1 Executive Summary

This needs assessment report sets out the current and future challenges that require action to prevent and reduce the prevalence and impact of loneliness and isolation in Richmond. It is intended to inform the policies, strategies, development and commissioning plans, and practice in local organisations.

The terms ‘loneliness’ and ‘isolation’ are often used interchangeably. However, as described below, they are in fact, distinct concepts.

- Isolation refers to separation from social or familial contact, community involvement, or access to services.

- Loneliness refers to a lack of satisfying or rewarding relationships, and relates to how isolation may make someone feel.

The report is based on consideration of research, policy, and guidance; information on Richmond’s population and services; and on the findings of engagement exercises with the local community.

Recognition of the impact of social isolation and loneliness on physical and mental health and wellbeing has increased in recent years, and tackling the issue is currently a high government priority. It is acknowledged that both formal services (e.g. day care centres) and community assets (e.g. neighbourhood associations, lunch and hobby clubs) can contribute to preventing and reducing the impact of loneliness and isolation.

Particular groups are at higher risk of loneliness and isolation. These include older people, people living alone, people with poor health or disabilities, carers, and minority groups.

Richmond’s population has a higher risk of loneliness and isolation, due to the number of older people living alone.

Whilst a number of the Borough’s strategies acknowledge the issue, and a number of existing services targeting particular areas of need, a recent participative asset-mapping project found that the Borough has a range of wider assets that also contribute to reducing risk and reducing the impact of loneliness and isolation. The project concluded that this needs to be more widely recognised, and action taken to tackle barriers to achieve greater contribution from wider community assets.

On this basis there is potential for large-scale change and we should be ambitious in our 2020 vision, and strive towards zero-lonely and zero-isolated neighbourhoods.

The following issues merit further consideration to achieve this.

- How to improve identification of individuals at particular risk of loneliness and isolation by better use of service data and prompt recognition by frontline staff.

- How to improve the targeting and promotion of appropriate services available for those who consider themselves to be lonely and isolated with service providers, including consideration of the provision of information on services and initiatives in appropriate formats.

- Explore the development of local preventive interventions, including life-stage planning for people approaching retirement.

- Consider how Village Plans could be used as a basis for village community initiatives.

- Consideration of approaches to tackle transport barriers for high priority groups.

- Consideration of approaches to further utilise the considerable volunteering ethos and capacity in the Borough.

- Make further links with existing organisations and venues (e.g. education, cultural, faith, etc.), to explore how they can increase what they offer to high risk groups, such as older people.

2 Introduction

2.1. Aim

This needs assessment report sets out the current and future challenges that require action to prevent and reduce the prevalence and impact of loneliness and isolation in Richmond.

2.2. Who is this for?

This needs assessment report is intended to inform the policies, strategies, development and commissioning plans, and practice in local organisations including Council teams, NHS organisations such as the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and Trusts, and other organisations, such as the voluntary sector and representatives of the public and patients.

3 Background

3.1. Context

Recognition of the impact of social isolation and loneliness has increased in recent years, and tackling the issue is currently a high government priority. As a result the issue is reflected in the content of the Care and Support White Paper[1], and the Adult Social Care Outcomes Framework[2] now includes the following considerations.

People are able to find employment when they want, maintain a family and social life and contribute to community life, and avoid loneliness or isolation.

Locally, as part of its work on the joint health and wellbeing strategy, the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames has identified loneliness and isolation as a key issue for older people and a priority for its public health work.

As part of this, a briefing paper from the Public Health Department was presented to the Health and Wellbeing Board, recommending that they consider:

- What further opportunities are there to strengthen integration across the health and social care system, including the third sector, to address the issue of loneliness and isolation amongst older people?

- How can the Health and Wellbeing Board gain commitment from the council, clinical commissioning group (CCG) and other partners that they will consider the potential impact on social isolation when implementing strategies or policies?

As a result it was agreed that this needs assessment be undertaken to better understand the size of the problem locally, current local services and community assets, and identify gaps in service provision in relation to loneliness and isolation.

