have power over them by virtue of their age, gender, intellect, physical strength and/or economic or other resources. Violence, coercion and intimidation are common, involvement in exploitative relationships being characterised in the main by the child or young person’s limited availability of choice resulting from their social/economic and/or emotional vulnerability.”

However, one of the recommendations of the Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups[4] (henceforth the CSEGG Inquiry) was that the definition given above should be reviewed.

It is important to note that, even if a young person is 16 or 17 and has reached the legal age of consent, they are defined as children under the Children’s Act 1989 and 2004 and are still at risk of sexual exploitation. The London CSE Operating Protocol states that “Their right to support and protection from harm should not, therefore, be ignored or downgraded by services because they are over the age of 16, or are no longer in mainstream education.”[5]

3.4. Types of CSE

A 2011 Barnardo’s report identified five types of CSE:

- inappropriate relationships – usually involving one offender who has inappropriate power or physical, emotional or financial control over a young person. The young person may believe they are in a loving relationship;

- boyfriend model – the offender befriends and grooms a young person into a relationship and then coerces or forces them to have sex with friends or associates;

- peer-on-peer exploitation – where young people are forced or coerced into sexual activity by peers or associates;

- gang-associated CSE – a young person or child is sexually exploited by a gang, for example using sex as a weapon between rival gangs, as a form of punishment to fellow gang members and/or as a means of gaining status within the hierarchy of the gang;

- organised/networked sexual exploitation or trafficking – young people are passed through networks, sometimes between towns and cities, where they may be forced/coerced into sexual activity with multiple men, often at ‘parties’. Some of this is serious organised crime involving the buying and selling of young people by offenders.

This list highlights the fact that, rather than a child or young person being exploited by someone previously unknown to them, in fact it is more likely that the exploitation is carried out by someone who they consider close to them – for example a ‘boyfriend’, peer, family member or community member.

The CSEGG Inquiry went further and identified 13 patterns of CSE across gangs and groups, many of which have previously been ignored or mis-categorised:

- Group-associated sexual exploitation:

- Exploitation in exchange for accommodation, money or gifts

- Targeting of residential children’s home

- Party model of commercial exploitation

- Linked to intra-familial child sexual abuse

- Linked to transport hubs

- Identified in gang and other group contexts:

- Peer-on-peer exploitation

- Linked to sexual bullying in schools

- Commercial Exploitation linked to other offending such as drugs sales

- Internal trafficking

- Gang-associated sexual exploitation:

- As a weapon in gang conflict

- Used to ‘set up’ rivals

- As a form of punishment to members

- As a form of gang initiation

It is important to note the use of technology in CSE, particularly on-line grooming prior to meeting face-to-face.

3.5. What is the national picture?

Victims

Due to the hidden nature of CSE, establishing an accurate number of current or former victims of CSE nationally is difficult. The CSEGG Inquiry estimated that a total of 2,409 children were known to be victims of CSE by gangs and groups during the 14-month period from August 2010 to October 2011, and 16,500 children and young people were identified as being at risk of CSE in one year (April 2010-March 2011). However data was not received from all local authorities and agencies, and there will be underreporting in the areas that did respond, so these figures are certainly “an undercounting of the true scale of this form of abuse”. CSE is thought to be far more widespread than previously recognised and victims come from all social, economic and ethnic backgrounds and communities.

A CEOP thematic analysis[6] indicated that the most common age that children came to the attention of agencies was 14 and 15. The CSEGG Inquiry ascertained that children are being victimised from the age of 10 upwards and Barnardos have reported that “…victims are becoming younger and the exploitation more sophisticated, involving organised networks that move children from place to place to be abused.”[7] Victims are predominantly female; however, the number of male victims may be underreported due to the difficulties in recognising sexual exploitation amongst boys and young men.

The majority of victims identified are from white ethnic groups, but children from minority ethnic backgrounds may face barriers to reporting and accessing services, so cases of CSE in these communities may be underreported.

Perpetrators

The CEOP thematic analysis found that the vast majority of perpetrators were men, and more than half were under 25 years old, commenting that “the relative youth of the offender population is a striking feature of the data that is distinct from a common profile of the older male abuser.”

Perpetrators come from a range of ethnic backgrounds and recent high profile inquiries in Rotherham, Oxford and Rochdale have involved men of predominantly British-Pakistani backgrounds. The CEOP thematic analysis identified roughly a third of perpetrators as white and a third as Asian, although they reported that ethnicity data was generally of poor quality.

3.6. What are the risk factors?

The CSEGG Inquiry concluded that children are more vulnerable to CSE if they have experienced one or more of the following:

- Living in a chaotic or dysfunctional household (including parental substance use, domestic violence, parental mental health issues, parental criminality);

- History of abuse (including familial child sexual abuse, risk of forced marriage, risk of ‘honour’-based violence, physical and emotional abuse and neglect);

- Recent bereavement or loss;

- Gang association either through relatives, peers or intimate relationships (in cases of gang associated CSE only);

- Attending school with young people who are sexually exploited;

- Learning disabilities;

- Unsure or unable to disclose their sexual orientation to their families;

- Friends with young people who are sexually exploited;

- Homeless;

- Lacking friends from the same age group;

- Living in a gang neighbourhood;

- Living in residential care;

- Living in hostel, bed and breakfast accommodation or a foyer;

- Low self-esteem or self-confidence;

- Young carer; and

- Having been trafficked, either into or within the UK.

In addition, the Inquiry identified the following signs and behaviour that are generally seen in children who are CSE victims:

- Missing from home or care;

- Physical injuries;

- Drug or alcohol misuse;

- Involvement in offending;

- Repeat sexually-transmitted infections, pregnancy and terminations;

- Absent from school;

- Change in physical appearance;

- Evidence of sexual bullying and/or vulnerability through the internet and/or social networking sites;

- Estranged from their family;

- Receipt of gifts from unknown sources;

- Recruiting others into exploitative situations;

- Poor mental health; and

- Self-harm.

The above are all risk factors that increase the likeliness of a child being sexually exploited. Protective factors are elements that reduce the likeliness of a child being sexually exploited for instance family support.

The London CSE Operating Protocol[8] has distilled these risk factors and behaviours into the SAFEGUARD mnemonic to assist those working with children and young people in remembering and assessing the signs and behaviours associated with CSE (see Figure 1). However, the SAFEGUARD mnemonic does not explicitly mention minority groups such as those with learning disabilities, those from BME communities and LGBT youth that have been shown to be more vulnerable to CSE. An added issue in the case of some of these groups is that they may not access services as readily as other groups, so there is less opportunity for health and social care professionals and others to identify whether they may be at risk of CSE.

Figure 1. The SAFEGUARD mnemonic

3.7. What is the impact on victims and their families?

Being a victim of CSE can have a devastating long term impact on a child or young person’s life, and on their family. Barnardos have outlined the numerous serious health effects that CSE can have on a child or young person[9] which include both psychological issues such as anxiety, depression, self-harm, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and risk of suicide, and physical issues such as injuries, drug addiction, pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. There is also a broad social impact including isolation from friends and family, withdrawal from education, hobbies and interests, difficulty developing relationships and possibly financial difficulties, criminality and housing problems. It is therefore vitally important that support services recognise the wide range of potential impacts on a child or young person, and continue to provide support and services to them for a prolonged period.

CSE can also have a serious impact on the child or young person’s family. Parents against child sexual exploitation (Pace) states that parents report feelings of anger, guilt, shame and profound isolation[10]. Practically, parents may find it very difficult to deal with their child, who may be acting violently or out of control, truanting from school and in trouble with police. The perpetrators involved may attempt to intimidate the child and their family, which may involve direct action or indirect threats in person, to relatives or friends, or via social media[11]. In addition, exploitation of one child in the family places other children in the family at risk of CSE. Parents’ work and relationships may suffer due to the stress and exhaustion.

3.8. Key principles of a good CSE service

“I recognise that child sexual exploitation is hard to tackle. It is complex, sometimes

thankless and very hard to get it right. But it is vital that public services face up to difficult tasks.” Louise Casey, Report of Inspection of Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council, January 2015

Despite authorities and agencies being aware of CSE for many years, it is only recently that the focus of services and the response of agencies and authorities has dramatically altered. Previously it was common that sexually exploited children were referred to as ‘promiscuous’ or ‘prostitutes’, and even treated as offenders. Many were not believed or were dismissed by authorities as ‘putting themselves at risk’[12]. Now they are rightly viewed as victims of sexual, physical and emotional abuse, and in some cases neglect, and are recognised as being in need of immediate protection[13]. Children do not make informed choices to enter or remain in sexual exploitation, but do so from coercion, enticement, manipulation or desperation, and consequently they may have multiple vulnerabilities which require a coordinated multi-agency response7.

