Introduction

Aim

The purpose of this document is to scope and review cardiology services for Richmond patients. It aims to understand current clinical practice and referral routes for specific cardiology services and conditions, including diagnostics, and paediatric diagnostics. It sets out the local needs, costs, and makes the case for change for improving cardiology services for Richmond patients. The latest guidance, evidence, and best practice have been referenced and incorporated. Recommendations have been put forward to develop cost effective, equitable, and accessible high quality services for our patients.

Who is this for?

A cardiology pathway steering stakeholder group was set up to lead the review with a smaller project working group to identify, understand and map existing services, identify gaps in service provision, identify patient need, define best practice and drive quality and cost efficiencies through service redesign. Both groups were multi-disciplinary, comprising of clinicians from primary and secondary care, commissioners, and public health professionals. The project has been led, coordinated and supported by the Public Health department, with a dedicated public health lead working full time on the pathway review and redesign work.

The steering group met monthly over a 10 month period who delivered a final presentation at the Clinical Advisory Group on 4th March 2014. A smaller project team was set up to undertake the work and met fortnightly. See Appendix 1 for the membership list for the projects team and steering group.

Background

Cardiac Conditions

There are a number of cardiac conditions that a patient can be born with, or may develop over time due to a number of reasons, including:

- Rheumatic heart disease (Valvular heart disease)

- Hypertensive heart disease:

- Aneurysms

- High blood pressure

- Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) also known as Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) – this is caused by the narrowing of the coronary arteries, leading to a decrease of blood supply to the heart.

- Angina

- Inflammatory heart disease:

- Cardiomyopathy

- Pericardial disease

- Congenital heart disease – this term covers various heart defects an individual is born with.

- Heart failure (HF)

- Cerebrovascular heart disease – this is the blood vessels in the brain; blood supply to a part of the brain has been hindered, which causes this disease (TO BE COVERED IN PART 2 OF THE REVIEW).

- Stroke

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Cardiac Arrhythmias – this is irregularities in the heart beat; either beating too slow or too fast.

- Atrial Fibrillation (AF) (TO BE COVERED IN PART 2 OF THE REVIEW)

- Palpitations

- Heart block

- Brachycardias

- Tachycardias

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Long QT syndrome

- Wolff Parkinson White syndrome

Evidence Based Practice

Evidence based practice in health and social care is essential in order to have an integrated approach to deliver the most clinically appropriate, high-quality and safe care by using a combination of current evidence, clinical research, guidelines and policies.

The National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease (Department of Health, March 2000).This NSF sets out twelve service standards that cover the following areas:

- Reducing heart disease in the population

- Preventing CHD in high-risk patients

- Heart attack and other acute coronary syndromes

- Stable angina

- Revascularisation

- Heart failure

The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) have published a number of documents with guidance to reflect good practice at key stages of diagnosis, management and further care for various heart conditions, including:

- NICE Chest pain of recent onset (2010)

- NICE Prevention of cardiovascular disease (2010)

- NICE Unstable angina and NSTEMI (2010)

- NICE TA Implantable cardioverter defibrillators for arrhythmias (2007)

- NCCPC Lipid modification (2010)

- NICE PH25 Prevention of cardiovascular disease (2010)

- MI: secondary prevention in primary and secondary care for patients following a myocardial infarction. (2007)

A number of other professional bodies, organisations and charities have published credible guidelines for the identification, treatment and management of heart diseases including:

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Acute Coronary Syndromes (2012).

- The Health Foundation. Healthcare delivery models for prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Although a wide range of clinical guidance exists for the plethora of heart conditions, there does not appear to be an agreed guide for the general initial investigation of suspected cardiology conditions. However, using a combination of key clinical guidance and primary literature, knowledge can be drawn to determine key best practice methods and diagnostic procedures to identify and investigate a suspected cardiology condition.

Best Practice for cardiology/suspected cardiology at primary care presentation

Best practice guidelines for initially assessing, identifying and managing patients for the common cardiology conditions GPs usually see at primary care.

There are a number of symptoms a patient may present with that is indicative of a cardiology condition. Several symptoms can appear together, or only one may be present at the time of GP presentation[i],[ii],[iii],[iv]:

- Chest pain/discomfort

- Dull pain, ache or ‘heavy’ feeling in chest

- discomfort in the neck, shoulders, jaw, or arms

- Difficulty breathing during regular activities and rest

- Palpitations or heart flutters

- syncope

- dizziness

- sweatiness

- breathlessness/ shortness of breath

- headaches

- transient visual loss

- wheeze

- High BP

- Unexplained indigestion, belching, epigastric pain

- nausea/vomiting,

- back or jaw pain,

- loss of appetite or heartburn,

- tiredness or weakness,

- coughing

As well as assessing the signs and symptoms of a patient, it is essential that the GP takes the history of the patient and identifies any risk factors that would influence the risk of an individual having a heart condition including, but not limited to[v]:

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidemia

- Smoking

- Obesity

- High cholesterol

- Physical inactivity

- Age

- Family history

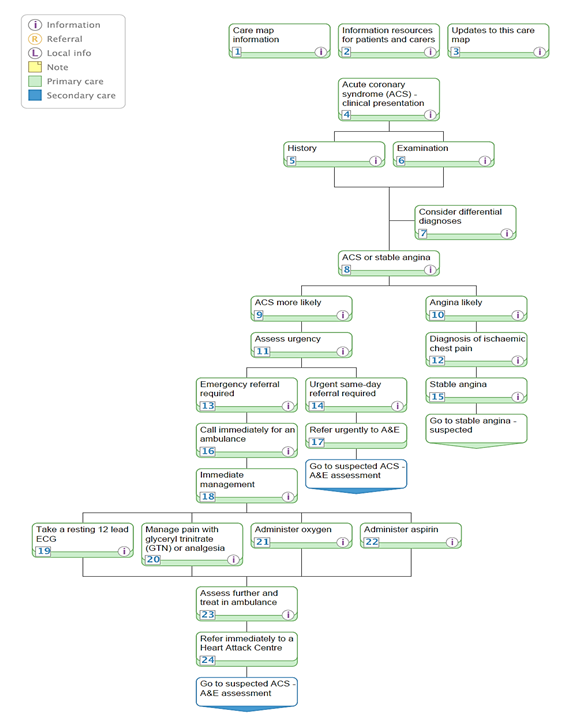

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

ACS is the term used when referring to the family of unstable coronary artery diseases (CAD) ranging from unstable angina to transmural myocardial infarction (MI)[vi] . Most of these diseases have similar aetiology. When a GP suspects a patient may have any of the conditions under ACS, the following should be done[vii],[viii]:

- Take patient history

- Clinical examination (see table 1)

- Assess if patient has any of the risk factors for ACS/CVD and other heart conditions

- 12-lead ECG – this can be repeated if there is diagnostic uncertainty or change in the patient’s clinical status

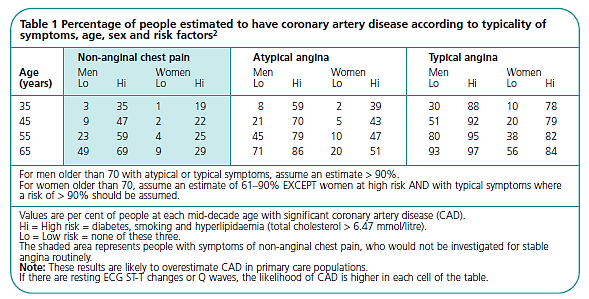

When suspecting CAD, but it is not confirmed and stable angina is nether diagnosed or excluded, the GP should estimate the likelihood of the patient having CAD which can be done using table 2[ix].

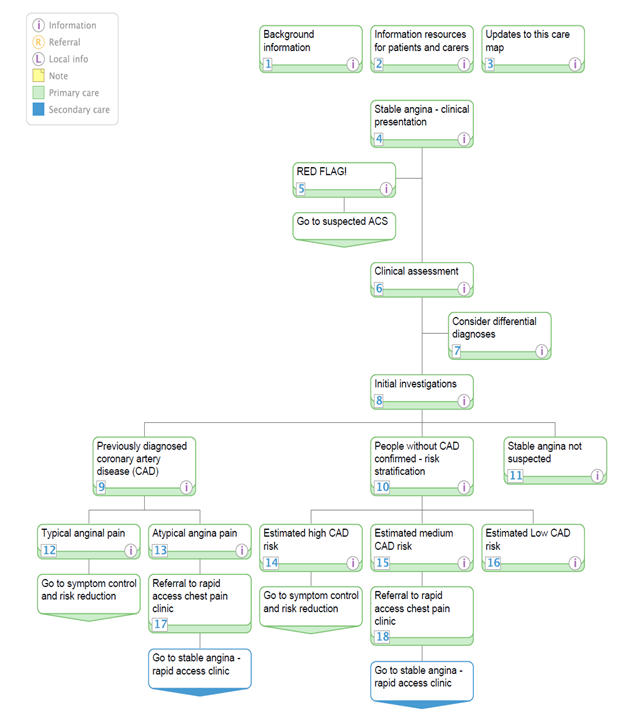

Angina (see appendix 4 for pathway)

Angina is a pain or discomfort in the chest usually caused by CAD; however in some cases the pain may affect some people only in the arm, neck, stomach or jaw[x]. Types of angina include:

- Stable Angina – Constricting discomfort in the front of the chest, in the neck, shoulders, jaw, or arms. It is usually precipitated by physical exertion; the pain usually lasts only for a few minutes.

- Unstable angina (symptoms can manifest in both stable or unstable)– dull/heavy to sharp chest pain or discomfort

- Constricting discomfort or pain in the front of the chest, in the neck, shoulders, jaw, or arms.

For patients with suspected cardiac chest pain, they should be referred to a rapid access chest pain clinic (RACPC).

Unstable angina

When a patient presents with acute chest pain the GP should[xi]:

- Take a resting ECG ASAP – do not exclude an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or assess ACS differently in ethnic groups.

- Monitor oxygen saturation (SpO2) using pulse oxiemtry. Only offer oxygen to people with SpO2 less than 94% who are not at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure (aim for SpO2 of 94–98%) and people with COPD and at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure( aim to achieve SpO2 of 88–92% until blood gas analysis is available).

Diagnosis of stable angina

If a patient presents, do the following:

- Clinical assessment – history and examination (see table 1)

- Clinical assessment and a resting 12-lead ECG ( NB a normal resting 12-lead ECG does not exclude stable angina as a diagnosis)

Once angina has been diagnosed as stable, it can be managed effectively within primary care. For presentation and management of stable angina in primary care (see appendix 4 for pathway).

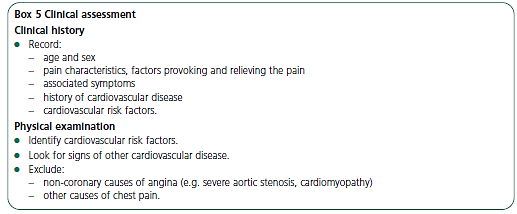

Figure 1 Clinical history and physical examinations that should be performed for patients with suspected or confirmed stable angina

Source: NICE Chest pain of recent ofset (2010)

Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) (also known as Coronary Artery Disease (CAD))

CHD/CAD is the blockage of the bold vessel and Ischaemic Heart Disease (IHD) happens due to the insufficient blood flow to the muscles through the coronary arteries. Angina is usually an indication of CHD.

