Source

This report is largely based on the content of a chapter from the 2013/14 Report of the Director of Public Health, London Borough of Richmond upon Thames published in January 2014.

However, based on an update of content and review of conclusions, this report was published in February 2015.

1 Introduction

1.1. Aim

This needs assessment report sets out the current and future challenges that multimorbidity presents to patients, their carers, friends and families, and the NHS and social care in Richmond.

It also highlights key messages to guide the development and commissioning of services that deal effectively with multimorbidity, by moving from the current single disease management approach, to a more integrated and comprehensive model of care better meeting the need of individuals experiencing multimorbidity.

1.2. Who is this for?

This needs assessment report is intended to inform the policies, strategies, development and commissioning plans, and practice in local organisations including Council teams, NHS organisations such as the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and Trusts, and other organisations, such as the voluntary sector and representatives of the public and patients.

2 Background

2.1. Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity is usually described as the co-existence of two or more long-term conditions in an individual.[1] For instance, this could include people diagnosed with heart disease and diabetes, or respiratory and heart disease, or anxiety/depression, and joint pain.

The coexistence of both physical chronic conditions and mental health problems such as anxiety and depression is particularly important since the prognosis for the physical condition and quality of life can deteriorate markedly.[2] In addition, the costs of providing care to this group of people are increased as a result of less effective self-care and other complicating factors related to poor mental health.[2]

Improving the way we support an individual with both physical and mental health problems would have a high impact in terms of patient experience and clinical outcomes, since both of these outcomes are substantially poorer relative to those for people with a single condition.[3] Integrated models of disease management have been found to deliver savings four times greater than the investment required,[4] and there are now models of liaison psychiatry in acute hospitals.[3]

Research also suggests that multimorbidity involving a mental health condition is more common in the poorest socioeconomic groups, who are also more likely to develop multimorbidity at a younger age and to have greater mental health problems, and consequently compounding difficulties in the successful management of their condition.

Local patterns of multimorbidity in Richmond upon Thames are provided in the following chapter.

2.2. Impact of multimorbidity

Multimorbidity has a range of implications for public health, and the health and social care system. In summary these include:

- The total multiplicative health and wellbeing impact on individuals, their carers, and populations overall.

- Increasing case complexity and intensity of health and social care needs faced by providers and carers.

- Need for patient-centred, holistic and integrated care delivery to improve the patient experience & outcome.

- Inefficiency of the current organisational model of health and social care services, and challenges of service re-organisation.

- Knowledge and training of clinicians (e.g. regarding contraindicated therapy options).

Currently, health services and health policy are largely organised around single diseases and do not often take multimorbidity into account, despite the evidence that many people have more than one long-term condition.[5] Increasing sub-specialisation and the decline of generalism in hospital settings can create a lack of co-ordination and oversight of patients’ multiple needs.[6] These factors impact on the health outcomes and wellbeing of patients and their carers, and costs to the health and social care systems.

3 Local Picture

3.1. Current & future population

Approximately 198,500 people are registered with a Richmond Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) general practice, and the majority, around 90%, also live in the borough.

The number of people living in the London borough of Richmond upon Thames is expected to grow by approximately 3,000 each year until 2018. The expected overall increase for this period in those aged 65 years and above is 2,800 (10%). Life expectancy at birth in Richmond is 82 years for men and 86 years for women.

As a result, the number of people living with long-term conditions[*] (i.e. conditions that cannot be cured but can be managed through medication and/or therapy over a period of years or decades), will increase.

3.2. Multimorbidity & age

As shown in Table 1, analysis of GP data and hospital data for the Richmond CCG registered population, shows that nearly one in three had one or more long-term condition and nearly one in ten had three or more. Strikingly, the number of people with three or more long-term conditions increases from 4% in people under the age of 65 to 44% in those over the age of 65.

Table 1. Number and percentage of people with multimorbidity, 2013.