In order to facilitate the sea change in the response to CSE, the government published statutory guidance on safeguarding children and young people from CSE in 2009[14], which outlined key principles which should inform effective practice for those working with children and young people who are at risk of, or are suffering, sexual exploitation:

- A child centred approach

- Taking a proactive approach Parenting, family life and services

- The rights of children and young people

- Responsibility for criminal acts

- An integrated approach

- A shared responsibility

These key principles have been echoed in the many inquiries and serious case reports that have been published since in areas such as Rotherham[15], Rochdale[16], Oxford[17] and Manchester[18]. The same issues of silo working and lack of communication across agencies, ignoring and/or disbelieving the child and lack of leadership have been repeatedly raised as reasons why CSE was not effectively addressed at an earlier stage in these and other areas.

However, the CSEGG Inquiry, in its November 2013 final report, identified continued failings in agency and authority responses to CSE and proposed seven essential principles for safeguarding children from CSE:

- The child’s best interests must be the top priority – examples of good practice always focus on the child, their needs and their protection;

- Participation of children and young people – the CSEGG Inquiry identified a significant difference between children and young people’s views of their needs and what would help them, and professionals’ understanding of what would help;

- Enduring relationships and support – gaining a child’s confidence and trust is important to enable children and young people to recognise abuse and feel supported to be able to tell someone about it. The CSEGG Inquiry was told that a consistent person who sticks with the victim throughout the whole period of their protection and ongoing care is crucial to their recovery;

- Comprehensive problem-profiling – to avoid some patterns of sexual exploitation being ignored and to obtain a detailed picture of CSE in the local area to inform action and prevention across all agencies;

- Effective information-sharing within and between agencies – identification of the risk factors and behaviours that are linked to CSE can occur in a wide variety of services and settings, and the victim may engage with a number of services over time, for example attend school, visit a GUM clinic and go to a youth centre. When information on CSE risk is shared within and between these services it allows a comprehensive picture to be built around the child which may trigger an intervention that would otherwise have been missed. The CSEGG Inquiry recommends a cross sector information sharing protocol signed by all relevant partners;

- Supervision, support and training for staff – staff need good leadership, direction, resources and support to be able to carry out work on CSE effectively;

- Evaluation and review – to ensure services and interventions are achieving their intended outcomes and meeting the child or young person’s needs. Children and young people must be directly involved in this.

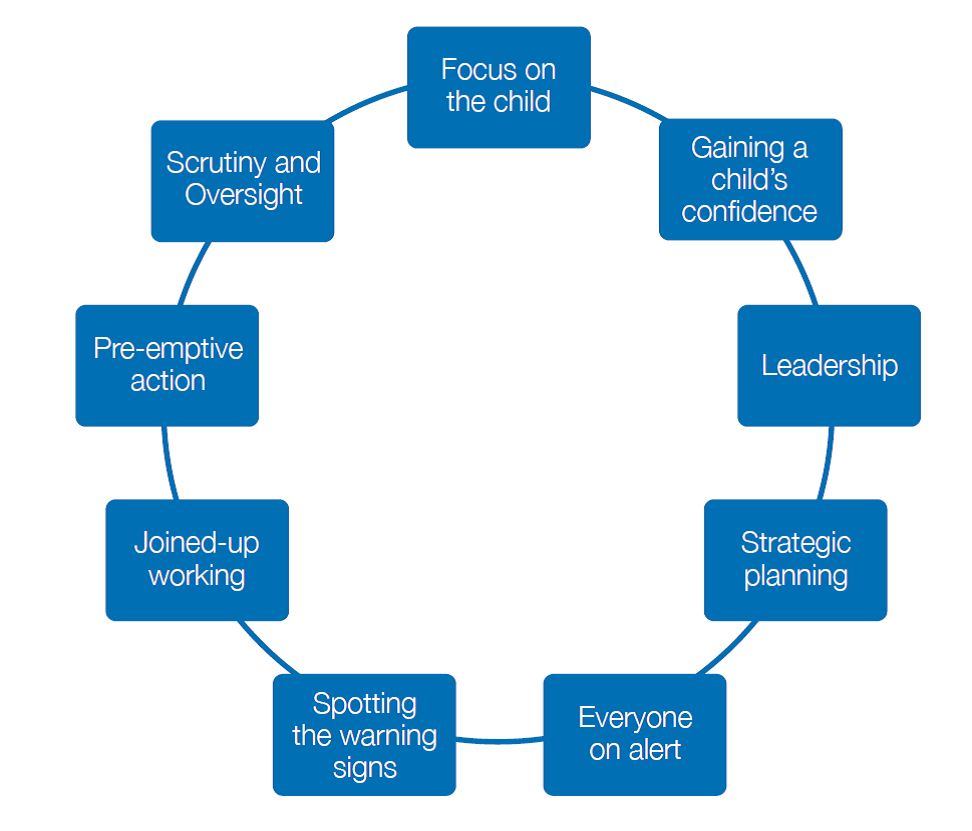

They have also developed nine foundations of good CSE practice (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nine foundations of good CSE practice

These principles and foundations underpin the ’See Me Hear Me’ strategic and operational framework that the Office of the Children’s Commissioner has developed for CSE services, based on the evidence heard by the CSEGG Inquiry. This framework identifies the essential things that need to be in place to ensure effective local responses to CSE, and contains three set of essential questions from the child’s perspective, the professional’s perspective and for the agencies involved in keeping children safe[19], see Appendix 2. All local areas are expected to review their strategic and operational plans against the framework, ensuring that the following functions, processes and structures are in place:

- Accountability for all safeguarding and strategic coordination

- Multi-agency strategic planning on CSE

- Partnership and information sharing for identification and assessment

- Coordination of multi-agency strategic groups

- Intervention and service delivery:

- Prevention

- Pre-emptive policing to forestall exploitation

- Targeted early intervention

- Enduring support for victims and families

- Identification/apprehension of perpetrators and monitoring of non-convicted suspects

- Rehabilitation of offenders

The See Me Hear Me framework approach to CSE services is currently being piloted by three councils in England, with a formal evaluation by the University of Sussex.

As well as ensuring that services meet the requirements of the See Me Hear Me framework, the NWG Network has produced a benchmark questionnaire for LSCBs (see Appendix 3) to assess their response to CSE from the strategic direction set, through prevention and awareness raising to identification and support for victims, and disruption and prosecution of perpetrators.

In addition, the OFSTED 2014 report “It couldn’t happen here, could it?”[20] details a number of recommendations for LSCBs, local authorities and their partners, which were formulated as a result of a thematic inspection of eight local authorities. The recommendations champion a cohesive approach, information sharing, strong leadership, managerial oversight and the importance of specialised CSE training for everyone involved in the care and protection of vulnerable children.

The Local Government Association have produced a resource pack for councils which includes a useful section on the myths and realities of CSE, following “sector wide concerns that stereotypes and myths about this crime could lead to a narrow focus on one particular form of CSE”[21], thus leaving children and young people vulnerable and unsupported.

In London, the London CSE Operating Protocol (2nd edition), published in March 2015, outlines in detail the expected arrangements at a local level for CSE services from all agencies. It emphasises that a multi-agency network or planning meeting/discussion should take place for all children considered at risk of sexual exploitation, and “Child Protection Procedures should always be followed as appropriate in relation to the risk assessment”[22].

The Health Working Group Report on Child Sexual Exploitation[23] gives a helpful explanation as to why a good response to child sexual exploitation requires a multi-agency approach: “each agency has specific responsibilities and expertise:

- the police interrupts and investigates the perpetrator/s;

- children’s social care intervenes to promote positive relationships and living arrangements for the child;

- education connects or reconnects the child with learning and achievement; and

- healthcare staff can identify the victims as well as the physical, psychological and emotional health consequences of the abuse and help the child with recovery.

Children need individual agency contributions to be competent and confident at every point along the child sexual exploitation care pathway – from prevention, through protection to recovery and from information sharing, through joint working to review.”

3.9. Specific guidance for education services

Education services are central to both the prevention of CSE and in recognising those at risk. In terms of prevention, the CSEGG Inquiry recommended that relationships and sex education, including CSE awareness, should be provided by trained practitioners in every educational setting for all children. Richmond Public Health carried out a rapid review of resources to support schools in raising awareness of CSE in January 2015[24].