Table 1 Reference for people estimated to have CAD according to certain factors

Source: NICE Chest pain of recent onset (2010)

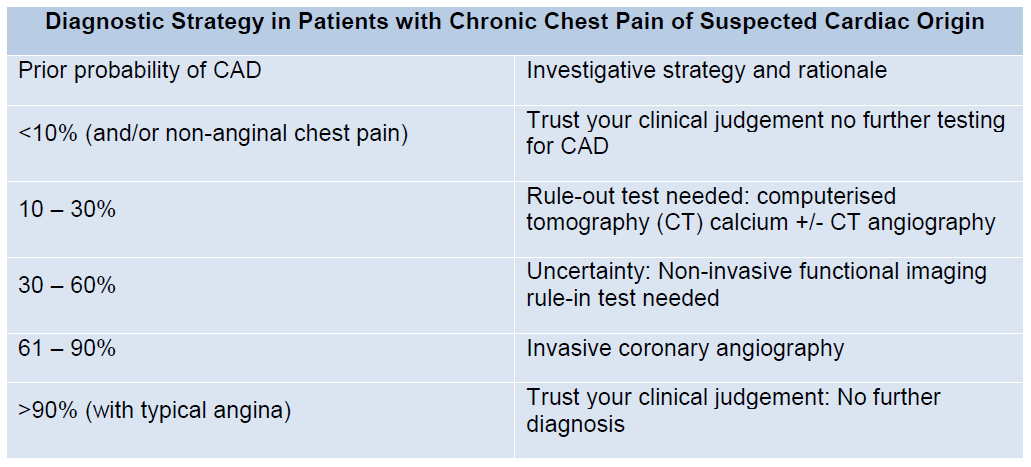

Table 2 Probability table to decide how to refer suspected CAD patients.

Source: Greater Manchester and Cheshire Cardiac and Stroke Network Primary Care Pathways

Both tables should help the GP decide whether to refer patients to the cardiology department.

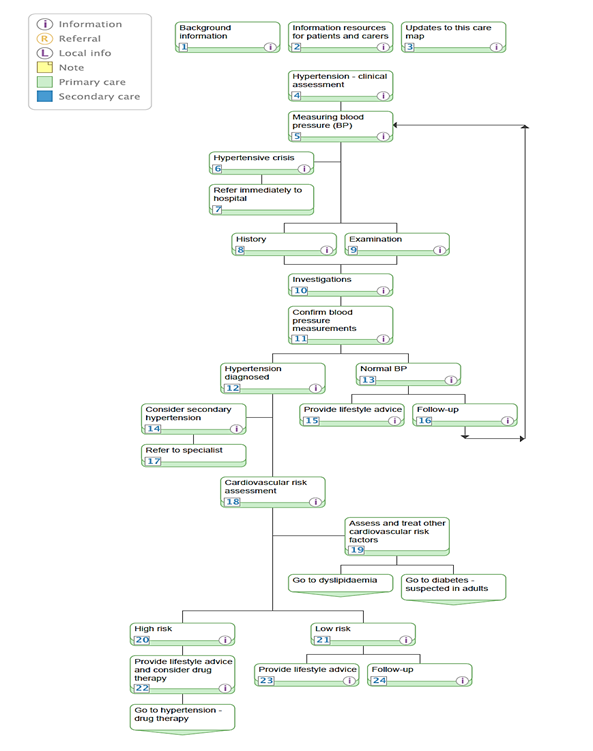

Hypertension

Hypertension is arguably the most important modifiable risk factor for CHD (the leading cause of premature death in the UK). It is also an important cause of congestive heart failure[xii]. In England, 32% of men and 30% of women aged 16 years or over have hypertension (persistent raised blood pressure of 140/90mmHg or above) or are being treated for high blood pressure (BP)[xiii]. This means that, in terms of the average GP’s list of 2,000 patients, about 500 will have hypertension[xiv]. The strong association in the UK between increasing age and increasing systolic BP is thought to reflect the length of time that people have been exposed to modifiable lifestyle risk factors.

N.B. The thresholds for hypertension in people with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes are slightly lower.

If a patient has a BP of 140/90 mmHg or higher, the GP should do the following[xv] as per the NICE guidance:

- Offer ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension

- When using ABPM to confirm diagnosis, ensure that at least two measurements per hour are taken during the person’s usual waking hours (average of 14 measurements during waking hours)

- When using home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, ensure that:

- For each BP recording, two consecutive measurements are taken, at least 1 minute apart and with the person seated, and

- BP is recorded twice daily, ideally in the morning and evening and

- BP recording continues for at least 4 days, ideally for 7 days.

- NB: Discard the measurements taken on the first day and use the average value of all the remaining measurements to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension.

Whilst waiting to confirm the diagnosis of suspected hypertension, GPs should carry out investigations for target organ damage and a formal assessment of CVD risk:

- Use estimation of CVD risk to discuss prognosis and healthcare options with people with hypertension

- Assess target organ damage:

- Test for protein in the urine (albumin: creatinine ratio) and test for haematuria.

- Take blood sample to measure plasma glucose, electrolytes, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol.

- Examine the fundi for the presence of hypertensive retinopathy.

- Arrange for a 12-lead ECG.

Refer people to specialist care on the same day if they present with:

- Accelerated hypertension (BP higher than 180/110 mmHg) with signs of papilloedema and/or retinal haemorrhage, or

- Suspected phaeochromocytoma (labile or postural hypotension, headache, palpitations, pallor and diaphoresis).

- People with signs and symptoms suggesting a secondary cause of hypertension.

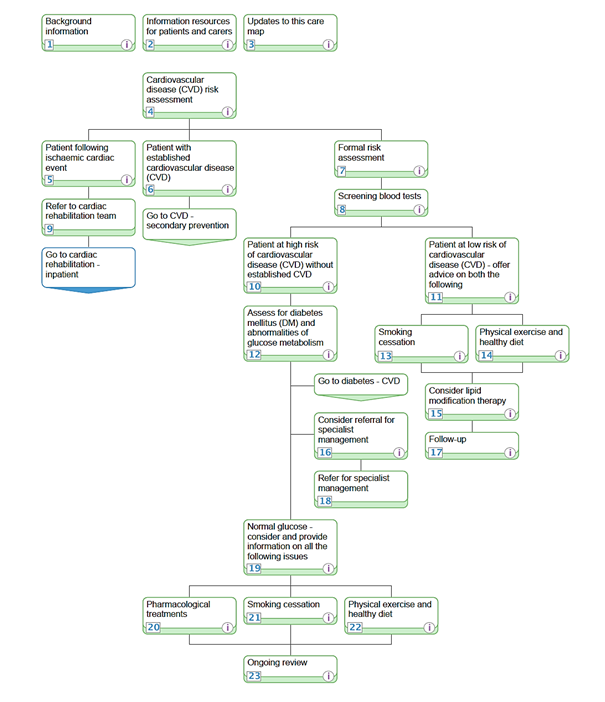

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk and prevention

CVD is a major public health problem as it known to be the leading cause of death in England[xvi],[xvii]. CVD predominantly affects people aged 50 and over; therefore making age the main determinant of CVD risk. The other main determinants of CVD risk are smoking, raised BP and raised cholesterol levels; the risk of CVD increases even more when these factors are combined. These factors account of 80% of all premature CHD[xviii].

QRISK®2 is a CVD risk score which is designed to identify people at high risk of developing CVD who need to be recalled and assessed in more detail to reduce their risk of developing CVD. The QRISK®2 score estimates the risk of a person developing CVD over the next 10 years. 10 year risk of CVD means the risk of someone developing CVD over the next ten years. If someone has a 10 year QRISK®2 score of 20% then they have a ‘one in five’ chance of getting CVD over the next 10 years. Incorporating ethnicity, deprivation, and other clinical conditions into the QRISK2 algorithm for risk of CVD improves the accuracy of identification of those at high risk in a nationally representative population[xix]

NICE are currently in the process of reviewing and updating their guidelines for Cardiovascular risk assessment and modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of CVD. The draft for consultation indicates that the threshold for offering statin treatment will be reduced from 20% to people with a 10% risk of developing CVD over the next 10 years. Furthermore, the recommended first line choice of statin has changed from simvastatin to atorvastatin.[xx] Further planning will be required to implement the changes in NICE guidance (once finalised); implications on local resource will have to be considered at this time.

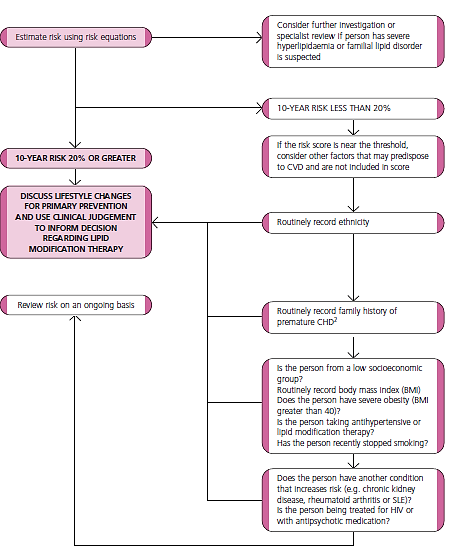

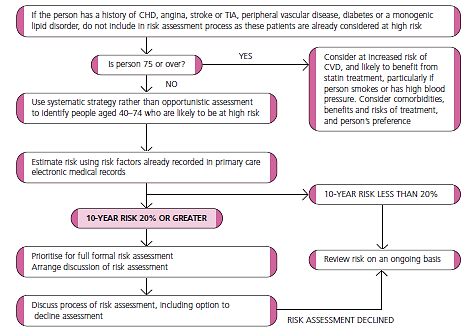

Below is an algorithm from NICE (figure 1) describing the process in performing a formal CVD risk assessment for patients (See NICE CVD risk prevention for full guidance on prevention and management of CVD risk).

Figure 2 Full formal CVD risk assessment

Source: NICE Lipid modification (2010)

Palpitations

The term palpitation can be used any time a patient complains of an abnormal awareness of their heart beat.

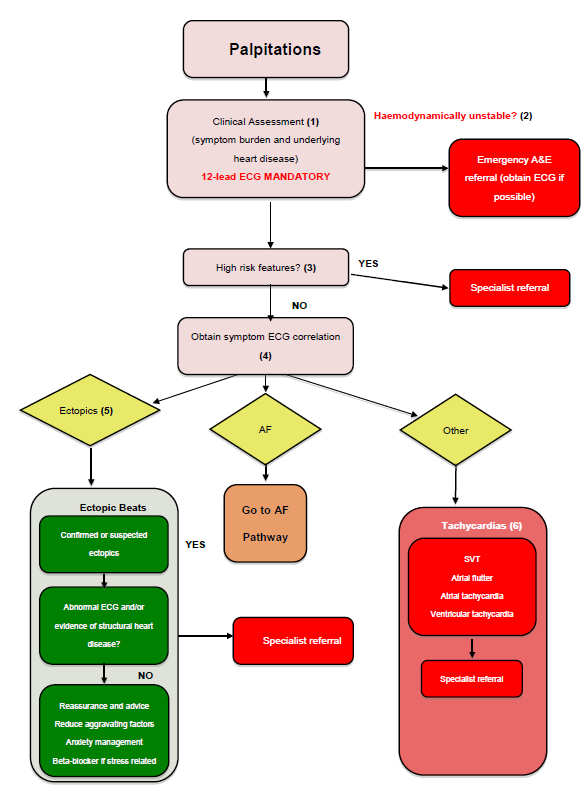

High risk factors to be aware of:

- History of pre-syncope/syncope

- Exertional cardiac symptoms

- Pre-existing heart disease ( HF, IHD, valvular and congenital heart disease)

From clinical guidance and literature referring to the diagnosis and management of palpitations, it would appear that the primary investigatory test that should be conducted to for a patient with suspected palpitations should be an ECG[xxi][xxii].