3.2. Methods and sources

By virtue of the nature of the topic, loneliness and isolation is challenging to enumerate and research. Consequently it is necessary to adopt a mixed methods approach, including the consideration of:

- International and national research, policy and guidance (Chapter 3).

- Local data on demography and health outcomes in London and Richmond (Chapter 4).

- Findings of engagement initiatives with older people in local communities, including workshops (see Appendix 1) and a peer to peer participatory research exercise, adopting an asset-based mapping approach (Chapter 5).[3]

3.3. Definitions and characteristics

3.3.1. Loneliness and isolation

The terms ‘loneliness’ and ‘isolation’ are often used interchangeably. However, as described below, they are in fact, distinct concepts.

- Isolation refers to separation from social or familial contact, community involvement, or access to services.

- Loneliness refers to a lack of satisfying or rewarding relationships, and relates to how isolation may make someone feel.

Loneliness has also been defined as:

“An individual’s subjective evaluation of his or her social participation or social isolation, and is the outcome of having a mismatch between the quantity and quality of existing relationships, on the one hand, and relationship standards on the other.” [4]

In the past, social isolation has been simply defined as the absence of social contacts.[5],[6],[7] This is limited because it assumes that all social contacts have the same function, provide the same support and have the same value. However, it can also be recognised that social isolation actually incorporates a number of different aspects. For instance, a person may have a large number of social contacts, but if they are brief and cursory, they might still be isolated; and extended and meaningful contact with only one individual might well mean that a person is not isolated at all.

3.3.2. Health assets

Community health assets are acknowledged as a source of substantial potential source of support in the prevention and management of loneliness and isolation.

Health assets can be defined as:

“any factor or resource which enhances the ability of individuals, communities and populations to maintain and sustain health and well-being. These assets can operate at the level of the individual, family or community as protective and promoting factors to buffer against life’s stresses.” [8]

Examples of community health assets relevant to loneliness and isolation include:

- Neighbourhood associations

- Lunch clubs

- Recreation and social clubs

- Befriending schemes

- Community centres

- Community transport schemes

3.4. Risk factors

3.4.1. Overview

Research suggests that risk factors for loneliness and isolation include the following characteristics:

- Being aged 75 years and over.

- Living alone.

- Becoming a carer or giving up caring.

- Poor health or disability.

- Living in a deprived area.

- Belonging to minority groups, such as in terms of ethnicity or sexual orientation.

3.4.2. Older people

Loneliness may develop as a chronic state, progressing with age, or occur at a particular time in the life course as a consequence of life events. Older people are particularly vulnerable to social isolation or loneliness owing to loss of friends and family, mobility or income. Many people assume caring roles in midlife and older age, and the stress associated with providing care, including for someone with dementia, can result in high levels of psychological distress. Being a carer can also restrict the ability to participate in social activities (as well as paid employment), with consequences for physical and mental health.

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing also noted that the proportion experiencing loneliness was highest in those over the age of 80.[9]

3.4.3. Minority ethnic groups

In a recent report from Brunel University, levels of loneliness were reported to be higher among ethnic minority elders (aged 65 or over) compared with the rest of the same age population.[10] The same report also notes that although ethnic minority older groups had a wide social network and large household sizes, only 44% reported taking part in social activities that they enjoyed, compared with 79% in the general population. Also, only 55% report that they have someone who gives them love and affection, compared with 88% for the general population.[11]

The situation varies according to the ethnic population concerned. In the Brunel study, only 7% of Indian elders report feeling lonely, whereas 24% of the Chinese population report feeling lonely. The study also found that levels of loneliness were similar to those reported for the same age cohort in the countries of origin. Younger people in ethnic minority groups report lower levels of loneliness than older people. Overall, these studies suggest that living with one’s children and extended family will not necessarily alleviate loneliness.