3.10. Specific guidance for health services

Linked to education, school nurses have been identified as a key group in early recognition of risk factors and of potential victims, and PHE have produced detailed guidance for this sector[25]. The guidance sets out the following principles for school nursing teams:

- Supporting positive staff experience – teams are motivated and confident in helping children at risk of sexual exploitation;

- Building and strengthening leadership – teams have a role in leading, coordinating and contributing to supportive partnerships with other agencies;

- Maximising health and wellbeing – teams have a role in raising awareness and supporting children at risk of sexual exploitation;

- Defining high quality care and measuring impact – teams must offer a quality service which improves the health outcomes for children at risk of sexual exploitation;

- Working with young people to provide a positive experience – ensure their services are young people friendly

- Ensuring the right staff with right skills, in the right place – teams must be equipped to support the needs of children at risk of sexual exploitation

All health services have a pivotal role to play in recognition of risk factors for CSE in children and young people who attend their service, and in providing ongoing support services to victims. In particular, a health service may be the only publicly provided service that a victim of CSE attends, particularly if they are over 16 and no longer attend school, so the need for vigilance and recognition is high. Health services that a victim, or someone at risk, may attend range from A&E and GUM services to substance misuse programmes, CAMHS and GP practices.

Recognising the responsibility that health professionals have to tackle CSE, the Department of Health formed an independent Working Group on CSE aimed at improving the outcomes for children by promoting effective engagement of health services and staff[26] which issued 13 high level recommendations to improve the health service’s response to CSE. Subsequent work by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges produced guidance on improving recognition and response in health settings, aimed at frontline clinicians[27]. In relation to public health, this guidance recommends that the public health community work closely with local LSCBs to improve awareness of CSE and of the help available in local communities and schools, and to build resilience and awareness in children and young people to prevent them being sexually exploited.

3.11. Multi-agency Working

There needs to be multi-agency working to identify and help children at risk. A lot of work has been done to help police and people who work with children on a regular basis to identify those children at risk of being exploited. Given the gravity of offences and the vulnerability of children, any single case is unacceptable. With growing awareness of the issue, there seems to be a growing recognition that the cases found to date only scratch the service of the problem. At a recent Kingston and Richmond LSCB mini-conference on Missing Children & Child Sexual Exploitation, the superintendent from the Richmond metropolitan police encouraged the assembled practitioners to “think the unthinkable” in terms of risk.

4 Local Picture

The complex and hidden nature of child sexual exploitation means that definitive data on the number of CSE is significantly underreported and it is very difficult to provide an accurate number of either current or former victims of CSE. This section focuses on the local prevalence of risk factors associated with CSE, to allow for services and commissioners to understand who may be at risk locally from CSE and ensure that support is focused on these vulnerable children within the risk factor groups. Children who have one or more of these risk factors are not necessarily victims of CSE, equally there may be victims of CSE who did not have any of these risk factors.

4.1. Child population

There will be an increase in the absolute number of children in the population to 2020 of roughly 7%, which is higher than the England average but similar to the London Average.

Table 1 Population aged under 19, projections 2015 to 2020

|

|

2016 |

2020 |

% increase |

|

Richmond upon Thames |

47,500 |

50,800 |

7% |

Source: ONS Subnational population projections for England: 2014-based[28]

4.2. Social Services

Children in need or subject to a child protection plan

Figures for children in need and on a child protection plan will be presented as of 31st March in each year. This is to avoid double counting of children as a child can start or end an episode of need more than once during the year.[29]

A child in need is legally defined as any child that is unlikely or does not have the opportunity to achieve or maintain a reasonable standard of health or development without provision of services from the local authority.[30]

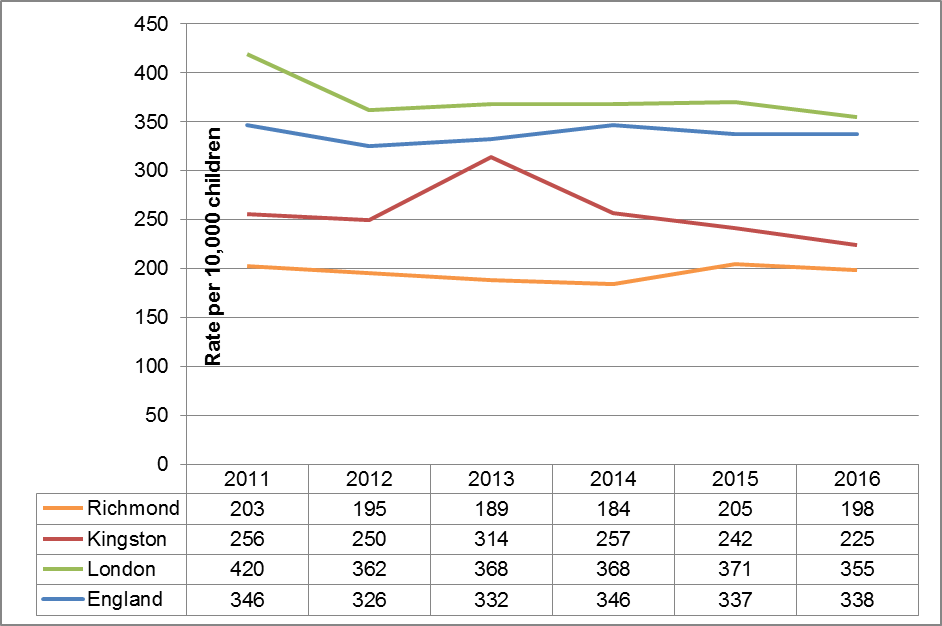

All open cases that have been referred to children’s social care services in the local authorities, as of 31st March each year are listed in Table 2 below. Richmond has the lowest rate of children in need across the regions benchmarked, but was at its highest rate in 5 years in 2014/15. 843 children had an open referral to children’s social services on 31st March 2016.

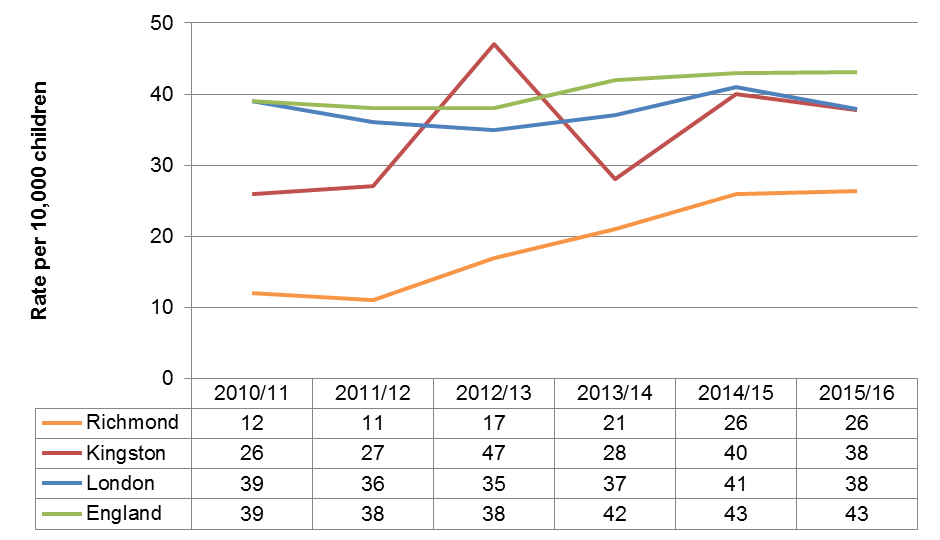

Figure 3 Rate of children in need at 31 March per 10,000 children

Source: Department of Education 2016 – Statistics: children in need and child protection [31]