Arrhythmias

Palpitations and cardiac arrhythmias in patients are relatively common and the majority of these patients should be managed in primary care[xxiii]. A recent study in the UK demonstrated that a large number of patients with palpitations and arrhythmia symptoms did not require referral to cardiology services in secondary care and significant resources are dedicated to these low risk patients. By using a GP direct access BP holter and event monitoring service, the results showed that 96.2% of patients did not require referral to cardiology clinic and no reported adverse events[xxiv]. The monitoring of the heart’s rhythms is pivotal to the diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias. There are various types of arrhythmias and they can be detected by using different ways to monitor the heart’s rhythm under different conditions within primary care without having to undergo a formal review at a cardiology clinic:

- ECG/24 hr ECG – this can be used to confirm ectopic beats – early (premature) or extra heartbeats that can cause palpitations [xxv]

- Exercise Tolerance Test (ETT)

- Cardiac event recorder – this can be used if arrhythmia does not occur often

- Echo – this should be able to show if there are any problems with the heart muscles or heart valves.

- Electrophysiological (EP) testing – the patient must be referred to a cardiologist for this test to be conducted

The Resuscitation Council (UK) recommends strongly a policy of attempting defibrillation with the minimum of delay in victims of ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) cardiac arrest[xxvi] (both conditions are cardiac arrhythmias). It is recommended that automated external defibrillators (AEDs) should be available in all healthcare settings[xxvii] and all healthcare workers should also be trained, authorised and encouraged to perform defibrillation[xxviii] when necessary.

Figure 3 Primary care pathway for initial presentation of suspected palpitations

Source: Greater Manchester and Cheshire Cardiac and Stroke Network Primary Care Pathways

Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD)

SCD occurs in approximately 50,000–70,000 people annually in the UK; this is also representative of the largest proportion of the deaths attributable to CHD. Approximately 85–90% of SCD is due to the first recognised arrhythmic event; the remaining 10–15% is due to recurrent events[xxix].

Risk factors associated with SCD to be aware of, but not limited to[xxx]:

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Hypertension

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- Hyperlipidemia

- Dietary factors

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Physical inactivity

- Smoking

Rick factor interventions should be given to those who are at risk of CHD, including encouragement of moderate physical activity and other health promotion models[xxxi].

Heart murmurs

A heart murmur is an unexpected sound which a doctor may hear when listening to the heart with a stethoscope[xxxii]. Sometimes the murmur is caused by an underlying heart valve abnormality, but often there is no cause at all (innocent murmur).

For suspected murmurs, the GP should do the following[xxxiii]:

- Take a history and perform clinical examination ( use stethoscope to check the grade of the murmur- see table x below)

- If examination is normal, perform or refer for ECG

- If there are indications of heart disease, then refer to specialist cardiologist

- Patients with normal examinations and ECG can be referred to Direct Access Echo

- If the Echo comes back as abnormal, then refer patient to specialist.

Table 3 Intensity grades of heart murmurs

|

Grade |

Description |

|

1 |

Faint murmur that can only be heard after a few seconds have elapsed. |

|

2 |

Faint murmur that is heard immediately. |

|

3 |

Moderate murmur intensity. |

|

4 |

Loud murmur. |

|

5 |

Very loud murmur that occasionally can be heard when the stethoscope is placed only partially on the chest. |

|

6 |

Very loud murmur that can be heard when the stethoscope is off the chest entirely. |

Source: Lessard, E et al. Patient with a heart murmur. JADA, Vol.136 (2005)

Commissioning pathways

Commissioning is a vital part of the NHS healthcare system as it is there to ensure the right amount of clinical care is purchased and available for a particular population.

Below is a list of the various publications that can be used to assist services in commissioning the most appropriate, and clinically safe service for the diagnosis of patients with heart disease, or managing them effectively within the community:

- British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) (2011) Commissioning of Cardiac Services – A Resource Pack from the British Cardiovascular Society

- South West Joint Improvement Partnership (2010) A Toolkit to Support the Commissioning of Targeted Preventative Services

- Department of Health (2006) Adult congenital heart disease commissioning guide

Local Picture

Prevalence of cardiology conditions in Richmond

In Richmond, almost 32,000 of the GP registered population have a heart condition (including congestive heart failure (HF), hypertension, IHD, and AF; a rate equivalent 1,597 people with a heart condition per 100,000 in the Richmond population[xxxiv]. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is more prevalent in lower socio-economic groups and in certain ethnic minorities than the rest of the population[xxxv]. The National Service Framework (NSF) highlights that inequalities in the manifestation, detection, treatment and management of heart disease have arisen because information, services and resources are not adequately reaching those whose situations, position in society and lifestyle choices puts them at greater risk of CHD.

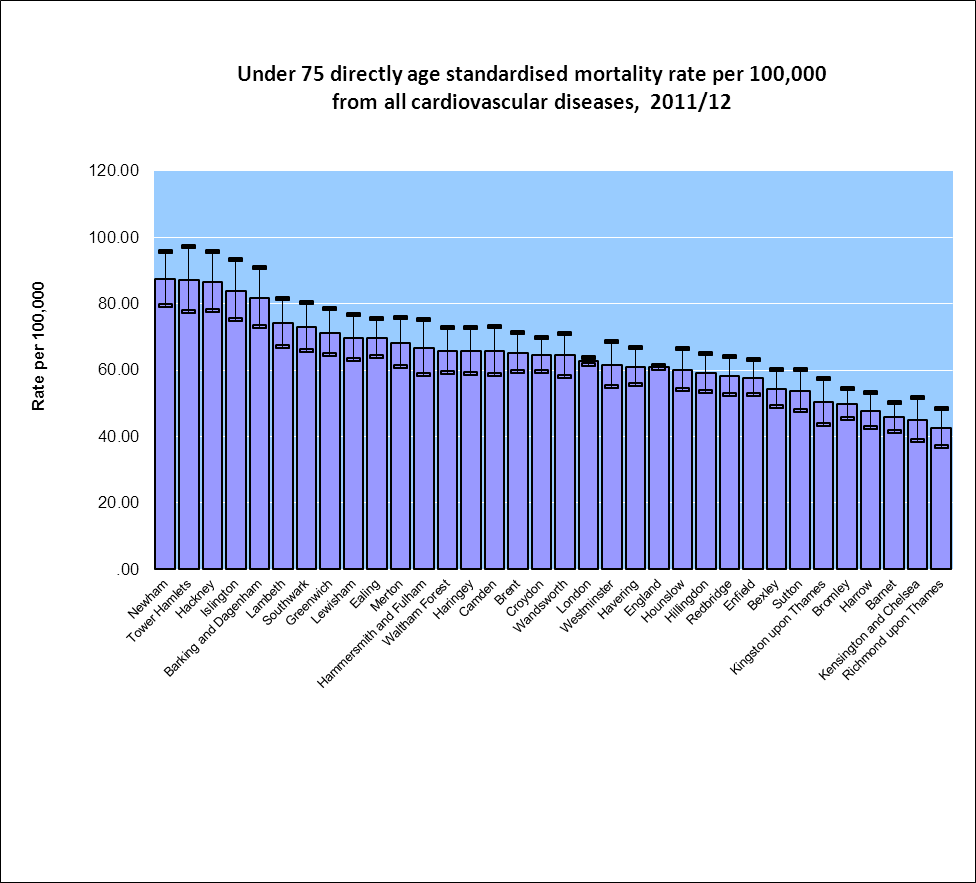

Out of all the boroughs in London, Richmond has the lowest SMR for people under 75 years with all types of CVDs (see figure 3). Observed improvement in the low levels of CVDs in comparison to other boroughs could be due to the weight-loss programmes within the borough, BP monitoring being conducted by GPs and CVD risk monitoring at primary care.

Figure 4 Under 75 directly age standardised mortality rate per 100,000 for all cardiovascular diseases by London Borough, 2011/12

Source: LBRuT Public Health Intelligence (2013)

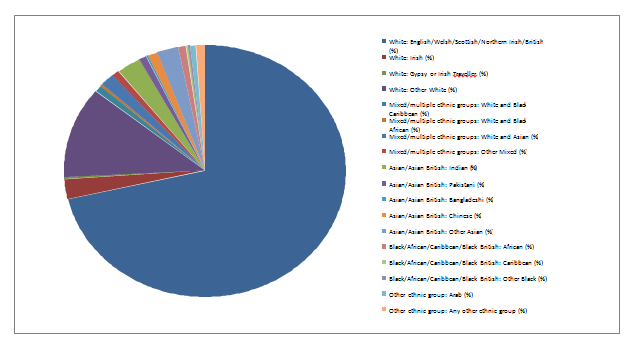

In Richmond, a large majority of the population (approximately 85%) of the population are White British with approximately 15% of the population from Ethnic minority backgrounds (see figure 4). Evidence has already highlighted the increased heart disease risk associated with these ethnic groups.

Figure 5 The Richmond borough percentage population by ethnicity

Source: LBRuT Public Health Intelligence (2013)

It is important to recognise the diversity within the LBRuT population, and the necessity to make adequate and accessible service provision for the minority groups to ensure they are aware of the services available to help prevent heart disease and/or manage an already identified heart disease. A small case study in the UK recognised there could be some benefit in identifying and managing heart disease in black and other minority community groups through having culturally adapted group sessions to raise awareness, offer medication reviews if necessary as well as BP monitoring.

Ageing population

Around 24,000 (12.6%) of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames (LBRuT) population are aged 65 years and over, which is higher than the proportion across London (11.5%) but lower than the England average of 16.3%[xxxvi]. Richmond also has over 4000 people aged 85 and over, which is a higher proportion than London (2.08% of the borough population compared to 1.66% London-wide)[xxxvii]. The life expectancy for the Richmond population aged 65 years and over is significantly higher than London and England (23 years for women, 21 years for men)[xxxviii]. These values clearly indicate that LBRuT is more likely to have a higher proportion of older people that will require multiple health and social care needs that will impact the way local services are provided.

Approximately 6% of the 65 years + population and 2% of the 85years + population are from Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds[xxxix]. As the number of older people in the borough is estimated to continue to increase, it is expected that the proportion of the BAME population within this age group will also increase. It is important to recognise the difference in need that exists for the ageing BAME population, as they are more vulnerable and more likely not to be utilising the borough services or face challenges when accessing cardiology services.

The more deprived wards in the borough are expected to have the largest increases in older people, which are expected between the ages of 65 to 74 years.[xl]

Co-morbidities

The key risk factors for cardiology conditions include smoking, physically inactive lifestyles, poor diet, excess salt, obesity, alcohol and diabetes. Other non-communicable diseases such as cancer, COPD, depression and dementia are also diseases closely linked with heart disease.

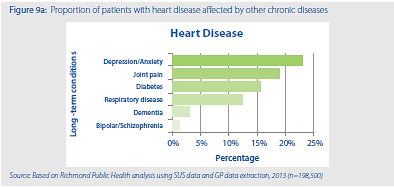

Figure 5 (below) shows the percentage of people with a long-term condition associated with heart disease in Richmond. Over 20% of people with heart disease in Richmond also have depression or anxiety. Over 15% of people with a heart condition in Richmond have at least three other long-term conditions, and 10% of patients have four other long-term conditions with depression and anxiety being most prevalent. This is an indication that a considerable proportion of cardiology patients in Richmond will require more than just clinical cardiology services to help them adequately manage their conditions; prompting a more integrated care approach to ensure the patient has access to all the necessary service, improving the patient experience.

Figure 6 Percentage of the Richmond population with heart disease and one or more other long-term condition.