3.4.4. Sexual orientation

In a report produced by Stonewall, it was noted that gay men and lesbians aged over 55 were less likely to have close social and personal relationships compared with their heterosexual counterparts.[12] For instance, gay men were much less likely to be in a relationship. Lesbians, transsexuals and gay men were also much more likely to live alone, compared with heterosexual people. They were also only half as likely to be living with their children or other family members. Lesbian and bisexual women, and gay and bisexual men, were also much less likely than heterosexual men and women to have children. They were also much less likely to be in contact with members of their biological family.

Gay men, lesbians and bisexuals are more likely to drink more, take drugs and have mental health issues than their heterosexual counterparts. These and the factors listed above suggest that, as they age, gay men, lesbians and bisexuals are at particular risk of being lonely and isolated compared with heterosexual men and women.

3.4.5. Dementia

Although it is not suggested that loneliness causes dementia, there is evidence that it is associated with, and can be predictive of, dementia. For instance, a recent Dutch study [13], found that in a cohort of 2,173 seemingly unaffected community-living older persons, feelings of loneliness were predictive of dementia occurring three years later, independent of other factors such as cardiovascular disease. There was a suggestion that feelings of loneliness might signal a ‘prodromal stage of dementia’.

In a recent report by the Alzheimer’s Society [14], it was observed that:

- One third of people with dementia live alone.

- 29% see friends and family once a week or less.

- 23% expect only one weekly telephone call.

- A third of people with dementia said they lost friends following a diagnosis.

- More than a third (39%) of people with dementia responding to the survey said they felt lonely. Only a quarter (24%) of over-55s in the general public said they have felt lonely in the last month.

- Nearly two-thirds (62%) of people with dementia who live on their own said they felt lonely. Difficulties in maintaining social relationships and other features of dementia contributed to this. The same report also noted that the actual situation is likely to be worse, as dementia is generally under diagnosed and the people who were included in this research did have a diagnosis and had come to the attention of services.

3.4.6. Income

There is evidence that in older people, there is a strong relationship between income and loneliness. In the 2004 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing [15], which looked at people aged 50 years and over, it was noted that there were pronounced inequalities in levels of loneliness in people aged 52 to 59 years, in that those in the lowest economic quintile reported much higher levels of loneliness than those in the next quintile. For the succeeding quintiles, the differences were less marked, but there was a reliable negative relationship between wealth and loneliness. The overall relationship was maintained for those who were aged 60 to 74 years, and those who were 75 years and over.

As people aged and became very old, the differences in levels of loneliness related to wealth and poverty became less stark, but nonetheless, better-off old people were less lonely than poorer old people.

3.5. Impact on health and wellbeing

Although the health impacts of loneliness and isolation tend to be considered together, some research suggests they are in fact distinct. For instance, recent British research [16], indicates that social isolation alone, irrespective of other factors (including loneliness), is associated with a range of poorer physical and mental health outcomes, including earlier death.

Both social isolation and loneliness were associated with higher all-cause mortality. However, social isolation was independently predictive of this outcome, whereas loneliness tended to occur in people whose existing health problems were sufficient explanation in themselves. Recently it has been shown that lonely individuals are twice as likely to die prematurely [17].

Socially disconnected and lonely older adults report lower levels of their physical health than others [18]. Loneliness results in increased and earlier use of expensive health and social care resources, and has also been found to be a predictor for the use of accident and emergency services, independent of levels of chronic illness [19].

The health effects of being lonely and isolated are early mortality, functional decline, cardiovascular problems, earlier occurrence of age-related disease, depression, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, more negative and fewer positive emotions, psychological distress, being overweight, reduced capacity for physical activity, and an impaired immune response.

A recent meta-analysis found that people with stronger social relationships had a 50% increased likelihood of survival than those with weaker social relationships. The influence of social relationships on the risk of death are comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality such as smoking and alcohol consumption, and exceed the influence of physical activity and obesity. In fact, the effects of loneliness and isolation have been compared to smoking 15 cigarettes a day [20].