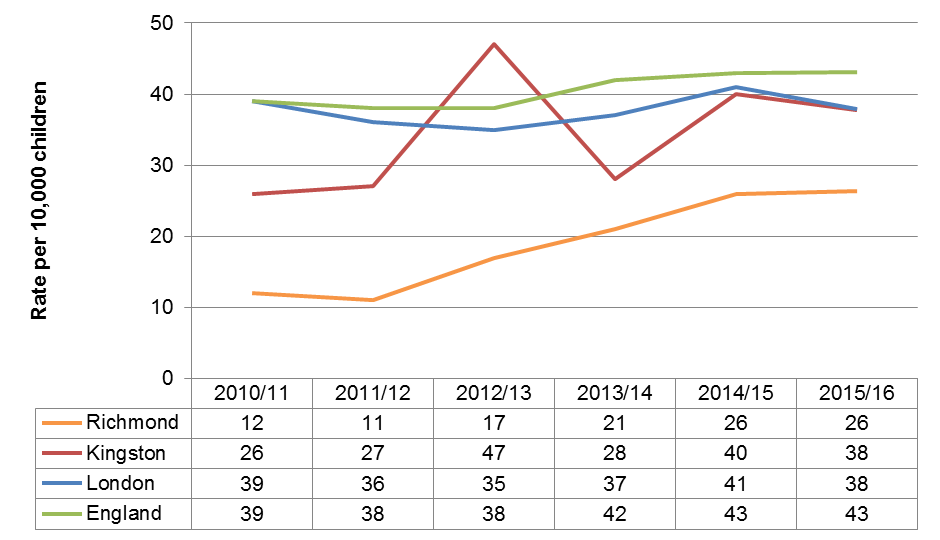

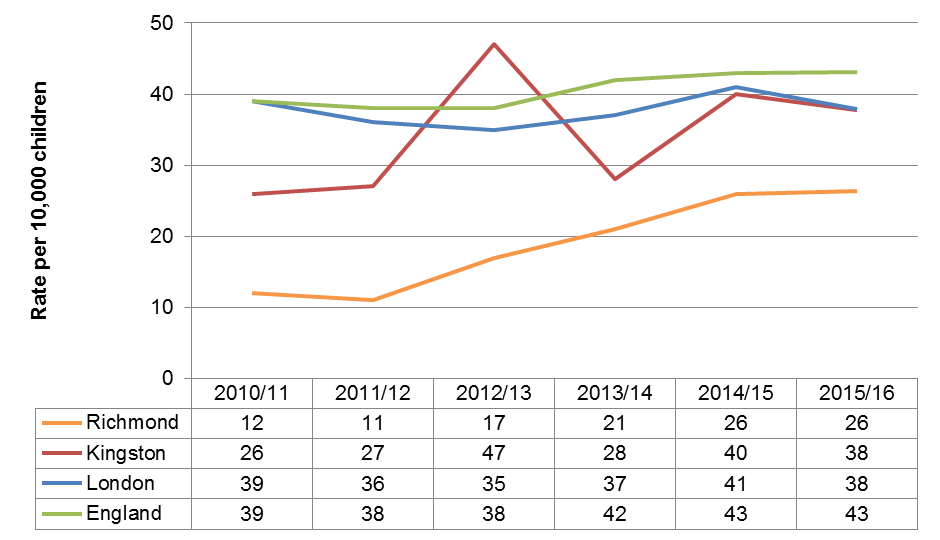

Where concerns about a child’s welfare are substantiated and the agencies involved judge that a child is at continuing risk of significant harm, the child will become the subject of a child protection plan. On 31st March each year, a snapshot is taken of the number of children who are the subject of a child protection plan in each local authority, see Table 3 below. Nationally, there has been an increase in the rate of children on a child protection plan over the past 5 years. However, in Richmond this rate has doubled from 12 to 26 plans per 10,000 children. 117 children were the subject of a child protection plan in Richmond on 31st March 2016.

Table 3 Rate of children who were the subject of a child protection plan at 31 March per 10,000 children

Source: Department of Education 2016 – Statistics: children in need and child protection 4

Looked after children

On 31st March each year a snapshot is taken of the number of children being looked after by each local authority. On 31st March 2016, there were 115 children in the care of Richmond Borough Council. This rate of 26 per 10,000 children is lower than peers in Kingston and Wandsworth, and almost half the London rate (51 per 10,000). The rates of looked after children have stayed relatively stable over recent years but has shown a slight increase in 2016.

Figure 4. Rates of Children looked after at 31 March per 10,000 children aged under 18 years

Source: Department of Education 2016 – Statistics: looked-after children [32]

It is more likely that a looked-after child is male than female, but this likelihood varies across boroughs. On 31st March 2016, 61% of looked-after children in Richmond were male, in Kingston it was 65%. The large majority (83%) of looked-after children in Richmond were over the age of 10 – a larger proportion than comparators.

Table 5 Looked after children, 31st March 2016 by sex and age group

|

|

|

|

|

Age group |

||||

|

|

Total children |

% Male |

% Female |

Under 1 |

1 to 4 |

5 to 9 |

10 to 15 |

≥16 |

|

England |

70,440 |

56% |

44% |

5% |

13% |

20% |

39% |

23% |

|

London |

9,860 |

59% |

41% |

4% |

8% |

14% |

39% |

35% |

|

Kingston |

115 |

65% |

35% |

x |

9% |

19% |

44% |

25% |

|

Richmond |

115 |

61% |

39% |

x |

9% |

6% |

38% |

45% |

X indicates suppression due to small (<5) absolute numbers

Source: Department of Education 2016 – Statistics: looked-after children 5

Of the 115 looked-after children in the responsibility of Richmond Council, roughly 80% were placed in care outside the borough. Conversely, 30 children who were not Richmond residents were placed in care in the Borough. In total, 55 children were placed within the borough of Richmond on 31st March 2016, while 90 Richmond children were looked after elsewhere.

Children missing from care

There were 165 children looked after (excluding those only looked after under a series of short term placements) at any time during the year to 31 March 2016. Of these 165 children, 35 children had a “missing incident” during the year, and 30 disappeared more than once. These 35 children triggered 320 “missing incidents” over the year. This 8.9 average number of missing incidents per looked-after child who went missing, is higher than London (4.9 incidents) and other peers, with Kingston lowest (7.6 incidents.)5

Children living in temporary accommodation

Households that include dependent children or a pregnant woman are considered ‘priority need groups’ for housing and the local authority must ensure that suitable accommodation is available until a settled housing solution becomes available for them, or some other circumstance brings the duty to an end. In 2015/16, there were 150 households with dependent children living in temporary accommodation in Richmond, with approximately 246 children in these households.

Table 6 Absolute number of applicant households with dependent children 2015/16

|

Richmond |

||

|

Applicant whose household includes dependent children |

1 child |

79 |

|

2 children |

46 |

|

|

3 or more |

25 |

|

|

Total HHs with dependent children |

150 |

|

|

HH incl. a pregnant woman (no other dependent children) |

21 |

|

*Where any quarterly values were <5, assumed 2 for ease of summation

t With no other dependent children

Source: Department for Communities and Local Government 2016, Homelessness Statistics [33]

Lacking data

Two risk factors in social services on which there is an insufficient amount of information is young carers and children with a history of abuse. According to the 2011 census, 5% of carers (864 people) are younger than 25 years. Given the sensitivity of the information, it is difficult to estimate the number of children with history of abuse.

4.3. Health Services

Rates of conception

Children with repeat unwanted pregnancies may have been at risk of CSE. Data is available up to 2013 on rates of teenage conception, but not on repeat pregnancies. The percentage of conceptions ending in abortion is available for under-18s in Table 7 below. Given that conception in under-16s in Richmond are so low, the percentage of conceptions leading to abortion cannot be disclosed.

Table 7 Teenage conception rates per 1,000 2011 – 2015

|

|

Area Name |

England |

London |

Kingston |

Richmond |

|

2011

|

U-16 |

6.1 |

5.7 |

4.3 |

4 |

|

U-18 |

30.7 |

28.7 |

22.1 |

19.8 |

|

|

U-18 % abortion |

49% |

61% |

64% |

60% |

|

|

2012 |

U-16 |

5.6 |

4.4 |

5.2 |

2.8 |

|

U-18 |

27.7 |

25.9 |

20 |

19.9 |

|

|

U-18 % abortion |

49% |

62% |

75% |

66% |

|

|

2013 |

U-16 |

4.8 |

4.3 |

2.6 |

2 |

|

U-18 |

24.3 |

21.8 |

15.8 |

11.7 |

|

|

U-18 % abortion |

51% |

64% |

67% |

53% |

|

|

2014 |

U-16 |

4.4 |

3.9 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

|

U-18 |

22.8 |

21.5 |

15.3 |

12.6 |

|

|

U-18 % abortion |

51% |

64% |

79% |

64% |

|

|

2015 |

U-16 |

3.7 |

3.2 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

|

U-18 |

20.8 |

19.2 |

14.1 |

12.9 |

|

|

U-18 % abortion |

51% |

63% |

80% |

82% |

Source: Conceptions in England and Wales Statistical bulletins [34]

As documented in Table 7 above, in 2013, rates of conception in under-16 year olds were low in Richmond at only 2 per 1,000 female population aged 13-15. This is less than half the London rate and lower than comparator boroughs and has been decreasing over recent years. The rate of under-18 conception is 11.7 per 1,000 female population aged 15-17. Again, this is lower than London and comparator boroughs. The proportion of teenagers who aborted their pregnancy decreased in 2013, compared to 2012.