Source: London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Public Health Annual Report (2013)

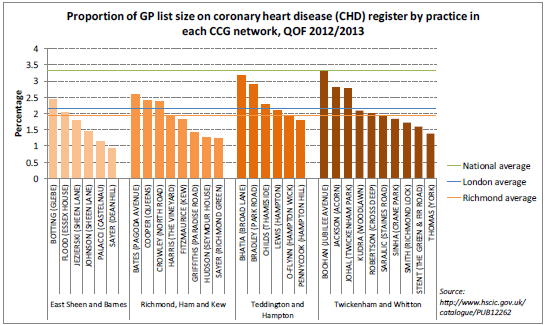

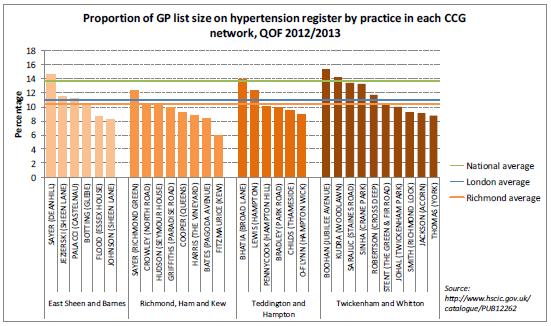

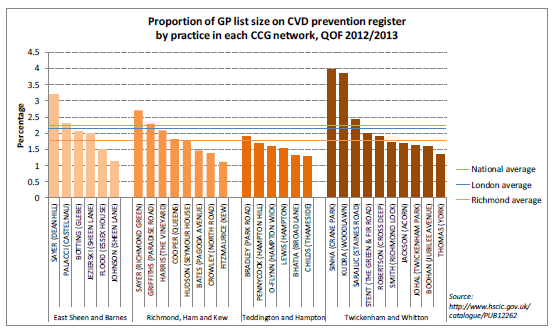

Figures 6, 7, and 8 (below) show an uneven distribution of heart disease within the borough. The graphs show that the highest proportion of GP registered patients on the CHD, hypertension and CVD register are situated in Twickenham and Whitton, comprising of some of the most deprived areas within the borough, demonstrating that heart disease is more prevalent in the deprived areas. It also has the highest population in the borough in comparison with the other LBRuT clinical networks within the borough. It is therefore necessary to review the cardiology services that residents in this area access the most to assess if the current services are appropriate and adequate to prevent and manage heart diseases effectively.

Figure 7 Proportion of GP list size on the coronary heart disease (CHD) register by practice (by locality)

Source: Richmond CCG Clinical Network Data Pack (2013)

Figure 8 Proportion of GP list size on the hypertension register by practice (by locality)

Source: Richmond CCG Clinical Network Data Pack (2013)

Figure 9 Proportion of GP list size on the cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk prevention register by practice (by locality)

Source: Richmond CCG Clinical Network Data Pack (2013)

The closest cardiology services to the Twickenham and Whitton residents are the community cardiology service run by Imperial College Hospitals Trust (ICHT) at Teddington Memorial Hospital (TMH) and West Middlesex University Hospital (WMUH). This review will be looking at all the cardiology services the key providers offer to Richmond residents. This review should be able to discover if there is a mismatch in the population’s cardiology healthcare needs and the current resources they access.

Diagnostic pathway for suspected/known cardiology conditions

Case for change

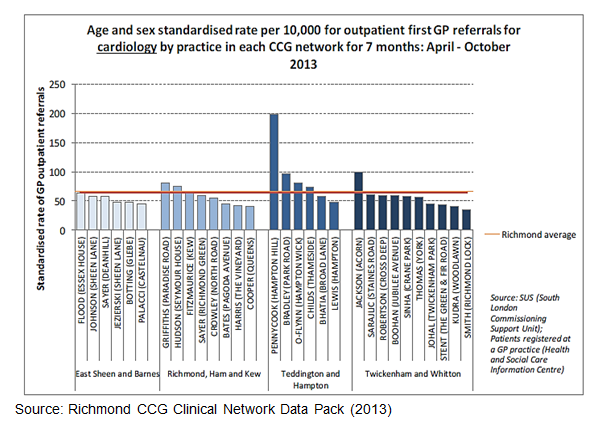

Variation exists in the way patients within Richmond are investigated and diagnosed with a cardiology condition between GP surgeries. Furthermore, intra practice variation exists, as there are differences within a surgery on how each GP will manage a patient.

The decision by a GP to refer to cardiology can be multi-factorial. Many pathways require a referral to access an investigation or intervention which may only be provided in secondary care. Access to B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and an Echocardiogram (Echo) can influence the provider a GP will refer to. GPs may know the likely diagnosis of the patient but will need to conduct investigations to confirm this; a referral to the cardiology department could be the only route to certain investigations such as an Echo or 24hr ECG (a number of GP surgeries in Richmond do not have 24hr ECG monitors)[xli]. GPs may be influence by a number of factors to refer patients to a particular service, and this is not exclusively clinical terms. Factors that influence GP referrals highlighted by healthcare professionals and the GP survey include:

- Access to diagnostics

- Patient choice

- Proximity of provider to patients’ residence

- Relationship between clinical professionals

- Confidence in provider

- GP competence and confidence

- Lack of knowledge of services other local providers can offer

- Fear of long waiting lists for patients

In Richmond, it is currently unclear as to what diagnostic tests GPs have access to within their surgeries locally and where patients are referred to for any tests that cannot be conducted at the GP surgery. It is also unclear what the referral criteria are for GPs referring patients on for diagnostics, additional tests, rapid access clinics or direct access clinics. Furthermore, it is unclear what the patient pathways are or how many different pathways exist once a patient is identified with a suspected or newly diagnosed cardiology condition.

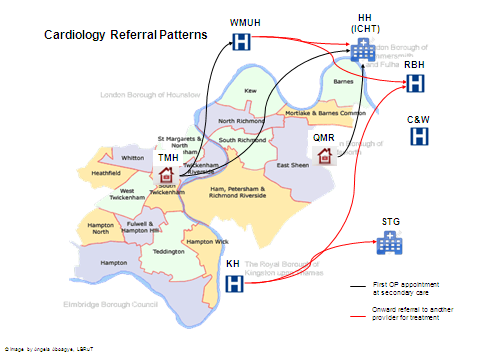

Since Richmond does not have its own hospital within its borough, a large majority of GPs do not have a choice but to refer patients to outpatient services in hospitals outside the borough for further investigation and treatment. The closest hospitals to the borough are Kingston Hospital (KHT), Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton (QMR), St George’s Hospital (SGH) and West Middlesex University Hospital (WMUH), and in some cases ICHT (Hammersmith Hospital). Therefore patients from Richmond have access to variable diagnostics, clinical services and are referred under variable criteria. Another point to consider is that these hospitals also sit in different cardiac and stroke networks and may have differing protocols for different diagnoses.

Richmond also has community cardiology service based at Teddington Memorial Hospital (TMH). This service has been commissioned by Richmond CCG and is delivered by cardiologists from ICHT. This service was designed to be of benefit to Richmond patients by providing them access to a high quality standard of clinical cardiology services at a reduced tariff. However, not all GPs within the borough are unaware of this service, or are aware and do not refer their patients to this service, resulting in the service not being fully patronised by the residents it was designed for, and not reaching its financial benefit in terms of first outpatients appointment at a reduced cost rather than full tariff rate at hospital. Furthermore, the current community service is not comprehensive, as it does not have access to all the diagnostics necessary for cardiology, 5 days a week. If a number of services are not available or accessible 5 days a week, this could be a strong reason why a number of GPs do not refer to this service, resulting in lower than expected referral numbers.

Reason for reviewing cardiology:

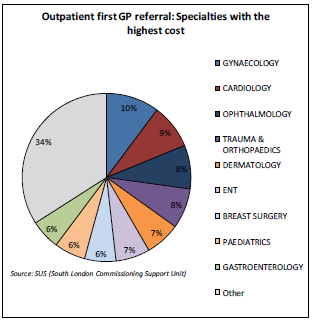

- Cardiology had the second highest speciality outpatient appointment (OPA) spend in Richmond in 2012-13

- Unclear if is heart disease is being managed appropriately by the GPs/community

- CVD is one of the biggest causes of mortality in the UK and 1/3 (32%) of deaths in LBRuT are due to CVD.

- There is a 5 year gap in CVD mortality between the least and the most deprived wards in LBRuT.

- National publications such as commissioning guides from NICE on Cardiac Rehabilitation show that commissioning an evidence-based cardiology rehab service in the community has the potential to improve the quality of care of the patients and reduce in hospital admissions resulting in massive savings. Therefore , Cardiology has been included as a potential QIPP scheme for 2014/15

- The June 2013 Spending Round announced the creation of a £3.8 billion Integration Transformation Fund – now referred to as the Better Care Fund – described as ‘a single pooled budget for health and social care services to work more closely together in local areas, based on a plan agreed between the NHS and local authorities The Better Care Fund (BCF) offers a real opportunity to address immediate pressures on services and lay foundations for a much more integrated system of health and care delivered at scale and pace. The BCF is not new or additional money and commissioners have to make important decisions about how the grant is used. Cardiology service review offers an opportunity to explore potential areas for improvement and investment to save public spending in the future and improve quality of life, better care within the community and outside hospital.

Reviewing the cardiology outpatient activity and diagnostic tests will provide a better insight as to where GPs are referring to, what diagnostics are available at each site, and what each provider charges for various appointments, and identify any potential savings that can be made via changing patient flow to services or renegotiating provider services.

Case finding and risk stratification

Case finding

If a patient presents to the GP, is assessed and it is determined that the individuals QRISK is higher than 20%, and has hypertension or/and diabetes, then the individual is at risk of having coronary artery disease (CAD). For this category of patients, they should be monitored annually in primary care and asked clear questions about any chest pains or related symptoms.

Every practice should have a systematically developed and maintained practice-based register of people with clinical evidence of CHD, occlusive vascular disease and people with a CHD risk of >20% over ten years in place and actively used to provide structured care to those at high risk of CHD[xlii]

NICE recommends that people aged 40–74 years who may be at high risk of CVD should be identified in primary care by estimating their CVD risk from existing medical record data. These people should be prioritised in descending order of risk and offered a formal risk assessment if their estimated10-year CVD risk is 20% or more[xliii].

NHS Health Checks

In LBRuT, the national CVD risk assessment and management programme is part of the NHS Health Checks programme which was initiated in the community in 2009. Currently, it is being delivered to all LBRuT residents between 40 to 74 years of age who do not have any known CVD conditions. Other exclusions are also applicable. The programme is being delivered by 29 general practices, 7 pharmacies and a community outreach provider. The programme has been commissioned by the LBRuT which is a mandated service. LBRuT has adopted a targeted approach to tackle CVD related inequalities. These include targeting the most deprived areas of the borough and prioritising people with high risk CVD, severe mental illness, people with learning difficulties and carers. Research has shown that, these vulnerable groups are more prone to CVD as compared to the general population.

The programme has been a success story in LBRuT, as it has helped to identify more than 500 people with CVD and referred more than 500 people to various life style services. Since 2009, nearly half of the eligible population has been invited and approximately one-third have received a health check. Those with a high and medium risk are being proactively managed in the general practice. LBRuT’s success story has been acknowledged widely and has been shared nationally at various conferences and events.

Figure 10 Identifying people for full formal CVD risk assessment

Source: NICE Lipid modification (2010)

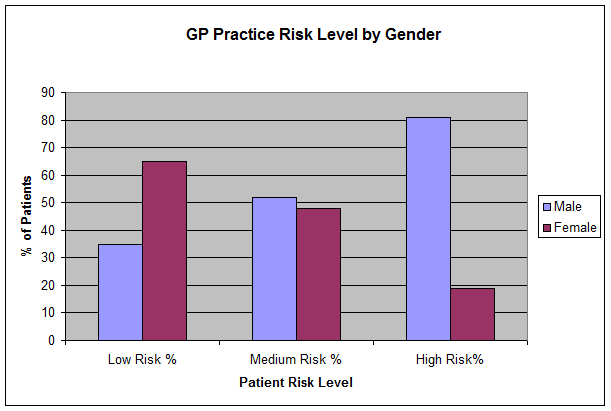

Figure 10 below gives a breakdown of the gender makeup of low, medium and high risk patients attending a health check between April and December 2013. Of the 3298 health checks completed between April and December 2013 59% of patients were female and 41% were male. This demonstrates that more females than males are accessing the service. In total there were 187 high risk patients identified within this time period; 151 of them were male, making up 81% of high risk patients. However, 65% of the low risk patients were female,

Figure 11 Risk level found in health checks by gender percentage between April and December 2013

Source: Richmond NHS Health Checks Service Review 2013 (Draft)

The health checks data for Richmond demonstrate that male patients are more likely to be at a higher risk of getting the specific non-communicable diseases including CVD and hypertension than women.