|

People with one or more long-term conditions |

Number |

Percentage of the corresponding population |

|---|---|---|

|

Total |

63,000 |

32 |

|

Aged < 65 years |

41,000 |

24 |

|

Aged ≥ 65 years |

22,000 |

81 |

|

People with three or more long-term conditions |

|

|

|

Total |

18,600 |

9 |

|

Aged < 65 years |

6,600 |

4 |

|

Aged ≥ 65 years |

12,000 |

44 |

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, 2013

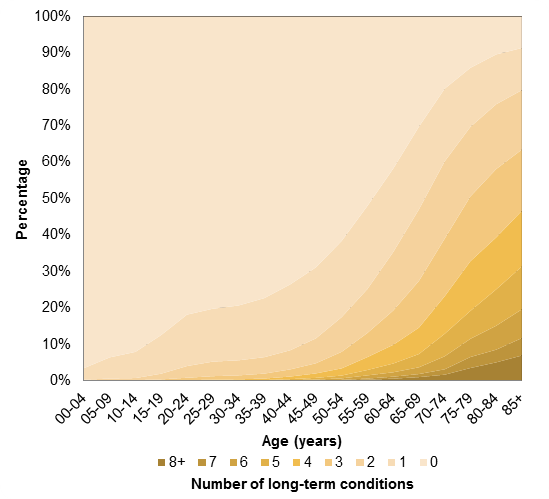

This well recognised association of multimorbidity with age is illustrated in Figure 1. However, a substantial proportion of those with three or more long term conditions are younger than 65 years, and as a result their particular needs and circumstances (e.g. employment and absenteeism) [7] should also be taken into account in the commissioning and delivery of health and social care services.

Figure 1. Number of long-term conditions by age, 2013.

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, 2013 (n=198,500)

3.3. Patterns of multimorbidity

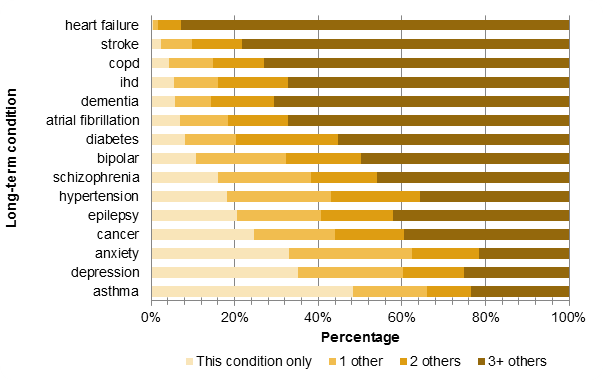

As shown in Figure 2, the percentage of people with at least one other long-term condition varies depending on the long-term condition. The highest is heart failure – 93% of those with heart failure have three or more long-term conditions compared with 23% of those with asthma. For most people living with any one of the long-term conditions listed, multimorbidity is the norm.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients who have other long-term conditions, 2013

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, 2013 (n=198,500)

Nearly 32,000 of Richmond CCG registered population have a heart condition (including congestive heart failure, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease (IHD), disorders of lipid metabolism, atrial fibrillation and stroke). Around 12,000 suffer from chronic respiratory disease, for example, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Joint pain caused by musculoskeletal problems, such as, rheumatoid arthritis, low back pain, and gout, affects some 13,000 patients, see Table 2.

Table 2 Number and rate per 10,000 population of some of the major long-term physical and mental health disease areas.

|

|

No. Of patients |

Rate per 10,000 |

|---|---|---|

|

Heart disease |

31,706 |

1,597 |

|

Respiratory disease |

11,758 |

592 |

|

Diabetes |

5,840 |

294 |

|

Joint pain |

12,880 |

649 |

|

Dementia |

1,191 |

60 |

|

Depression/Anxiety |

20,023 |

1,009 |

|

Bipolar/Schizophrenia |

861 |

43 |

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, April 2013 (n=198,500)