Conception in under- 18 and under-16 year olds is correlated to deprivation nationally. Richmond is one of the least deprived local authorities in England and is the least deprived of all the 33 London boroughs. There are no areas in the borough ranked in the 10% most deprived areas in England. However, there are small pockets of deprivation across the borough and one small area, in the ward of Hampton North in the far south west of the borough, falls into the second 20% most deprived small areas in England. There are concentrations of relatively deprived areas in the wards of Hampton North, Heathfield and Barnes.[35]

Children with repeat sexually transmitted infections

Aggregate data on the number of sexually transmitted infections in Richmond in the 5 years to September 2016 can be seen in Table 8 below. During that period, the numbers of boys aged under 16 diagnosed with Chlamydia and other STIs were fewer than five. Twenty girls under the age of 16 were diagnosed with an STI during the period – an average of four cases per year. Information on repeat STIs were not available.

Table 8 Number of STIs treated in under 19s, 01/10/2011 to 30/09/2016

|

Age |

Chlamydia |

Other STIs (Gonorrhoea, Herpes, Syphilis & Warts) |

||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

<16 |

<5 |

14 |

<5 |

6 |

|

16-19 |

58 |

210 |

63 |

132 |

Source: PHE 2016, HIV & STI Web Portal[36]

Children with poor mental health

It is estimated that there were 1,940 children aged 5-16 with a mental health disorder in Richmond in 2014. Prevalence varies by age and sex, with boys more likely (11.4%) than girls (7.8%) to have experienced or be experiencing a mental health problem. Children aged 11 to 16 years olds are also more likely (11.5%) than 5 to 10 year olds (7.7%) to experience mental health problems.[37]

It was estimated that up to 10,465 children and young people may experience mental health problems appropriate for a response from CAMHS.

Table 9 Estimated number of children / young people who may experience mental health problems appropriate for a response from CAMHS

|

Tier 1: provided by non-mental-health professionals e.g. GPs, school nurses, social services, teachers |

6560 |

|

Tier 2: provided by specialist trained mental health professionals e.g. clinical child or educational psychologists, paediatricians |

3060 |

|

Tier 3: provided by a multidisciplinary team, aimed at young people with more complex mental health problems |

810 |

|

Tier 4: specialised services aimed at children and adolescents with severe and/or complex problems |

35 |

|

Total |

10465 |

Source: CAMHS Needs Assessment 10

Children who self-harm

The rate of hospital admissions for young people following self-harm is higher in Richmond than in peer boroughs or London and has increased over the past few years.

Figure 5. Hospital admissions following self-harm per 100,000 population aged 10-24 years

Source: CHIMAT 2015, Hospital admissions following self-harm[38]

Drug and alcohol abuse

In 2015 a national survey of the health behaviours of 15 year olds was undertaken. The survey showed that 15 year olds in Richmond engage in significantly more risky behaviours (smoking, alcohol and drug use) compared to their peers. 6% of young people in Richmond are regular drinkers and 24.5% reported being drunk in the last 4 weeks, the highest percentage in all boroughs in London. 19% of young people in Richmond reported having ever tried cannabis compared to the London value of 10.9%. This was the highest percentage in London, and third highest in England. 8.5% of young people had taken cannabis in the last month, the highest in London, and compares to 4.6% in England. Richmond had the highest percentage of young people engaging in 3 or more risky behaviours (21.5%) compared to 10.1% in London.[39]

The rate of children being admitted to hospital due to alcohol specific conditions has been falling over recent years and equates to around ten children admitted per year. The 2012/13 – 2014/15 rolling average shows Richmond to have admission rates lower than Wandsworth and Kingston as well as nationally and regionally.

Table 11 Under 18s admitted to hospital due to alcohol specific conditions, crude rate per 100,000 population

|

2006/07 – 2008/09 |

2007/08 – 2009/10 |

2008/09 – 2010/11 |

2009/10 – 2011/12 |

2010/11 – 2012/13 |

2011/12 – 2013/14 |

2012/13 – 2014/15 |

|

|

England |

68.4 |

63.3 |

56.9 |

52.2 |

44.9 |

40.1 |

36.6 |

|

London |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

26.6 |

23.7 |

|

Wandsworth |

39.4 |

50.5 |

43.0 |

43.2 |

41.2 |

35.7 |

33.2 |

|

Kingston |

40.9 |

31.0 |

28.5 |

NaN |

28.4 |

31.6 |

25.1 |

|

Richmond |

47.0 |

43.8 |

42.3 |

42.4 |

39.1 |

27.1 |

18.7 |

Source: PHE Child Health profiles 2017 [40]

Parental substance abuse

Available data on parental substance abuse is available only in the form of those attending treatment, which is not a measure of the number of substance or alcohol misusing parents in an area. Furthermore, the data is somewhat out of date and the most recent is 2012/13.

Table 12 Parents who are attending treatment for substance misuse, who live with their child, rate per 100,000

|

2011/12 |

2012/13 |

2011/12 |

2012/13 |

|

|

England |

110.40 |

107.40 |

147.20 |

145.90 |

|

Wandsworth |

N/A |

53.40 |

150.40 |

139.10 |

|

Kingston |

78.90 |

38.20 |

69.10 |

86.10 |

|

Richmond |

35.00 |

49.80 |

105.10 |

89.20 |

Source: CHIMAT 2015c[41]

Lacking information

If a child presents at A&E with unexplained or sexual injuries this could be a sign of sexual exploitation. It is difficult to identify such cases in the data, but should be recognisable to emergency staff who treat the child. Further current data on parental mental health issues and substance abuse , held by the South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust, may be a further source of data.

4.4. Education Services

It is worth noting that there is quite a lot of migration of the school population between borough borders. In 2014 there were just over 18,000 children living in Richmond: 1,828 of these went to primary, secondary and special schools outside the Borough of Richmond and 4,121 children resident in other boroughs came to school in Richmond

Children missing from school

Data on pupil absence is only available for state-funded schools. In state-funded primary schools, there were 84 unauthorised absences in Richmond in 2015/16. This rate of 6 absences per 1,000 pupil enrolments was lower than comparison regions. At secondary school level, however the rate of 10 unauthorised absences per 1,000 pupil enrolments was higher than Kingston and Wandsworth, but just lower than London and England. Although this does not necessarily mean that a child is missing, it is notably harder to ascertain whether a child is missing if they are on a reduced timetable, excluded or home schooled.

Table 13 Unauthorised absences per 1,000 pupil enrolments, state funded schools

|

State-funded primary schools |

|

|

|

||

|

|

2012/13 |

2013/14 |

2014/15 |

2015/16 |

|

|

|

Unauthorised absences per 1,000 pupil enrolments |

Numbers 2015/16 |

|||

|

England |

7 |

7 |

7 |

8 |

30226 |

|

London |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

5395 |

|

Wandsworth |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

144 |

|

Kingston |

5 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

80 |

|

Richmond |

6 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

84 |

|

State-funded secondary schools |

|

|

|

||

|

|

2012/13 |

2013/14 |

2014/15 |

2015/16 |

|

|

|

Unauthorised absences per 1,000 pupil enrolments |

Numbers 2015/16 |

|||

|

England |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

33742 |

|

London |

12 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

5189 |

|

Wandsworth |

8 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

80 |

|

Kingston |

6 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

55 |

|

Richmond |

11 |

12 |

11 |

10 |

78 |

Source: Department of Education 2016[42]

Children with special educational needs/learning disabilities

A relatively low proportion of children have special education needs in schools in Richmond. However, there is a large absolute number of children: 4,500 in 2016.