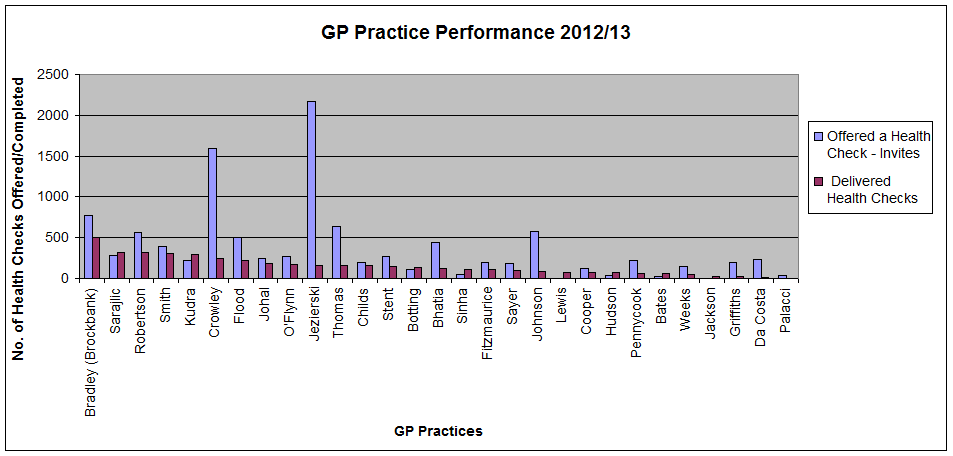

Figure 12 Number of NHS health checks offered and completed by GP practice, 2012/13

Source: Richmond NHS Health Checks Service Review 2013 (Draft)

N.B.: this graph has not been standardised by GP list size

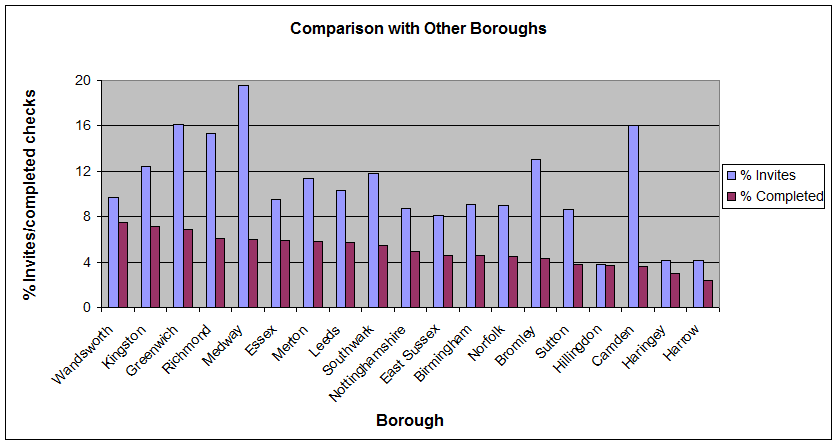

Figure12 below demonstrates that out of the 19 boroughs analysed for the NHS Health Checks, Richmond completed the fourth highest percentage of health checks relative to its eligible population in the first two quarters of 2013/14 (6.1%). Richmond was also fourth best for the percentage of health check invites.

Figure 13 Comparison of performance by percentage of invites (invites divided by eligible cohort) and completed health checks (checks divided by eligible cohort) in the first two quarters of 2013/14 (April – October 13)

Source: Draft NHS Health Checks Service Review

For angina, diagnosis is usually based on the history of the patient[xliv]. The Rose angina questionnaire has been found useful to identify a number of angina patients; however this does vary in its sensitivity when compared with clinical diagnosis[xlv].

Patients with mental health conditions

A UK qualitative study demonstrated various barriers that may exist when trying to screen people with severe mental illnesses (SMI) for heart disease risk factors and/or interventions for primary prevention. These barriers include[xlvi]:

- Lack of appropriate resources in existing services

- Anticipation of low uptake rates by patients with SMI

- Perceived difficulty in making lifestyle changes amongst people with SMI

- Patients dislike having blood tests

- Lack of funding for CHD screening services or it not being seen as a priority by Trust management

It is necessary to be aware of these potential barriers and establish close links with the mental health teams on how to identify, treat and manage these patients. It has already been identified earlier in the review that over 20% of patient with heart disease suffer from depression/anxiety; meaning over 1/5 of people with heart disease in Richmond have a mental health condition, which equally needs to be addressed and managed in conjunction with heart disease.

Risk stratification

Risk stratification using clinical scores should be conducted to identify those patients with an ACS who are most likely to benefit from early therapeutic intervention[xlvii].

Local risk stratification conducted by the Public Health Intelligence team (PHIT) at Richmond can also be used to identify patients that have a number of morbidities and that may be at risk of having a cardiology condition, and should therefore be monitored by the GP.

Whilst the review team are aware of the contribution smoking makes to the risk and prevalence of CHD, the scope of this review does not include smoking cessation. More information on smoking cessation services and support in Richmon can be found on the Live Well Richmond website: https://www.live-well.org.uk/richmond/

Local Services

Cardiac and Stroke Network

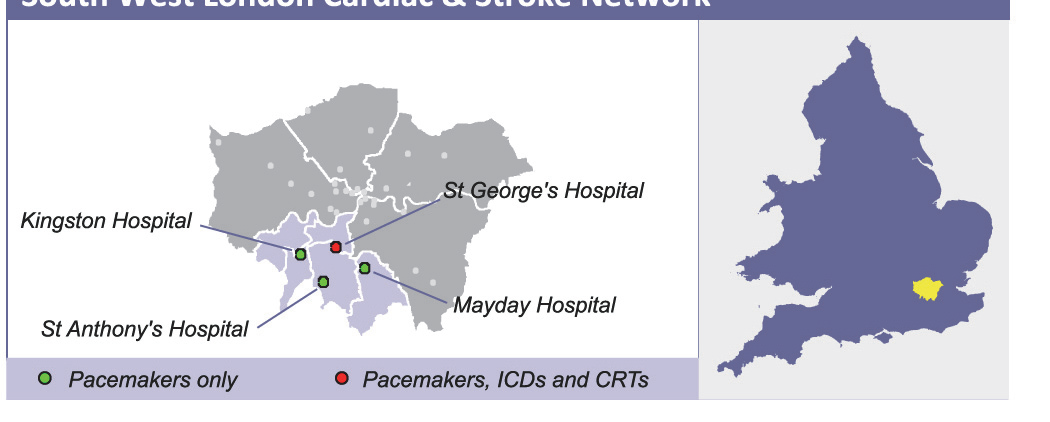

In 2010, the Commissioning Support for London’s model of care for cardiovascular services[xlviii] recommended that cardiac and stroke networks should be implemented across England to consolidate treatment for these services, giving patients access to the best, specialised care to provide the greatest chance of survival. In London, five Cardiac and Stroke Networks were formed and Richmond sits within the catchment area for the South London Stroke and Cardiac Network (SLCSN). Each network has nominated stroke and cardiac tertiary centres whereby certain specialist cardiac and cardiothoracic procedures are only performed at these centres. St George’s Hospital is the tertiary stroke and cardiac centre primarily serving the south west London population. From 1 April 2013 the SLCSN work programme transitioned to the London Strategic Clinical Networks (SCN) hosted by NHS England.

Due to the geographic location of the network, there is more than one London Cardiac centre that is relatively accessible to Richmond residents. The other stroke and cardiac centres in London that a proportion of Richmond patients are regularly referred to by GPs or other providers are:

- Imperial College Healthcare Trust (ICHT) (Hammersmith, Charring Cross and St Mary’s Hospital)

- Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust (RBH)

Specialised cardiology and cardiac service activity is concentrated in relatively few specialist centres to ensure a sufficient volume of activity is undertaken to develop and maintain expertise

The list below encompasses seven specialised service areas that specialist centres manage:

- Heart, lung and heart & lung transplantation services (including implantable ventricular assist devices) – There are seven nationally designated centres for adults and two for children in England.

- cardiac electrophysiology services

- inherited heart disorder services

- congenital heart disease services

- cardiac surgery and invasive cardiology

- pulmonary hypertension services

- cardiovascular magnetic resonance services

Governance

Governance is an important area within any type of service being provided to the community, especially healthcare. For Richmond patients, wide variation exists between the different cardiology services that are accessed by Richmond patients. This variation exists for a number of reasons:

- LBRuT does not have an Acute hospital within the borough

- Different London CCGs commissioning a variation of services

- GPs within the borough are not using a universal assessment and referral criteria for cardiology

The variation in services and governance has resulted in a number of LBRuT residents experiencing inequitable cardiology services, which can have an impact on their recovery time, and experience. It is the duty of LBRuT and the Richmond Clinical Commissioning Group (Richmond CCG) to ensure that LBRuT patients have access to the best service possible and are not discriminated against in the process of accessing these services. Similarly, Richmond CCG may not be commissioning appropriate services fit for the purpose and according to the local needs of the population.

General Practitioners (GPs) in Richmond

Once a patient is seen in clinic, the GP will decide if they require further testing. Dependent on the resources the GP has, they may be able to perform some tests, also known as ‘working up’ the patient before referring them on to the community services or outpatient service to have further tests and/or a cardiology appointment.

The GPs in Richmond do not have a universally agreed criterion for the referral of cardiology patients for further investigation. This inevitably means that cardiology/suspected cardiology patients that have GPs within Richmond have an inequitable service from the beginning of the pathway, as referral criteria differs from surgery to surgery, from GP to GP and amongst different cardiology outpatient services.

GP Cardiology Services and Provision in Richmond Questionnaire (LPIS) 2013

In November 2013, a cardiology service questionnaire was sent out to all the GP surgeries in the LBRuT. There was a 100% response rate, making the data collated reliable and demonstrable of what is happening in the community with regards to cardiology. However, a point to note is that the questionnaire was not completed by each GP, rather a GP on behalf of each surgery.

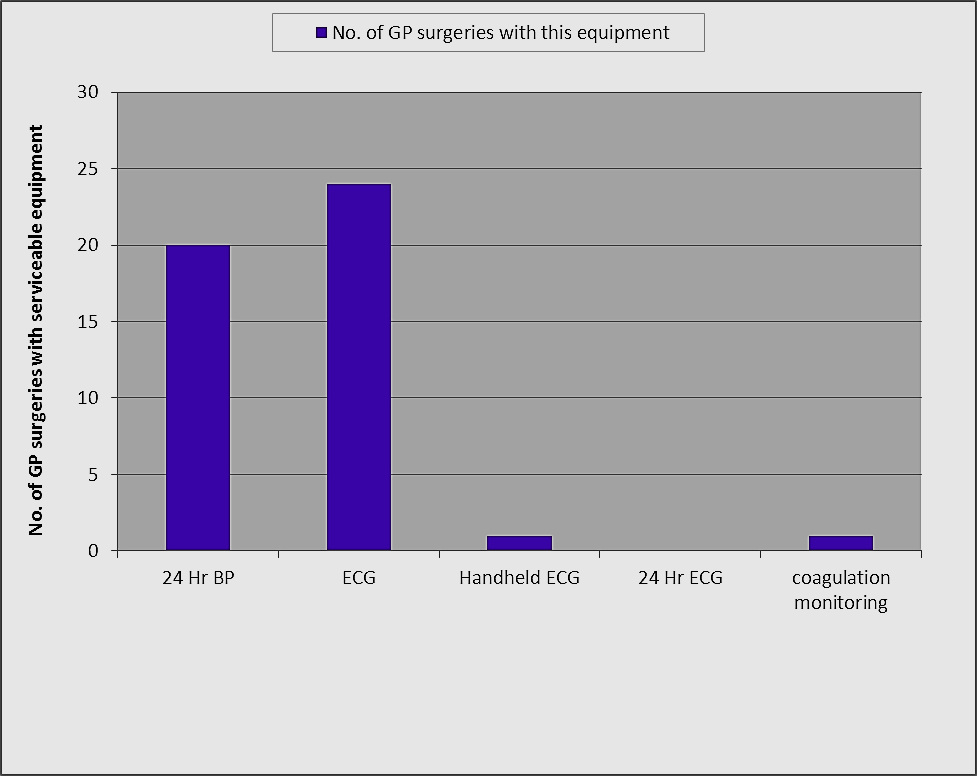

Serviceable equipment at practices in Richmond

Figure 13 (below) shows that most GP surgeries within Richmond possess an ECG and 24hr BP monitor. Therefore GPs should be able to perform these tests on patients instead of referring them to other services that will charge for these diagnostics. Only 2 practices in Richmond reported that they had an anticoagulation monitor. Anticoagulation monitoring necessary to ensure the anticoagulant blood levels are within the International Normalised Ratio (INR). NICE recommends anticoagulation monitoring for AF patients before and after cardioversion[xlix] (AF diagnosis, treatment and management in primary care to be covered in part 2 of the cardiology review).