In addition, there is also substantial evidence linking loneliness to mental health problems. Loneliness and isolation have been linked to:

- Depression in middle-aged and older adults, independent of demographic and other factors [21], [22].

- All ages recovered less well from stress and reacted worse to it if they were lonely [23].

In a 2003 study [24], for instance, it was found that, independent of other factors, socially isolated adults reported more problems associated with stress, including poorer quality sleep.

Excessive use of alcohol and loneliness and isolation may also be related. It is suggested that 20% of men and 10% of women aged 65 and over in the UK exceed recommended drinking guidelines [25]. The researchers indicate that those dependent on alcohol feel lonelier than other groups of people. They also note that the degree of loneliness does not appear to be related to the alcohol user’s social situation. The lonely alcohol misuser also seems to be resigned and unable to change the situation. They will also manifest a range of other psychopathologies and will have less supportive social networks compared with people with other illnesses [26].

As recognised earlier, poor health and disability itself may result in loneliness and isolation. For instance, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing found that in those over the age of 52 who reported poor health, 59% said that they felt lonely sometimes or often; compared with 21% for those who reported excellent health [27].

4 Local Picture

4.1. Introduction

The availability of local valid measures of loneliness and isolation is limited, and consequently establishing insight into the full extent of the issue accurately in Richmond upon Thames is challenging. However, the following sections utilise the locally available information to consider the likely characteristics and needs associated with risk of loneliness and isolation in Richmond upon Thames.

4.2. Older people living alone

As outlined earlier, older people living alone are at higher risk of experiencing loneliness and isolation.

Richmond has the highest proportion of people aged over 75 and living alone in London (51% in Richmond vs. 35% for London).

As shown in the table below the majority of older people living alone are female, and it is estimated that the total number of older people living alone is expected to increase.

Table 1: Number and gender of people aged 65+ years living alone, Richmond, 2012-2020

|

|

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2018 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Males aged 65-74 predicted to live alone |

1,340 |

1,440 |

1,500 |

1,560 |

1,560 |

|

Males aged 75 and over predicted to live alone |

1,632 |

1,700 |

1,802 |

1,904 |

2,074 |

|

Females aged 65-74 predicted to live alone |

2,220 |

2,400 |

2,520 |

2,610 |

2,640 |

|

Females aged 75 and over predicted to live alone |

4,636 |

4,697 |

4,758 |

4,941 |

5,185 |

|

Total population aged 65-74 predicted to live alone |

3,560 |

3,840 |

4,020 |

4,170 |

4,200 |

|

Total population aged 75 and over predicted to live alone |

6,268 |

6,397 |

6,560 |

6,845 |

7,259 |

Source: Projecting older people population (POPPI)

A survey of the users of local social care services, many of whom are older people, found that a majority do not have as much social contact as they would like.

These growing numbers of older people will be at increased risk of depression and dementia. Those with limiting long-term illness will be particularly vulnerable.

4.3. Lesbian, gay and bisexual people

Beyond Richmond, surveys found that 1.5% of the national population and 2.5% in London consider themselves LGB and a government report estimated that between 5% and 7% of the population in England and Wales is LGB . A conservative estimate (5%) equates to 9,500 people in Richmond. However, some local organisations suggest an estimate of 10%, equating to 19,000 people, is more realistic.

Three in five are not confident that social care and support services, like paid carers, or housing services would be able to understand and meet their needs.

Also, people in these groups are more likely to rely on formal support services as they get older, due to living alone, and being less likely to have children.

4.4. Carers

The number of carers aged 65 years and over in Richmond and receiving services is estimated to increase from 408 to 497, an increase of 25%. Being an older carer can result in limitations in freedom to leave the home and can result in isolation.

4.5. Sensory disability

The problem of loneliness and isolation associated with loss of hearing could be especially problematic in Richmond upon Thames as the percentage of older people who are registered deaf is nearly three times as high as the national average.