Table 14 Number of pupils in all schools with Special Educational Needs (SEN)

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

Richmond |

3,913 |

3,985 |

4,160 |

4,345 |

4,549 |

4,216 |

4,500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Department of Education[43]

Lacking information

4.5. Police

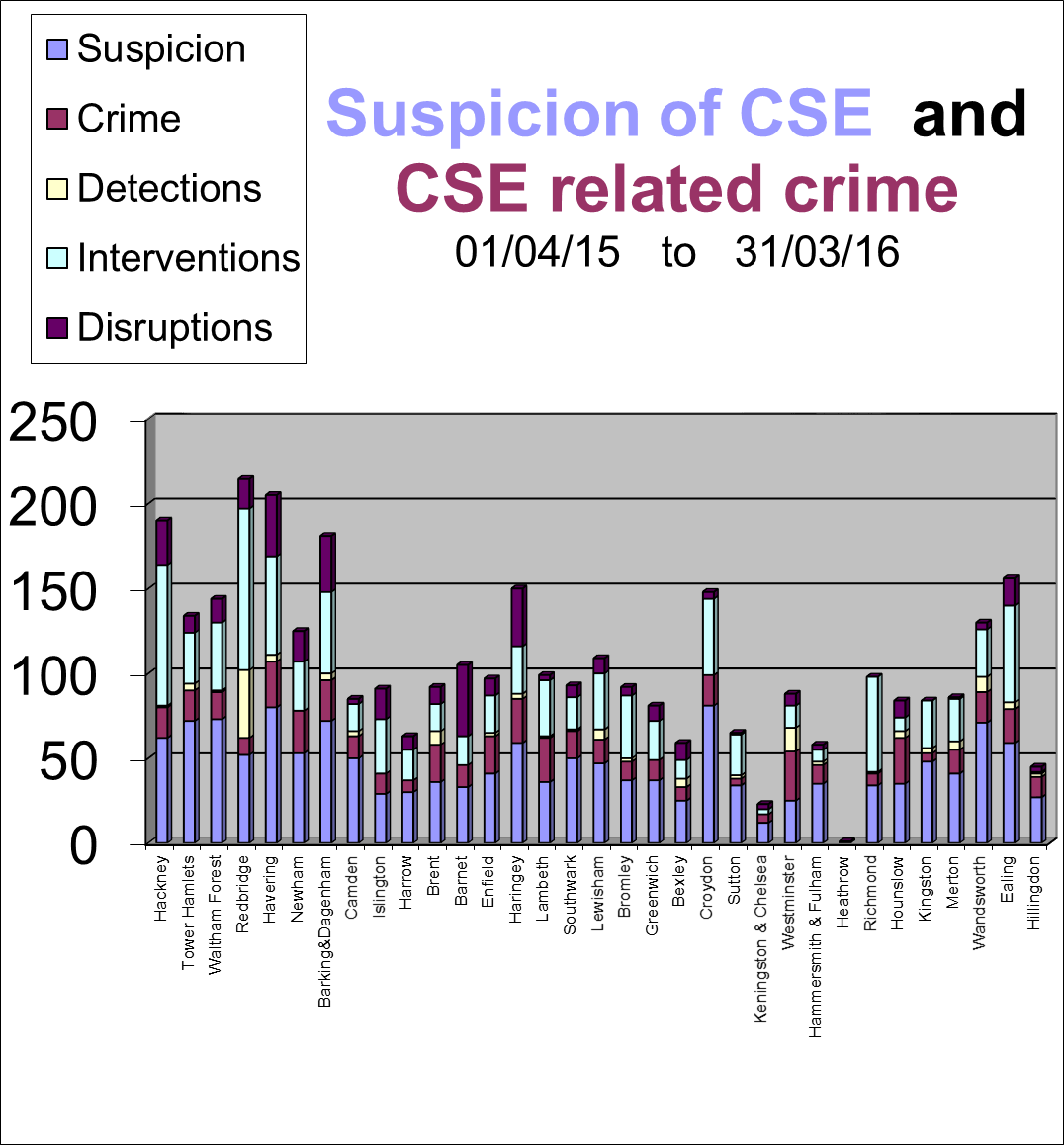

While population level data is available for health and social care statistics, this is more difficult to obtain for police information. This is mostly due to the sensitivity of the information and only authorised individuals can access the data.

There have been a number of CSE cases in Richmond over the past year. The official statistics are not available, but it appears that the victims have been predominantly female, and of white ethnicity. Roughly half were aged 15-17 and the other half were aged under 14.

Figure 6. Suspicion of CSE and CSE Related Crime 2015/16

Source: Crime Reporting System, in Kingston CSE JSNA Chapter Needs Assessment 2015/16

Children missing from home

There were 194 incidences of children reported missing from home in 2015/16, linked to 115 individual children. The majority of incidences (72%) were a direct result of children pushing boundaries, arguing with parents or the child coming home very late. 5.6% were due to the child’s mental or emotional wellbeing.[44]

Children involved in offending

Statistics on children involved in offending are collected for Kingston and Richmond together since Kingston upon Thames Youth Offending Service and Richmond upon Thames Youth Offending Team formally merged into a shared service in June 2013. In the year ending, March 2016 there were 146 proven offences by young people. A proven offence is defined as an offence which results in the offender receiving a reprimand, warning, caution or conviction. Overall, there has been a decrease in the rates of children offending. The boroughs of Kingston and Richmond combined have lower rates of young offending than Wandsworth or London.

Table 15 Rate of proven offences per 1000 of 10-17 population

|

2010/11 |

2011/12 |

2012/13 |

2013/14 |

2014/15 |

2015/16 |

||

|

Kingston & Richmond |

18 |

16 |

14 |

11 |

10 |

5 |

|

|

Wandsworth |

60 |

29 |

24 |

24 |

19 |

18 |

|

|

London |

35 |

28 |

18 |

19 |

18 |

18 |

|

|

E&W |

33 |

26 |

19 |

18 |

17 |

15 |

|

Source: Youth Justice Statistics, 2016[45]

Domestic violence

In 2015/16, 165 children lived with clients in contact with the Richmond Refuge domestic violence outreach service and 200 children lived with clients in contact with the Richmond Refuge Independent Domestic Violence Advocacy service for high risk abuse.[46] In 27% of the most serious cases of domestic violence, victims had mental health support needs and in 22% the perpetrators had mental health support needs.[47]

Richmond has the lowest domestic abuse incident rate in London with 10 offences recorded per 1,000 population in the 2015 calendar year. This compared to 13 in Kingston and 14 in Wandsworth. The highest domestic abuse incident rate was 28 per 1,000 population in Barking and Dagenham.

Table 16 Absolute number of domestic abuse offences per calendar year

|

2012* |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

|

Richmond |

680 |

661 |

821 |

1023 |

1088 |

|

*From March 2012 to year end. Source: MOPAC 2015 – Domestic and Sexual Violence Dashboard; Met police crime 2016/17 [48] |

|

||||

Parental criminality

In 2012, the Ministry of Justice undertook a survey on prisoners’ family backgrounds and found that 54% of prisoners surveyed nationally had children under the age of 18 at the time they entered prison, with an average 2.1 children.[49] This data is not available at a local borough level.

Gang involvement

Either living in a gang neighbourhood or having a gang association either through relatives, peers or intimate relationships puts children at risk of sexual exploitation. Neither Richmond nor Kingston are identified as areas with a gang problem, but 20 other London Boroughs are, including neighbouring Wandsworth, Hammersmith & Fulham and Merton.[50]

Children who have been trafficked, either into or within the UK

No children were recorded as having been trafficked to the UK. At the end of the 2015 financial year, there were 20 unaccompanied asylum seeking children looked after in Richmond.[51] Given Richmond’s proximity to Heathrow, this could be an area for concern.

Evidence of sexual bullying and vulnerability online

Principal risks to children online include: bullying, exposure to sexual images, receiving sexual images and ‘sexting’ and meeting online contacts offline.[52] It is difficult to capture the extent of this conduct.

Lacking information

Recruiting others into exploitative situations – anecdotal evidence to suggest that children/siblings recruit from care homes: turning children against staff and parents and bringing into exploitative situations. Underage sexual activity/inappropriate sexualised behaviour is also a risk factor, but again difficult to quantify.

4.6. Other risk factors

There are a range of other risk factors that are useful to professionals who have regular contact with children to recognise any warning signs, but cannot easily be quantified. Distrust of authority figures and resistance to communicating with parents, carers, teachers, social services, health, police etc. is seen as a warning. Recent bereavement or loss; Unsure about their sexual orientation or unable to disclose sexual orientation to their families; Lacking friends from the same age group; Change in physical appearance; Low self-esteem, self-confidence; Estranged from their family; Receipt of gifts from unknown sources.

5 Local Services

The local service provision has not been included in this needs assessment.