Figure 14 GP surgeries in Richmond with serviceable equipment

Source: Cardiology Services and Provision in Richmond Questionnaire (LPIS) 2013.

GP referral preference

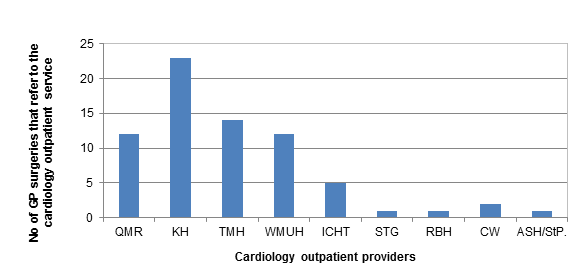

Figure 14 (below) shows that the 22 out of 31 GP surgeries in LBRuT refer their cardiology patients to Kingston Hospital for further investigation or treatment. However, this does not imply that 22 GPs exclusively refer all their cardiology patients to Kingston cardiology services. 2/3 of LBRuT GP surgeries send cardiology referrals to KHT. The results also show that the community cardiology service is used by almost 50% of the GPs, shortly followed by QMR and WMUH. It was expected that the specialist (also known as tertiary) cardiac centres would not have a high volume of initial referrals, as they should not usually be the first point of call; however, a 5 GP practices stated that they refer some of their patients to ICHT for their first cardiology appointment. GPs response to the survey in regards to where they send initial referrals are not directly reflected in the overall activity and spend for the initial referral to key outpatient cardiology services.

Some GPs mentioned they were not aware of the Richmond community cardiology service at TMH, and would consider referring to this service in the future. Other GPs expressed their discontentment with their patients having to go to Charring Cross/Hammersmith/St Mary’s hospital for further investigations/secondary care once being seen at QMR or TMH because of the distance patients would have to travel. This indicates that the cardiology consultants from ICHT delivering community cardiology services at these sites refer patients that need further treatment to their base hospitals (CHX/HH/SMH), which is not always the closest specialist cardiac centre to Richmond residents. However, it may be the closest option for those living in the Barnes and East sheen area. Secondly, some of the tests or treatments carried out at ICHT could be carried out at other key providers that may be closer to the residents.

Figure 15 Preferred place of referral for outpatient appointments

Source: Cardiology Services and Provision in Richmond Questionnaire (LPIS) 2013.

Types of clinics GPs refer to and ‘work-up’ tests

- Some GPs would not do any work-up at all – they would refer patient straight to clinic for this.

- Doing work up depended on the specific cardiology condition the GP suspected

- Dependent on GP access to services and what equipment they had in the surgery to carry out any tests.

- RACPC commonly referred to if patient expressed chest pain

- Unsure if patients referred to rapid access clinic are being referred appropriately.

How GPs manage post-cardiac event patients

- “Follow guidelines. Optimise blood pressure and lipids (but often lipid targets in hospital exceed outcomes achievable with community pharmacy advice

GPs opinion on what secondary care services could do to assist in the better management of cardiology patients

- “Improved access to diagnostics”

- “Clear, accurate and more informative discharge letters, specifying diagnosis and medication (s) prescribed”

- “Better education of patients’ before discharge”

- “GPs and secondary care clinicians to work together to redesign cardiology referral pathways”

- “Improve pathway for AF when diagnosed in A&E”

Overview about the service by GPs

- Need more communication between consultant and GP

- Would be useful to have easier access to ambulatory monitoring, which at present requires a referral to TMH cardiology clinic and likely classed as a new referral.

- QMR – onward investigation at SMH (ICHT) is too far for patients to travel

- Patients who go to QMR to be offered choice of hospital for onward referral according to the original agreement, all are referred on to SHM (ICHT)

Service improvement suggestions

- Look at risk calculators vs coronary calcium scores for those who are neither very high risk primary prevention (e.g. diabetes) no very low risk.

- Suggestion of GP Led Cardiology Clinic in the area (GPwSI)

- Providing an urgent email/telephone service would be a great improvement and beneficial to both GPs and patients.

- Community heart failure (HF) Nurse Specialist

- Would be useful to have easier access to ambulatory monitoring, which at present requires a referral to TMH cardiology clinic and likely classed as a new referral.

- New anticoagulants for cardiology or haematology

- Possibly arranging teaching sessions for GPs

The survey results have shown that Richmond GPs could do more in primary care to improve the level of care for cardiology, in terms of assessments and diagnostics carried out at primary care presentation. They also need to be better informed about the Richmond community services available, the SLCSN cardiac network provider and have access to the necessary equipment to be able to provide initial work up such as ECGs that are necessary for initial diagnosis. Over 57% of GPs have ECG and 24hr BP monitors, and should therefore be able to conduct the necessary initial work up necessary for suspected and known cardiology patients instead of these tests being done by providers and the CCG being charged for this.

The GP survey also highlighted the issue of patient choice (or lack thereof) at the point of onward referral from QMR and TMH to ICHT. All patients seen at these hospitals requiring further investigations or treatments are routinely referred to ICHT and are not offered the choice of going to other providers unless they state they would like to.

Community Cardiology services

Community services are designed to support primary care management of cardiac and suspected cardiac conditions through the provision of direct access diagnostic services and a community based one stop model of outpatient services. In this setting a patient can have all the necessary diagnostic testing done, then have clinic review. Dependent on the review, the clinician will formulate a management plan and send to the referring GP, or refer the patient to a cardiology outpatient department for further investigation and review with a cardiologist.

Community cardiology services should be able to carry out all the main diagnostics that GPs may not be able to in order to better determine the appropriateness of referring patients to secondary care. The service should act as a “gate-keeper” accessing outpatient cardiology services, however, this does not appear to be the case with the current ICHT commissioned community cardiology service based at Teddington Memorial Hospital.

Teddington Memorial Hospital (TMH)

For Richmond, TMH is the community hospital based within the borough. Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton (QMR) is also a community hospital in the neighbouring borough with cardiology clinics being provided by ICHT cardiologists; however, it appears that Richmond patients are being treated at this service under the acute tariff and not community tariff as is being done at TMH.

In 2010, NHS Richmond and Twickenham (now Richmond CCG) signed a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with Imperial College Hospital Trust (ICHT) to provide community-based cardiology services outside of an acute setting for only NHS Richmond patients at Teddington Memorial Hospital (TMH). This service was designed to give easy access to Richmond Borough patients living in the Twickenham, Teddington and Hampton locality to local cardiology services. The aim of the community service is to reduce the amount of inappropriate referrals to cardiology outpatient departments in secondary care. It is also designed to give patients the benefit of local access to cardiology services- however; it does not provide a comprehensive cardiology service 5 days a week. This service does not have a rapid access chest pain clinic (RACPC) service, pain nurses, variation of diagnostics needed, and neither all-day diagnostics. The service also faces IT challenges which has an impact on sending patient diagnostics to other trusts.

The provision of blood tests and chest x-rays has not been included in the service delivery scope. Therefore, these tests should be completed by GP’s prior to patient’s attending appointment, or they have the option of referring patients to diagnostic facilities managed by Hounslow and Richmond Community Healthcare (HRCH).

TMH also hosts speciality cardiology clinics run by ICHT consultants:

- Arrhythmia clinics

- Hypertension

- Ischaemic Heart Disease (IHD)/ valve disorders

- Chest pain service (this is not a RACPC)

Table 4 Suspected conditions and the tests that would be performed at TMH

|

Conditions |

Diagnostic tests required |

|

Palpitation |

24hr ECG monitoring Echocardiogram (if indicated) ECG Bloods requested by GP prior to referral : thyroid function test, U&E’s, FBC |

|

Shortness of breath/Heart Failure

|

Echocardiogram ECG Bloods requested by GP prior to referral : U&E’s/ FBC/ Creatinin Chest X-ray requested by GP prior to referral |

|

Chest Pain

|

Exercise tolerance test (if indicated) Echocardiogram (if indicated) ECG |

|

Hypertension |

Echocardiogram (if indicated) ECG 24hr Blood Pressure Monitoring (if indicated) |

|

Murmurs |

Echocardiogram ECG |

Source: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Service Level Agreement document for the Richmond Community Cardiology service (2010)

The community cardiology service provides one-stop direct access clinics for NHS Richmond patients referred by their GP. This service has access to the following diagnostics:

- 24hr ECG tests

- Echocardiogram

- Exercise tolerance test ( ETT)

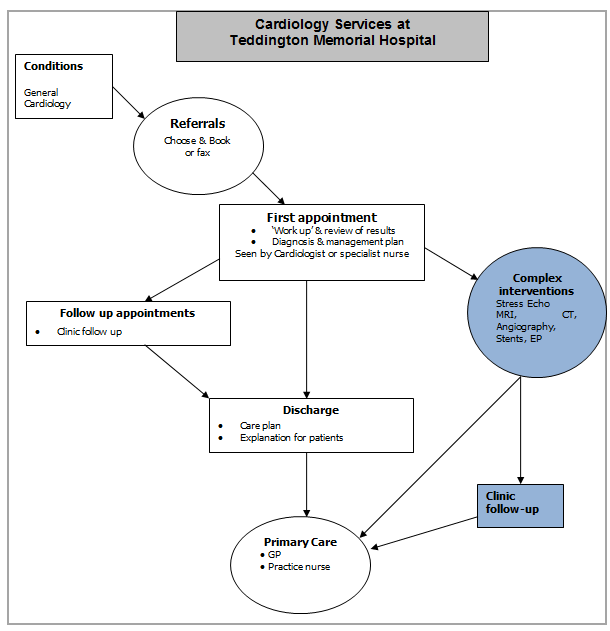

The algorithm below describes what a typical patient journey from GP presentation to referral to the TMH community service and possibly beyond should look like in accordance with the SLA.

Figure 16 Step-by-step diagram flow of the patient pathway from GP presentation to TMH cardiology community service.

Source: NHS Richmond & Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, 2012.

N.B.: Symbols shaded in green signify activity in secondary care. The complex interventions mentioned on the diagram are conducted at ICHT, not at the community service. Also, the current SLA for the community service does not include a follow-up service; so this would also be done at ICHT before discharge back to the GP.

From the GP cardiology questionnaire it is apparent that not all GPs are aware of this community service commissioned especially for the Richmond community. Aside from that, a number of GPs are under the impression that QMR has been commissioned to provide a cardiology community service for LBRuT residents, and refer patients their as an alternative community service for Richmond; however this is not the case. Richmond patients referred to QMR are not being charged a community rate in the same way as the TMH service.