4.6. Income

The older people of Richmond upon Thames are relatively better off than older people in most other parts of the country

Although Richmond is one of the most affluent areas of the country, there are marked variations in levels of affluence within the borough, with clear pockets of deprivation in certain areas.

The wards of Kew, Barnes and Hampton North have the highest estimated numbers of residents aged 85 and over, at around 240 for each of these areas. Kew is an affluent area and Barnes has a mix of affluence and more than average deprivation. Hampton North and Hampton wards both encompass small Lower Super Output Areas (LSOA) of more than average deprivation.

5 Local strategies and services

5.1. Introduction

Loneliness and isolation can be prevented and its impact limited both by direct service provision and wider strategies influencing acknowledged local risk factors. Both these contributions are considered in the following sections.

5.2. Local strategies

The importance of tackling loneliness and isolation in Richmond upon Thames has been acknowledged in numerous influential local strategies, including:

- Health and Wellbeing Strategy [28]

- Better Care Closer to Home: Richmond Out of Hospital Care Strategy 2014 – 2017 [29]

- Annual Public Health Report [30]

5.3. Local services and assets

5.3.1. Introduction

A comprehensive participatory asset-based mapping project, examined the local situation [31],[32].

The project documented current and potential assets, and identified approaches to optimising the contribution that can be made from all asset-classes.

5.3.2. Findings

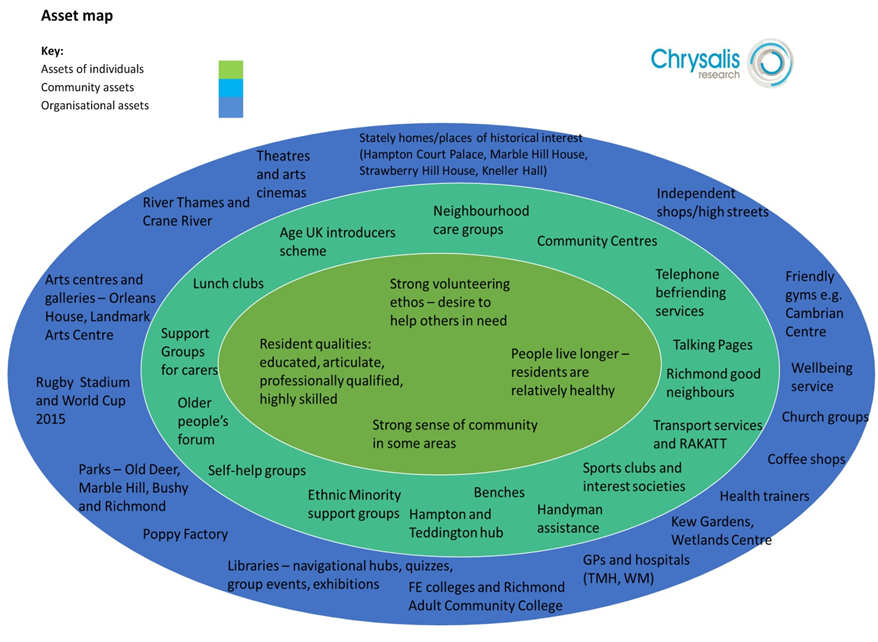

As summarised in the bullets and Figure below, the project reported the following local assets:

- Assets of individuals – e.g. strong volunteering ethos, residents being relatively healthy, educated and highly skilled, and a strong sense of community.

- Community assets – e.g. lunch clubs, neighbourhood care groups, self-help groups and telephone befriending services.

- Assets of organisations – e.g. theatres and cinemas, friendly gyms, church groups, coffee groups and libraries.

Figure 1. Richmond loneliness and isolation asset map

Overall, the work found that Richmond has a wealth of assets to offer its residents that can be harnessed to reduce loneliness and isolation.

Specific current services and initiatives in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames include:

- Befriending services.

- Borough Champion for older residents.

- Introducers’ initiative (i.e. introducing older people to social clubs and activities in their local community).

- Computer facilities for the elderly.

- Physical activity initiatives to promote social networking.