6 Conclusion

Based on this analysis, the prevalence of some CSE risk factors is relatively low in Richmond. However as previously stated, the data on risk factors is likely to underestimate the true issue of CSE and therefore all risk factors should be carefully considered. Despite Richmond continuing to be an overall safe place for people to live there remain a number of risk factors which should be considered:

- The rate of children in child protection plans has doubled in the past five years.

- The average number of missing incidents per looked after child is relatively high.

- The rate of hospital admissions following self-harm is relatively high in Richmond.

- 15-year-olds in Richmond engage in significantly more risky behaviours compared to their peers.

- While Richmond is an area without any gangs, there are gangs in the bordering boroughs and there is significant migration between borough in school and looked-after children population.

Nationally, the young people who most commonly come to the attention of statutory and non-statutory authorities with regard to CSE are aged 14 or 15, although some victims can be as young as 9 or 10 years old.[53] Indeed, in the Richmond population a number of the known risk factors of CSE accumulate at this age:

- Looked-after children – the largest proportion of looked-after children are in the 10-15 year old age group. In Richmond, 43% of looked-after children are in this age group

- Mental health problems – Children aged 11 to 16 years olds are also more likely (11.5%) than 5 to 10 year olds (7.7%) to experience mental health problems

- Risky behaviours – In 2015 a national survey of the health behaviours of 15 year olds was undertaken. The survey showed that 15 year olds in Richmond engage in significantly more risky behaviours (smoking, alcohol and drug use) compared to their peers.

- Unauthorised absences from school – there is just over double the rate of unauthorised absences in state-funded secondary than primary schools.

However, victims can be younger than this age group and should not be excluded.

90% of the cases of CSE in Richmond were female, but it seems very likely that there is an under-reporting in boys due to a perceived stigma. There are a number of risk factors that are higher in boys than girls

- Mental health – prevalence estimates for mental health disorders in children aged 5 to 16 years nationally show boys are more likely (11.4%) to have experienced or be experiencing a mental health problem than girls (7.8%).

- Looked-after children – in Richmond there are marginally more boys (53%) looked-after than girls.

This report has focused on the children who are deemed at risk. However, there must also be a focus on understanding what types of people sexually exploit children and young people in order to prevent it happening. There is not a lot known about who commits child sexual exploitation and identifying abusers is difficult because:

- data often isn’t recorded or is inconsistent or incomplete

- children often only know their abuser by an alias, or appearance

- victims may be passed between abusers and assaulted by multiple perpetrators

- children are often moved from location to location and abused in each place

- young people may be given alcohol or drugs

- The number of known perpetrators is likely to be far higher than those reported.

The Children’s Commissioner’s study found that: 72% of abusers were male, and the age of abusers ranged from 12 to 75 years. Where ethnic group was recorded, the majority of perpetrators were White and the second largest group were Asian.[54]

7 Recommendations

Key recommendations for this needs assessment:

- Local partners, organisations and services to utilise the risk factor prevalence information to ensure services are targeted and delivered appropriately to all vulnerable and at risk groups;

- CSE Subgroup to use information on best practice to carry out multi-agency assessment of local services and approaches; and

- For CSE Subgroup to consider information gaps within this report and identify the next appropriate steps for action.

References

[1]https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/https://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/geography/products/area-classifications/ns-area-classifications/ns-2011-area-classifications/about-the-area-classifications/index.html

[2] https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/child-abuse-and-neglect/child-sexual-exploitation/what-is-child-sexual-exploitation/

[3]https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/278849/Safeguarding_Children_and_Young_People_from_Sexual_Exploitation.pdf

[4] https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/inquiry-child-sexual-exploitation-gangs-and-groups

[5]https://content.met.police.uk/Article/The-London-Child-Sexual-Exploitation-Operating-Protocol-March-2015/1400022286691/1400022286691

[6]https://www.ceop.police.uk/Documents/ceopdocs/ceop_thematic_assessment_executive_summary.pdf

[7] https://www.barnardos.org.uk/ctf_puppetonastring_report_final.pdf

[8]https://content.met.police.uk/Article/The-London-Child-Sexual-Exploitation-Operating-Protocol-March-2015/1400022286691/1400022286691

[9] https://www.barnardos.org.uk/health_impacts_of_child_sexual_exploitation.pdf

[10] https://paceuk.info/about-cse/the-impact-of-child-sexual-exploitation/

[11]https://content.met.police.uk/Article/The-London-Child-Sexual-Exploitation-Operating-Protocol-March-2015/1400022286691/1400022286691

[12] CSEGG Inquiry (reference supplied previously)

[13]https://content.met.police.uk/Article/The-London-Child-Sexual-Exploitation-Operating-Protocol-March-2015/1400022286691/1400022286691

[14]https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/safeguarding-children-and-young-people-from-sexual-exploitation-supplementary-guidance

[15]https://www.rotherham.gov.uk/downloads/file/1407/independent_inquiry_cse_in_rotherham

[16]https://www.rochdale.gov.uk/council-and-democracy/policies-strategies-and-reviews/reviews/Pages/independent-review-of-cse.aspx

[17]https://www.oscb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/SCR-into-CSE-in-Oxfordshire-FINAL-FOR-WEBSITE.pdf

[18] https://www.gmpcc.org.uk/down-to-business/coffey-inquiry/

[19]From page 68 of the CSEGG Inquiry final report https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/If_only_someone_had_listened.pdf

[20]https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/386598/The_20sexual_20exploitation_20of_20children_20it_20couldn_E2_80_99t_20happen_20here_2C_20could_20it.pdf

[21]https://www.local.gov.uk/documents/10180/6869714/Tackling+Child+Sexual+Exploitation+Resource+for+Councils+20+01+2015.pdf/336aee0a-22fc-4a88-bd92-b26a6118241c

[22]https://content.met.police.uk/Article/The-London-Child-Sexual-Exploitation-Operating-Protocol-March-2015/1400022286691/1400022286691

[23]https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/279189/Child_Sexual_Exploitation_accessible_version.pdf

[24] S:\PH & NHSC\Public Health\Work Topics\CSE\National guidance\Materials and Guidance for schools re CSE – January 2015.docx

[25] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/helping-school-nurses-to-tackle-child-sexual-exploitation

[26]https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/279189/Child_Sexual_Exploitation_accessible_version.pdf

[27] https://www.aomrc.org.uk/dmdocuments/aomrc_cse_report_web.pdf

[28]ONS Subnational population projections for England: 2014-based https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/subnationalpopulationprojectionsforengland/2014basedprojections

[29]Characteristics of children in need: 2014 to 2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/469737/SFR41-2015_Text.pdf

[30] Children’s Legal Centre Child Protection Project https://protectingchildren.org.uk/cp-system/child-in-need

[31] Department of Education 2016 – Statistics: children in need and child protection https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-children-in-need

[32]Department of Education 2016 – Statistics: looked-after children https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-looked-after-children

[33]Department for Communities and Local Government 2016, Homelessness Statistics https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/homelessness-statistics

[34]ONS 2015, Conceptions in England and Wales Statistical bulletins https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/bulletins/conceptionstatistics/previousReleases

[35]London Borough of Richmond upon Thames 2015, The Index of Multiple Deprivation https://www.datarich.info/resource/view?resourceId=556

[36]PHE 2016 HIV & STI Web Portal https://www.hpawebservices.org.uk/HIV_STI_WebPortal/login.aspx

[37]National Child and Maternal Health Intelligence Network (CHIMAT) 2015, https://atlas.chimat.org.uk/IAS/profiles/profile?profileId=34&geoTypeId=

[38] CHIMAT 2015a, Hospital admissions following self-harm in young people (pooled years) https://atlas.chimat.org.uk/IAS/dataviews/view?viewId=450

[39]London Borough Richmond upon Thames 2016, What about YOUth? Survey Newsflash https://www.datarich.info/jsna/newsflash20160107

[40] PHE Child health profiles 2017, Hospital admissions for alcohol conditions https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/child-health/profile/child-health-overview

[41]CHIMAT 2015c, Parents in treatment for drug and alcohol misuse https://atlas.chimat.org.uk/IAS/dataviews/view?viewId=314

[42]Department of Education 2016, Statistics: pupil absence https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-pupil-absence

[43] Department of Education 2016, Statements of SEN and EHC plans: England 2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england-january-2016

[44] Achieving for Children local analysis, 2015/16

[45]Ministry of Justice 2016, Youth justice statistics https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/youth-justice-statistics

[46] Making A Difference: Measuring The Impacts of Refuge’s Services, Richmond Outreach and IDVA, 2015/16.