It is very important to know the number of patients seen at TMH that have onward referrals to providers far away from the borough, as the community service was established to provide a more convenient and accessible service for local residents. Therefore, sending them further outwards for secondary care whist there may be providers nearer by that can provide the same level of service does not appear to be the best choice for the residents. If the patient requires an onward referral to secondary care, there is not an agreed nominated provider that the community service should refer to as per the SLA; however, it appears that all onward referrals are sent to the same cardiologist that sees them at TMH at ICHT.

Challenges facing the community cardiology service in TMH:

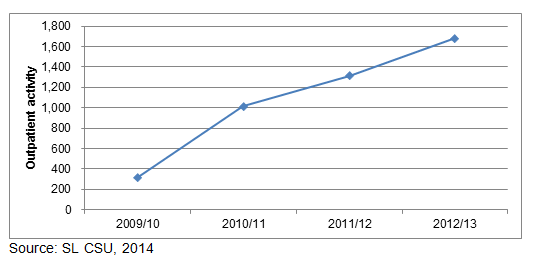

- Low capacity attendance – not as many GPs are referring to this service as initially anticipated. The SLA stated that the maximum projected demand for this service was 6650, with the provider capacity able to service 4000 people. In 2012/13, the reported total activity for TMH was 1,232 appointments (of which 634 were direct access Echo appointments)[l]. This is less than half of the original projected activity (as per the SLA) for Richmond cardiology community service.

- 80% of referrals for direct access to diagnostics and appointments are booked by fax and not choose and book (C&B); however, TMH clinics are available via C&B. This means that a high number of referrals do not pass through RCAS for review of appropriateness.

- Use of the word community and the effect it has of patient perception.

- Lack of adequate space currently hired to have a fully functioning cardiology service

- IT- the IT system in TMH is not connected to ICHT, or any of the other key providers IT systems, causing some initial delay in receiving the test results. This is likely to result in tests being repeated and incur duplicate costs to the CCG for the same test.

- Service prices are due to increase in the financial year 2015/16 (the current contract has been rolled over for financial year 2014/15 with no financial changes to current agreed costs). With ICHT due to increase the charges for the community services, it is time to evaluate the current service to see if it is meeting the patient’s clinical needs and delivering to expectations.

- Lack of all the diagnostics and expertise needed to have a comprehensive community cardiology service to adequately ‘triage’ patients and refer them onwards to a provider or back to the GP as appropriate.

Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton (QMR):

QMR has GP direct access clinics for cardiology patients as well as new patient assessment clinics and some rapid diagnostic clinics. QMH is a part of St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust and is within the Wandsworth borough; however, a proportion of Richmond GPs refer Richmond patients to this service. Even though QMR cardiology outpatient services are accessible for Richmond patients, it sits in a different borough with a different provider. Furthermore there is a lack of clarity about what QMR about the community service provision for Richmond patients i.e. if their services are being charged at a lower community tariff or at the normal acute provider tariff. Therefore it is necessary to understand what type of service is hosted by QMR, the activity of Richmond patients attending this service and the financial implications. If a high proportion of Richmond cardiology residents are having outpatient appointments at QMR, it would be reasonable to explore the possibility of setting up a community service agreement similar to the service delivered at TMH.

Prior to this review it was thought that the QMR cardiology service is part of Richmond’s community service. However, through this review it has been discovered that QMR has not been commissioned by Richmond CCG to deliver community cardiology services to Richmond patients. This means that any services procured at QMR will be charged at a tariff that may well be higher than the present community tariff at TMH.

There is only one cardiology service operating at QMR, which is provided by ICHT. This service has not been negotiated by Wandsworth CCG in the same manner in which Richmond CCG has done with ICHT for the community service at TMH.

Aside from the general cardiology outpatient’s clinic, QMR hosts other cardiology clinics:

- Specialised arrhythmia clinics (run by a ICHT electrophysiologist consultant and CNS)

- RACPC (see appendix 10 for pathway)

- Rapid access diagnostic murmur clinic

- Rapid access diagnostic heart failure clinic

- Rapid access diagnostic Hypertension clinic

N.B. The rapid access cardiology clinics provide a range of same day diagnostic tests which appeals to a number of Richmond GPs.

QMR service has access to the following diagnostics for cardiology:

- ECHO

- Pacemakers

- ECGs

- ECG holter monitors

- BP monitors

- Patient Activated Recorders

- Full Lung Function Service including reversibility studies

Patients initially seen at QMR cardiology outpatients department will be reviewed by an ICHT consultant. If they feel further diagnostic evaluation is needed that is not available at QMR, or treatment is required, then these patients are routinely referred directly to St Mary’s Hospital (ICHT). QMR’s invasive cardiology service is provided in full by ICHT. At present, patients are not referred to SGH or any other hospital unless they express their opinion to go elsewhere.

Richmond Clinical Assessment Service (RCAS):

Richmond has commissioned a peer review system which provides triage of eligible referrals from GPs to acute care. Experienced local GPs review routine GP referrals and help to decide the best option for assessment and treatment, providing peer support. Patients referred to rapid access clinics or urgent out-patient appointments do not have their referrals reviewed by RCAS.

The service was developed with the aim of providing NHS Richmond patients with equitable access to appropriate services. NHS Richmond commissioned this service based on the local needs assessment and analysis that identified high referral rates from primary to acute care. RCAS service uses the telephony and booking service more commonly known as ‘Choose and Book’ (C&B) to gain access, review and manage referrals from Richmond GPs to acute care, The assessors use the South West London Effective Commissioning Initiative

(SWL ECI) policy and local guidelines as a triage tool and if further evidence is required this is discussed with LBRuT Public Health team.

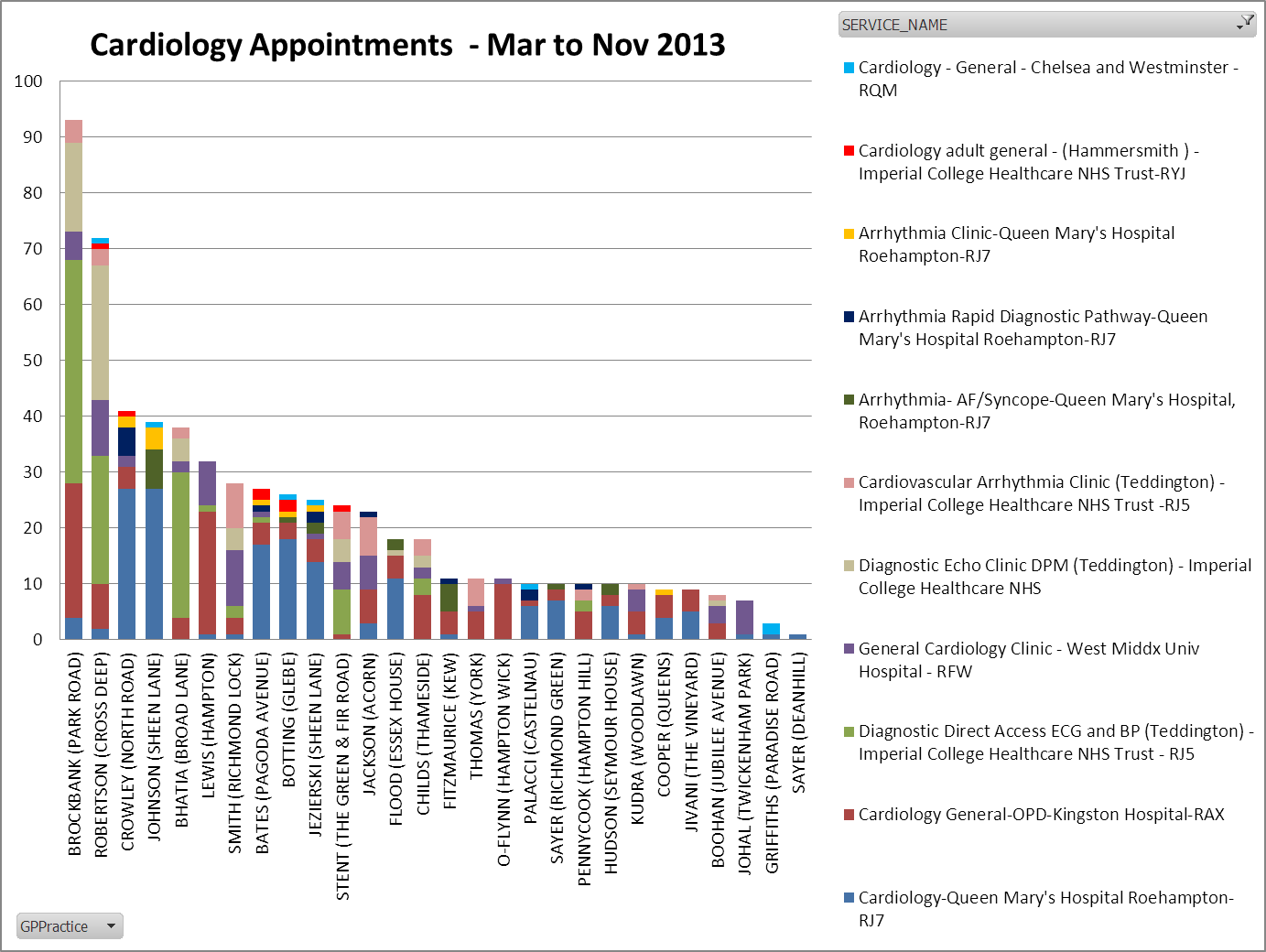

Figure 17 Number of cardiology initial GP referrals to key providers by GP practice over a 9 month period from March to November 2013

Source: RCAS

It is important to note that approximately 50% of GPs use the RCAS service for routine referrals and approximately 50% of all cardiology referrals are made through RCAS. There are a notable proportion of GP referrals being made via fax and consultant letters. This demonstrates the various pathways that exist to access cardiology services in an outpatient setting,

This graph has highlighted the following:

- There are various outpatient services relating to cardiology that GPs can refer to.

- The GPs refer most to KH, TMH and QMR. This confirms the findings in the GP survey, with 2/3 of practices referring to Kingston. However, this graph is able to show the proportion of referrals sent to different providers, giving us further indication of GP preference.

- Park road surgery has the highest number of referrals during this period at 94; this is over 20 more referrals than any other surgery within the same timeframe. The majority of referrals made at this surgery are primarily to TMH cardiology and direct access Echo service, then KHT. This surgery sits within the Teddington and Hampton clinical network area and is in close proximity to TMH.

- 11 GP practices in Richmond use QMR as their first preference for cardiology outpatient services.

- 11 GP practices refer their patients to the TMH arrhythmia clinic, whilst 6 different GPs refer their patients to the QMR arrhythmia clinic, albeit smaller referral numbers.

- 12 GP practices refer cardiology patients to WMUH, albeit at varying preference. Only two GP practices use WMUH as their first preference for cardiology referrals.

- 2 GP practices refer directly to Chelsea & Westminster Hospital (C&W) and 5 GP surgeries refer directly to ICHT (Hammersmith Hospital). These results corroborates the GP survey response, showing few GPs referring directly to ICHT, therefore, they should not record a high number of first attendances.

- This graph shows that none of the GPs in Richmond refers their cardiology patients to SGH via RCAS in the first instance.

Rapid access chest pain clinics (RACPC) and direct access clinics

In 2000, the National Service Framework for coronary heart disease identified rapid access chest pain clinics (RACPC) as the appropriate model of choice for the assessment of patients presenting with suspected angina, with chest pain as the primary characteristic.

Patients that present to the GP with chest pain should be referred to the RACPC for specialist assessment. The RACPC clinics are designed to provide a one-stop service involving clinical assessment and investigations to confirm or exclude angina coronary artery disease (CAD). The clinics also set the patients onwards to evidence-based treatment (revascularisation).