- Age UK Richmond upon Thames manages a number of social clubs and centres for older people.

5.3.3. Overcoming barriers

Despite this healthy stock of local assets, as summarised below, the project also identified a range of barriers to their optimal contribution.

- Low awareness of opportunities and activities available in the Borough.

- Financial barriers for individuals who are on a low income.

- Appropriateness and appeal of services aimed at older people.

- Confidence and companions to attend new places.

- Lack of transport.

- Resistance to change.

- Poor understanding and lack of skills held by service staff.

One of the key barriers cited by participants was the lack of genuine and sustained support for older people to try new activities and attend new venues. The key recommendation made to address this was to create systems of peer support and companionship for individuals who are on their own and would otherwise choose not to go to new places because they lack confidence or have no one to go with.

Workshop participants generated recommendations and actions for overcoming the key barriers, including:

- Dissemination of information and system navigation.

- Peer support.

- Making links with the borough’s village plans.

- Marketing of key assets.

- Improving transport links.

6 Conclusion

Loneliness and isolation has an acknowledged impact on physical and mental health.

Richmond’s population has a higher risk of loneliness and isolation, due to the number of older people living alone.

However, the Borough has some specific strategies which acknowledge the issue, and a number of existing services targeting particular areas of need.

Also, an asset-mapping project found that the Borough has a range of wider assets that also contribute to reducing risk and reducing the impact of loneliness and isolation; but concluded that this needs to be more widely recognised, and action taken to tackle barriers to achieve greater contribution from wider community assets.

On this basis there is potential for large-scale change and we should be ambitious in our 2020 vision, and strive towards zero-lonely and zero-isolated neighbourhoods.

The following issues merit further consideration to achieve this:

- How to improve identification of individuals at particular risk of loneliness and isolation by better use of service data and prompt recognition by frontline staff.

- How to improve the targeting and promotion of appropriate services available for those who consider themselves to be lonely and isolated with service providers, including consideration of the provision of information on services and initiatives in appropriate formats.

- Explore the development of local preventive interventions, including life-stage planning for people approaching retirement.

- Consider how Village Plans could be used as a basis for village community initiatives.

- Consideration of approaches to tackle transport barriers for high priority groups.

- Consideration of approaches to further utilise the considerable volunteering ethos and capacity in the Borough.

- Make further links with existing organisations and venues (e.g. education, cultural, faith, etc.), to explore how they can increase what they offer to high risk groups, such as older people.

References

[1] Department of Health. Caring for our future: Reforming care & support. July 2012

[2]Department of Health. Adult Social Care Outcomes Framework (ASCOF (2013/14)

[3] Chrysalis Research Ltd. (2014) Loneliness and Isolation: An asset based integrated approach to a strategic needs assessment.

[4] Perlman, D. and Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In S. W Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.J , Personal Relationships. 3: Personal relationships in disorder (pp. 31-56). London: Academic Press. https://www.iscet.pt/sites/default/files/obsolidao/Artigos/Loneliness%20and%20Social%20Isolation.pdf

[5] Grenade, L. and Boldy, D. (2008) Social isolation and loneliness amongst older people: issues and future challenges in community and residential settings. Australian Health Review. 2008;32:468–478. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18666874

[6] Hall, M., Havens, B. (2001) The effects of social isolation and loneliness on the health of older women. Research Bulletin, Centres of Excellence for Women’s Health. 2001;2:6–7. Available from https://www.pwhce.ca/effectSocialIsolation.htm

[7] Cattan, M., White M., Bond, J., Learmouth, A. (2005) Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing & Society 25, 2005, 41–67. 2005 Cambridge University Press Available from https://carechat.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/isolation-studies.pdf

[8] Morgan A, Ziglio E. (2007) Reflecting on the Charter’s action areas Revitalising the evidence base for public health: an assets model. IUHPE – Promotion & education supplement 2.