[47] Richmond Multi Agency Risk Assessment Conference data 2015/16

[48] The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) 2015 – Domestic and Sexual Violence Dashboard; Metropolitan Police Crime 2016/17.

[49] Ministry of Justice 2012, Prisoners’ childhood and family backgrounds Results from the Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction (SPCR) longitudinal cohort study of prisoners https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/278837/prisoners-childhood-family-backgrounds.pdf

[50] Gangs and youth crime, Thirteenth Report of Session 2014–15, House of Commons Home Affairs Committee https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmselect/cmhaff/199/199.pdf

[51]National Crime Agency 2015, Human trafficking https://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/publications/national-referral-mechanism-statistics

[52] UK Council for Child Internet Safety 2013, Children’s Online Activities: Risks and Safety. https://www.saferinternet.org.uk/content/childnet/safterinternetcentre/downloads/Research_Highlights/UKCCIS_Report_2012.pdf

[53]NSPCC Child sexual exploitation, Who is affected? https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/child-abuse-and-neglect/child-sexual-exploitation/who-is-affected/

[54] NSPCC Child sexual exploitations, What is child sexual exploitation https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/child-abuse-and-neglect/child-sexual-exploitation/what-is-child-sexual-exploitation/

[55] https://www.nwgnetwork.org/resources/resourcespublic

Document Information

Published: June 2017

For review: June 2020

Topic lead: Anna Bryden

Appendices

Appendix 1. Pre-screening for Equalities Impact Needs Assessment (EINA)

|

Potential impacts on these characteristics have been identified as arising from the topic of this needs assessment |

|||

|

Tick |

Explanation |

||

|

Equality Act 2010 protected characteristics |

Age |

✓ |

By definition only children are at risk of child sexual exploitation |

|

Sex |

✓ |

Reported cases are predominantly female although it is thought that cases in males are under-reported |

|

|

Race |

✓ |

BME groups may be at greater risk of CSE |

|

|

Disability |

✓ |

Learning disability is a risk factor for CSE |

|

|

Religion & Belief |

✕ |

No evidence available |

|

|

Sexual orientation |

✓ |

LGBT groups may be at greater risk of CSE |

|

|

Gender reassignment |

✓ |

LGBT groups may be at greater risk of CSE |

|

|

Pregnancy and maternity |

✓ |

Repeat pregnancy and abortions can be an indicator of CSE |

|

|

Marriage and civil partnership |

✓ |

CSE can be linked to forced marriage |

|

Appendix 2 ’See Me Hear Me’ strategic and operational framework, three essential sets of questions

Voice of the child

These are the questions that will be in the mind of a victim or potential victim of child sexual exploitation. At whatever level they are working, everyone involved in combating CSE should know who the child or young person is (their identity); what they are thinking; and ensure they have answers to the questions they are asking.

These questions have been compiled with and quality assured by a group of young people all of whom have been victims of sexual exploitation.

|

Voice of the child Children and young people are too often left without help because they are invisible to the agencies charged with their protection. See Me, Hear Me has been developed with the help of young people who have been victims of sexual exploitation The purpose of questions below is to bring their voices right into the heart of all planning and decision-making about child sexual exploitation. Children and young people devised these questions with us and have told us that the answers to all of them are important. |

How to use these questions: • Use them to think both about preventing abuse and responding to children’s needs when they have already been victims of abuse. • Involve them at every stage – when developing your local strategies, when building resilient communities, when taking action to protect an individual child. The questions are not in chronological order. Always start from where the young person is at and tailor your responses accordingly. • You may need to revisit some questions repeatedly. • Always check with the young person – it is their life. |

|

Don’t make assumptions about who I am and what I need • Have you thought about me from the start? • What if I don’t see it as abuse? • Have you asked me what I want done and made sure I have a say? • How are you going to tell me what is likely to happen? • Why are there so many of you involved and talking about me? Have you explained that to me? |

For the LSCB: • Use these questions to evaluate the interagency strategy; to consider information-sharing agreements and engagement with the local community in making children safer. • The child sexual exploitation sub-group in particular should use these questions to guide strategy and ensure the involvement of children and young people • Consider local information for children, their friends and family members so that they know who they can tell and how to access help. For schools and colleges: • Consider whether there is a safe environment and a culture within which children and young people can talk about abuse with someone they trust (Mortimer et al, 2012). • Draw on these questions to consider how the planned curriculum includes ways to help children and young people recognise gender stereotyping, abusive situations, and so address issues of consent and how to develop healthy relationships. For police and CPS: • What do these questions mean for our process? For commissioners of services: • Do we have the right information and do we ask the right questions so we can commission services for addressing the emotional needs and mental health of exploited children and young people? |

|

Help make me safe and stop it happening •How do I know that what you have planned will keep me safe? • Are you going to stick with me? • How do I know I can trust you to help me? • Who is taking the overall charge of helping me? • Are you all working together – I don’t want to keep telling my story over and over? • I don’t know how to talk about what’s happened – how are you helping me do this at a pace that works for me? • What are your plans if I go missing – I may have been abducted? |

|

|

It’s not just me • Others at my school and where I am living are at risk – what are you doing about them? • Have you checked who else may be at risk? • Have you checked whether any of my family or my boyfriend/girlfriend are gang members? • What about my family or friends − what do I tell them, what should they know, are they safe, will they help, will they be OK with me? What are you doing to help answer these questions? |

For all agencies: • Are there specific equalities issues that need to be considered and responded to? • Consider whether and how to provide a safe environment for children to tell. Make sure you understand the recognition and telling framework –children do not describe their experiences in a neat linear fashion. • Consider how best to share information about vulnerable young people and manage the number of people involved in working with them. • Do cross agency prevention strategies address these questions? • What about your children who are out of area – how are they being supported and protected? • Have we mapped all gangs and gang associated girls? For all: • Don’t turn your back, it happens, talk about it. • If the child or young person does not recognise the situation as abuse, consider what to do to help them see it is not acceptable. • Make sure that there is a shared plan you are working on with the young person so they can have a bright future. • Plan ways of engaging with children and young people and getting their feedback on whether prevention and protection processes work for them. |

|

Punish the right people (bringing the perpetrator to justice) • How will you support me if this goes to court? • There are lots of people who have hurt me. What are you doing about them? • Some people who have hurt me are my age. What about them? • So now if you’ve stopped them, what will you do to try to make sure it doesn’t happen again? |

|

|

Don’t think there is a quick fix • Have you helped me understand that it wasn’t my fault? • Are you supporting my family to help keep me safe? • Do I have hope for the future? • Who is going to help me to get on with my life, step by step? • Although things are getting better, I am still fragile. Who will be there for me for as long as I need them? • This shouldn’t happen to anyone- what are you doing to help all children and young people to keep safe? |

Voice of the professional

Working with children who have been sexually exploited is extraordinarily difficult and disturbing work. The Inquiry saw first-hand the huge emotional and psychological toll on those on the frontline who are driven to act by a passionate determination to stop sexual exploitation. Agencies have a responsibility to care for and support the professionals doing this work. The questions make agencies face their responsibilities to their staff for it is through their staff that they meet their responsibilities to vulnerable children and young people. Without the right training and support, frontline staff cannot act effectively.

These questions, and those in Protecting the child (below), have been compiled with the help of key representatives from the police, social care, the voluntary sector, health, education and academia. Their contribution has been invaluable.

|

See Me, Hear Me − Voice of the professional |

How to use these questions: • For planning structures and support at strategic and the individual levels • For managers and practitioners to think about their own needs: feeling, reflecting and acting • For managers to consider how they can support and enable their staff |

|

Getting support and staying strong: • This work is stressful – how do I manage the impact on me? • I need time to reflect − can I get help with this? • Can I ask for support without being seen as weak? • Is there support available for me without me needing to ask? • I cannot face doing this work any longer – how do I stop it affecting my personal life? |

For example: • Do practitioners and managers in all agencies have the type of supervision which helps them deal with the impact of this work? • Are managers trained to provide effective case management and reflective supervision? |

|

Trustworthy management • Am I being given the time I need to see and get to know this child? • Is there a strategic vision which supports my work? • What can I expect from my managers to support me? • Will my managers help me to make good decisions? • Will my managers back me when I need to make difficult decisions? |

For example: • Is there a framework of policies and structures in place to support and guide staff and do they know about them? |

|

Being curious about the child • Have I noticed everything I need to notice? • Could I have missed anything? • What is this young person’s behaviour telling me? |