There is a lack of knowledge around what is happening across the borough in regards to RACPCs. Services need to be mapped to understand if things are working well, or if there is a need to commission something different.

Direct access clinics are usually walk-in or appointment services for diagnostic tests. These clinics do not include an assessment or consultation with a clinician.

Current Service Providers

Richmond GPs currently refer patients to Rapid Access Chest Pain Clinics (RACPC) at the following providers:

- Kingston Hospital NHST Trust (KHT)

- West Middlesex University Hospital NHST Trust (WMUH)

- St. George’s Hospital (SHG)

- Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICHT) (Charing Cross, ST Mary’s and Hammersmith Hospital)

- Queen Mary Hospital, Roehampton (QMR)

- Royal Brompton and Harefield Healthcare NHST Trust (RBH)

Each RACPC has its own referral criteria usually contained within the general cardiology referral proforma, so the reasons/conditions for referral may differ – even if only slightly. An important point to highlight is that the Richmond community cardiology service at TMH does not have a RACPC. The result of this means that fewer patients are referred to this service, reducing the capacity seen and patients are referred to their closest RACPC service which is usually WMUH.

Kingston Hospital NHS Trust (KHT) rapid access clinic:

Kingston hospital runs a cardiology rapid access clinic 4 times a week.

West Middlesex University Hospital (WMUH) rapid access clinics:

The Rapid Access Chest Pain Clinic (RACPC) at WMUH conducts specialist assessment of patients with suspected new onset Angina within two weeks from referral. This service also identifies cardiac risk factors and enables people to assess their values and contemplate behaviour change.

St Georges Hospital rapid access clinic:

The Rapid Access Chest Pain Clinic (RACPC) at SGH is accessible 5 days a week and performs same day diagnostics.

Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton (QMR) rapid access clinics:

QMR hosts rapid access clinics for chest pain, rapid arrhythmia, heart murmur and hear failure.

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICHT) rapid access clinics:

RACPCs are available at Hammersmith, Charring Cross and St Mary’s Hospital five days a week.

Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Trust (RBH) rapid access clinic:

RBH has RACPC’s two days a week; patients are seen by appointment only.

Hospital outpatient and diagnostic services

Kingston Hospital NHS Trust (KHT):

GPs are able to refer to KHT’s one-stop cardiology clinic via the ‘choose & book’ system, as well as faxing referrals to the rapid access and walk in diagnostic services.

Some specialist cardiology clinics at KHT are run some jointly with St George’s Hospital NHS Trust (SGH) clinicians, including interventional cardiology consultants and a consultant cardiac electrophysiologist. KHT offers a range of diagnostic tests, and has its own catheter laboratory to conduct invasive tests.

The following diagnostic tests are available:

- ECG and ambulatory/24 hour ECG

- BP

- Exercise Tolerance Test (ETT)

- ECHO

- Trans Oesophageal ECHO

- 7 day event recorders

- Diagnostic angiography

- Myocardial perfusion imaging

KHT has a dedicated cardiology in-patient ward with a ‘step down’ unit to manage rehabilitation of coronary patients. Cardiology procedures performed at KHT include permanent pacemaker insertion and cardioversion day case treatment.

The criteria for referring patients initially seen at KHT cardiology outpatients department to SGH are as follows:

- Patients who require percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and structural heart interventions,

- Complex pacing and cardiac electrophysiology (EP) procedures etc.

- Advanced imaging such as stress Echos or cardiac MRIs.

- Patients who require a specialist OP opinion such as Inherited Cardiac Conditions (ICC), Structural Heart Disease or pulmonary hypertension, and in some cases refractory hypertension.

- Patients who require cardiothoracic surgery.

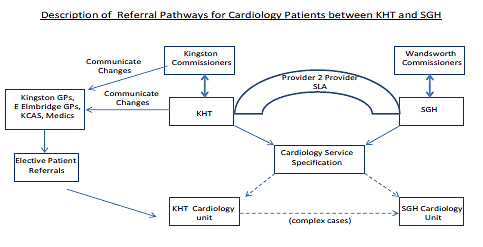

There is a joint Service Level Agreement (SLA) between KHT and SGH to provide rapid access to specialist tertiary services locally for patients having their outpatient appointments of secondary care at KHT. This results in a number of inter-hospital transfers from KHT to SGH for specialist cardiac services in accordance with the pan-London cardiac services. Figure 17 (below) depicts the cardiology patient flow that exists between KHT and SGH.

Figure 18 Flow diagram to show the patient cardiology referral pathway flow between KHT and SGH

Source: Cardiology at Kingston Hospital (2012)

The criteria for referring admitted cardiology patients from KHT to SGH are as follows:

- Patients who require emergency coronary intervention (high risk NSTEACS), pacing or EP procedures.

- Patients who require urgent, rather than emergency procedures.

- Patients who require urgent cardiology/CT surgical MDT management (e.g. complex endocarditis)

- Patients who require inpatient cardiac surgery

There are no specific criteria for the referral of cardiology patients from KHT to RBH as the designated cardiac referral centre for KHT is SGH. However, when it is apparent that a timely transfer of an inpatient (IP) for further care is not possible, KHT liaise with other interventional centres for continued management, with RBH being close by and accessible. In other cases when the patient has had a long history of management by clinicians at the RBH or multiple previous procedures (i.e. well-established on a pathway there); it is deemed reasonable by KHT clinicians to re-refer the patient back there to ensure continuity of care.

Kingston CCG is also running a pilot Patient-Centred Angina self-Management programme (PCAM), which is due for review in April 2014. The intervention is a community based outpatient education programme with an initial 1:1 session followed by four group sessions and a follow up group session at 3 months and 12 months. There is some evidence that these types of self-management programmes can reduce health care utilisation such as hospital admissions. Patients selected for this programme will be either those with refractory angina[1] or those contemplating scheduled palliative Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI)[2] with stents or balloons.

Richmond CCG decided to wait till the Kingston PCAM pilot’s evaluation and findings were made available. If appears that the Kingston CCG PCAM pilot is successful and shows an improvement in the patient’s quality of life (QoL) as well as demonstrating significant cost savings, then Richmond CCG will consider commissioning the service. However, it will be necessary to aligned with the existing services such as the Expert Patient Programme and cardiac rehabilitation programme with PCAM.

St George’s hospital NHS Trust (SGH):

The cardiac unit at SGH is a specialist tertiary referral centre for all types of adult cardiac and thoracic surgery and is the cardiac centre that primarily serves the south west London area.

SGH are currently in the process of expanding their cardiac department with the addition of 10 new catheter beds and a new treat and return unit in the first quarter of 2014. This should create more capacity for cardiology patients at SGH. Two pathway co-ordinators are also in the process of being appointed at SGH, with these roles being pivotal in the timely management of patient care and any necessary transfer of patients to and from SGH.

The following diagnostic tests are available at SGH:

- Direct access:

- ambulatory BP monitoring

- electrocardiography

- ambulatory and cardiomemo ECG monitoring

- ECG holter monitoring

- Cardiac MRI

- exercise tolerance testing (ETT)

- cardiac CT

SGH has an established adult congenital heart disease service and can perform a number of congenital interventions in the form of atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale closure procedures.

West Middlesex University Hospital NHST Trust (WMUH):

WMUH provides an open access walk-in service for GP referred patients requiring routine ECGs with physiologists to provide initial ECG interpretation and referral to the relevant medical team. Where possible, WMUH provide same day diagnostic tests for all the cardiology clinics offering a one stop (direct access) service.

Below is a list of the cardiology diagnostics available at WMUH:

- 24 hour, 48 hour and extended direct access ECG holter monitoring

- Event recording

- 24hr BP monitoring

- Direct access exercise tolerance testing (ETT)

- Direct access simple/complex/agitated saline/contrast Echo’s

- Treadmill and dobutamine stress Echo

- Cardiac CT and calcium scoring

WMUH has a dedicated Cardiac Care Unit (CCU) for inpatients, however it does not have a catheter lab; therefore patients requiring this service are referred to other providers:

- ICHT for out-patient catheter services

- ICHT and RBH for in-patient catheter services

- RBH for complex heart failure catheter services

For patients that require invasive cardiac tests and cardiac/cardiothoracic interventions and other specialist cardiology services in secondary care, the majority would be referred to ICHT (HH); this is the cardiac centre in the North West London Stroke and Cardiac Network and is the closest cardiac centre to the hospital. WMUH also has a close relationship with RBHT and also refers a majority of its cardiothoracic patients to their service for further investigation and treatment. WMUH works with both ICHT and RBH on the non-elective pathway to offer patients a choice of provider and to minimise delays in the process of care.

The criteria for referring admitted cardiology patients from WMUH to ICHT are patients who require interventional treatment including:

- coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

- Complex electrophysiology (EP)

Referral from WMUH to RBH would occur for complex heart failure (HF) patients needing a full assessment including for cardiac transplantation

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICH):

The cardiology services for this trust are spread across three hospital sites; Hammersmith Hospital (HH), St. Mary’s Hospital (SMH), and Charing Cross Hospital (CXH); each having their own outpatient appointments and diagnostic equipment. Patients are usually referred to these hospitals for further investigation and/or treatment by community – based cardiology services (TMH, QMR) or a district general hospital (WMUH). The trust also has a service whereby GPs and practice staff can contact their cardiology medical specialists directly with clinical queries and questions through the Trust’s new pilot GP advice service.

HH is one of the eight nominated heart attack centres in London, providing invasive tertiary cardiology and cardiothoracic services primarily for the North West London area. HH has specialist expertise in the emergency treatment of patients with acute coronary syndromes. The International Centre for Circulatory Health (ICCH) is based at SMH.

The pathway for Richmond patients that have their first cardiology outpatient appointment at WMUH and will require further investigation and/or treatment are referred to HH. Patients seen at QMR and TMH requiring further investigations and/or treatment are referred to SMH.

Private services

The LBRuT is one of the most affluent boroughs within London with over 50% of the population within the least deprived quintiles and less than 1% within the lowest deprivation quintile. With this type of population mix, it is noted amongst the local GPs that there are a proportion of patients that prefer to use the private care system for further investigations and treatment once they are told by their GP that they may have a suspected cardiology condition. However, it is not clear whether data relating to their condition once they are treated and discharged back to their GP is captured by the QOF programme.

Private diagnostic service

InHealth are a private diagnostic service provider, with direct GP referral, in addition to the Imperial community based service at TMH. The InHealth contract is managed by NHS England and had a 15% savings on tariffs; however this contract will terminate at the end at the end of March 2014. The imaging reports conducted by InHealth are sent back to the GP; however the GPs have expressed issues with the interpretation of the results and this seems to have adversely affected the number of referrals and led to underutilisation of the service by GPs.

The results from the LPIS Richmond GP survey (2013) as well as soft data demonstrate that none of the GP surgeries in Richmond actively refer their patients to InHealth for cardiology imaging diagnostic tests.

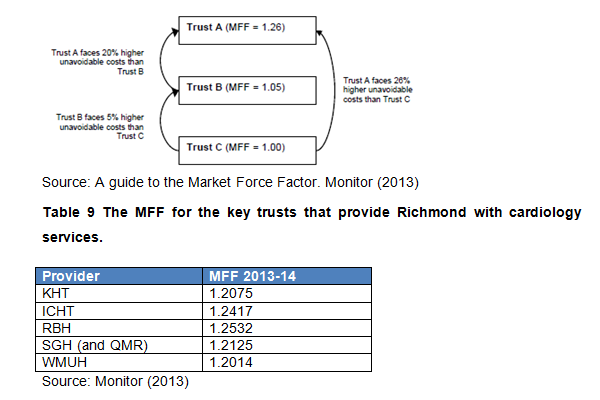

Activity and financial costs of current services