[9] Banks J., Nazroo, J., Steptoe, A. (Eds) (2012) The Dynamics of Ageing Evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing 2002–10 (wave 5) The Institute for Fiscal Studies 7 Ridgmount Street London WC1E 7AE Available from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/pdf/elsa5final.pdf

[10] Victor, C. R., Burholt, V., Martin, W. (2012) Loneliness and ethnic minority elders in Great Britain: an exploratory study. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2012 Mar;27(1):65-78. doi: 10.1007/s10823-012-9161-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22350707

[11] Bowling, A. (2012) ”What do we know about loneliness?” Conference presentation https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org.uk/loneliness-conference/

[12] Guasp, A. (2010) Lesbian, gay and bisexual people in later life. Stonewall https://www.stonewall.org.uk/documents/lgb_in_later_life_final.pdf

[13] Tjalling, J.H., Darley, J.H.D., Aartjan, T.F.B., Tilburg, T.G., Stek, M.L., Jonker, C., Schoevers, R.A. (2012) Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-302755 Available from https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/early/2012/11/06/jnnp-2012-302755.abstract

[14] Kane, M., Cook, L. (2013) Dementia 2013: The hidden voice of loneliness. Alzheimer’s Society. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1677

[15] Demakakos, P., Nunn, S., Nazroo, J. (2006) Loneliness, relative deprivation and life satisfaction. In: Banks, J and Breeze, E and Lessof, C and Nazroo, J, (eds.) Retirement, health and relationships of the older population in England: The 2004 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (Wave 2). (297 – 338). The Institute for Fiscal Studies: London. Available from https://www.ifs.org.uk/elsa/report06/ch10.pdf

[16] Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., Wardle, J. (2013) Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women.Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America. https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/03/19/1219686110.full.pdf+html

[17] Cacioppo JT. (2014). Available online at https://aaas.confex.com/aaas/2014/webprogram/Paper10841.html

[18] Cornwell, E.Y. and Waite, L. J. (2009) Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults’ Health Soc Behav 50(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2756979/?tool=pubmed

[19] Geller, J., Janson, P., McGovern, E., et al. (1999) Loneliness as a predictor of hospital emergency department use. J Fam Pract 1999;48:801e4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12224678

[20] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B., Layton. J.B. (2010) Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLoS Med 7(7): https://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1000316

[21] Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L.C., Thisted, R.A. (2006) Loneliness as a Specific Risk Factor for Depressive Symptoms: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analyses. Psychology and Aging 2006, Vol. 21, No. 1, 140–151. https://psychology.uchicago.edu/people/faculty/cacioppo/jtcreprints/chwht06.pdf

[22] Aylaz, R., Akturk, U., Erci, B., Ozturk, H., Asian, H. (2012) Relationship between depression and loneliness in elderly and examination of influential factors. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics Volume 55, Issue 3 , Pages 548-554, November 2012 https://www.aggjournal.com/article/S0167- 4943(12)00053-2/abstract

[23] Ong, A. D., Rothstein, J. D., Uchino, B. N. (2012) Loneliness accentuates age differences in cardiovascular responses to social evaluative threat. Psychology and Ageing, Vol 27(1), Mar 2012, 190-198. https://psycnet.apa.org/journals/pag/27/1/190/

[24] Cacioppo, J. T. and Hawkley, L. C. (2003) Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003 Summer;46(3 Suppl):S39-52 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14563073

[25] Robinson, S. and Harris, H. (2011) Smoking and Drinking Among Adults, 2009: A Report on the 2009 General Lifestyle Survey. London: Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ghs/general-lifestyle-survey/2009-report/index.html

[26] Akerlind, I., Hornquist, J. O. (1992) Loneliness and alcohol abuse: a review of evidences of an interplay. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Feb;34(4):405-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1566121

[27] Banks, J., Nazroo, J., Steptoe, A. (2012) The Dynamics of Ageing:Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of ageing 2002-10 (Wave 5) Institute for Fiscal Studies https://www.ifs.org.uk/ELSA/reportWave5

[28] Health and Wellbeing Strategy (May 2014) https://www.richmond.gov.uk/health_and_wellbeing_strategy_april_13.pdf

[29] Better Care Closer to Home: Richmond Out of Hospital Care Strategy 2014 – 2017 (January 2014) https://www.richmondccg.nhs.uk/strategies%20policies%20and%20registers/Better_Care_Closer_to_Home_strategy.pdf

[30] The annual report of the Director of Public Health 2014/15. February 2015.

[31] Chrysalis Research. (2014) Loneliness & isolation: An asset-based integrated approach to a strategic needs assessment.

[32] Chrysalis Research. (2014) Addressing loneliness & isolation in Richmond upon Thames: Peer research project findings.

Appendix 1: Organisations and council departments attending workshops

AGE UK

Alzheimer’s Society South West London

AMA UK

Arts Richmond

Barnes, Mortlake and East Sheen FiSH

Castelnau Centre Project

CCGPG Network Group

Councillors Bouchier

Councillor Percival – Chair of Health and Wellbeing Board

Crossroads Care Richmond & Kingston Thames

Elleray Hall Social Club

For Sanity’s Sake

Ham and Petersham SOS Scheme

Hampton & Hampton Hill Voluntary Care

Hampton & Hampton Hill Voluntary Care Group

HANDS (Help a neighbour in need scheme)

Homelink Day Respite Care Centre

Integrated Neurological Services

Inter Faith Forum

Kew Community Trust

Kew Neighbourhood Association

Kingston Advocacy Group

LBRuT, Adult and Community Services

LBRuT, Barnes

LBRuT, Joint Commissioning Collaborative

LBRuT, Public Health

LBRuT, South Richmond

LGBT Forum

Linden Hall Community Centre

LiveWell Richmond

Peer Group Network, Peer Volunteer Manager

RHP

Richmond Aid

Richmond Carers

Richmond Citizens Advice Bureau

Richmond Council for Voluntary Services

Richmond Good Neighbours

Richmond Older Peoples Forum

Richmond Wellbeing Service

RUILS

SSAFA Richmond Upon Thames

Still Building Bridges

The Mulberry Centre

Whitton Network

Appendix 2: Equalities Impact Needs Assessment (EINA)

To be completed for all needs assessments, to provide the foundations for EINAs at the point of service commissioning and strategy development.

|

|

|

Potential impacts on these characteristics have been identified as arising from the topic of this needs assessment |

Do existing services covered in this needs assessment collect monitoring information on any of these characteristics? (Add one column per service) |

Stakeholder groups |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Relevant stakeholder groups identified (Please list) |

How have relevant stakeholder groups been involved in this needs assessment? |

||||

|

Equality Act 2010 protected characteristics |

Age |

✓ |

High impact |

NA |

NA |

See main document |

Yes see main text for engagement section |

|

Sex |

✓ |

High impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Race |

✓ |

High impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disability |

✓ |

High impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Religion & Belief |

✓ |

Impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sexual orientation |

✓ |

Impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender reassignment |

✓ |

High Impact |

no |

no |

|

|

|

|

Pregnancy and maternity |

✓ |

No Impact |

no |

no |

|

|

|

|

Marriage and civil partnership |

✓ |

No impact |

no |

no |

|

|

|

|

Public Sector Equality Duty goals |

Eliminating discrimination, harassment or victimisation |

✓ |

This needs assessment aims to promote and reduce |

|

|

|

|

|

Advancing equality of opportunity between different groups |

✓ |

This needs assessment aims to promote equality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fostering good relations |

✓ |

This needs assessment aims to promote equality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resources: · Richmond health needs assessments on each of the nine protected characteristics of the Equality Act 2010 are available at www.richmond.gov.uk/jsna · Equalities profiles providing Richmond statistics on the nine protected characteristics are available on DataRich https://www.datarich.info/equality-and-diversity |

|||||||

Document Information

Published: March 2015

For review: April 2018

Topic lead: Jane Bailey, Public Health Lead