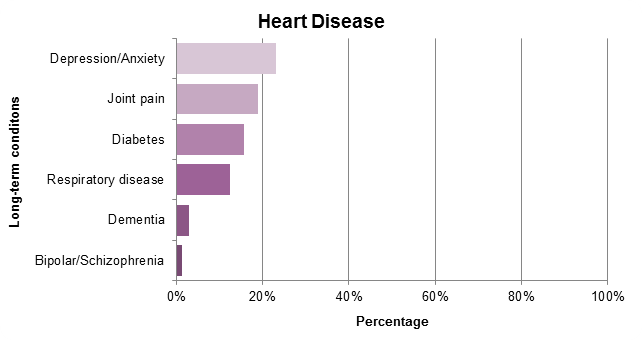

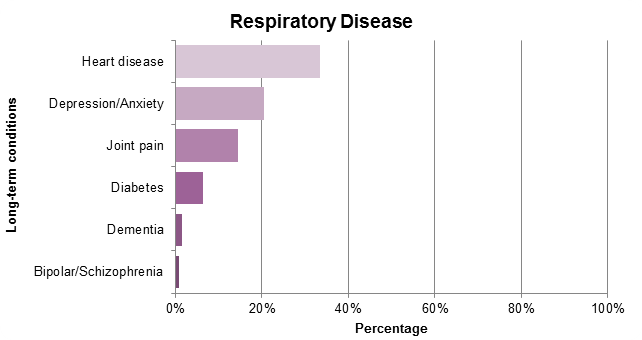

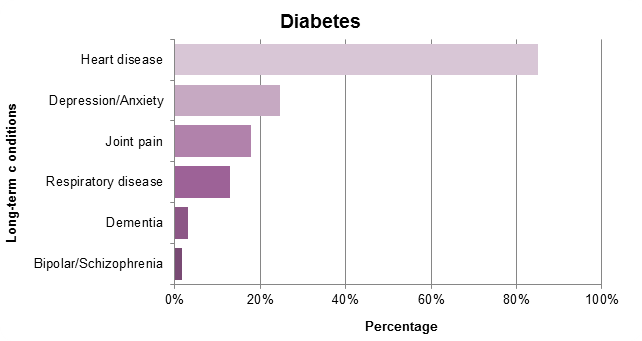

One in ten of the population in Richmond suffers from minor mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. As shown in Figure 3 below, 20-25% of patients with heart disease, respiratory disease, diabetes or joint pain, experience depression and/or anxiety. Also, 40% of dementia patients have depression/anxiety.

Figure 3. The proportion of people with heart disease, respiratory disease, diabetes, joint pain, and dementia, and affected by other long-term conditions.

3.4. Hospital service use

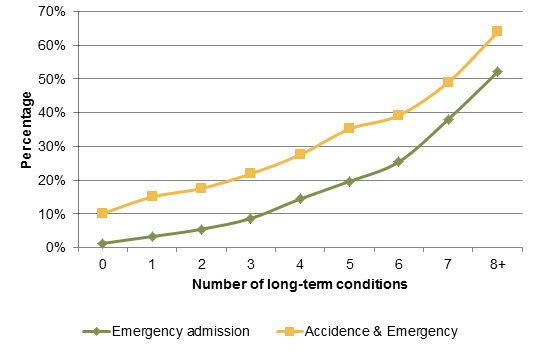

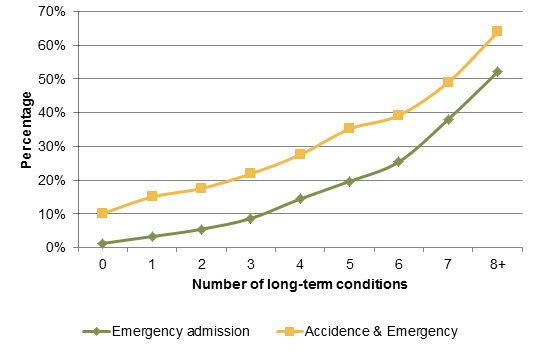

As shown in Figure 4, local analysis finds that the percentage of people attending Accident and Emergency (A&E) or an emergency hospital admission at least once a year, rises steeply with increasing numbers of long-term conditions.

Figure 4. Percentage of patients who attend A&E or had an emergency hospital admission, 2013

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health Analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, 2013 (n=198,500)

In 2012/13, 27,000 registered patients had at least one A&E attendance and 7,100 had at least one emergency hospital admission. However, it is the small proportion of individuals with 3 or more long term conditions (9%) that account for over a quarter (26%) of A&E attendances and more than half (54%) of all emergency admissions.

3.5. Medicines use

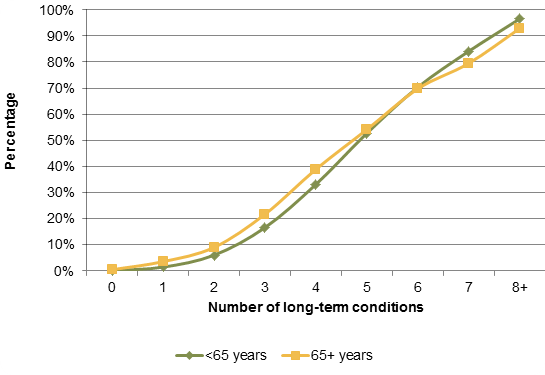

Similarly, as shown in Figure 5, local analysis also demonstrates that the percentage of patients with more than 10 unique prescriptions per year rises sharply with increasing multimorbidity.

Figure 5. Percentage of patients over 65 years and under 65 years who had more than 10 unique prescriptions per year, 2013

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health Analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, April 2013 (n=198,500)

Appropriate use of medicines is particularly important for those with multimorbidity since these patients will often be on multiple medications (‘polypharmacy’). Polypharmacy can be appropriate for patient care, but it is associated with greater risks of unwanted effects, and is often particularly problematic in people who are physically frail or have cognitive impairment. Polypharmacy is an extremely strong predictor of A&E attendance and hospital admission, partly due to adverse drug reactions.

3.6. Costs

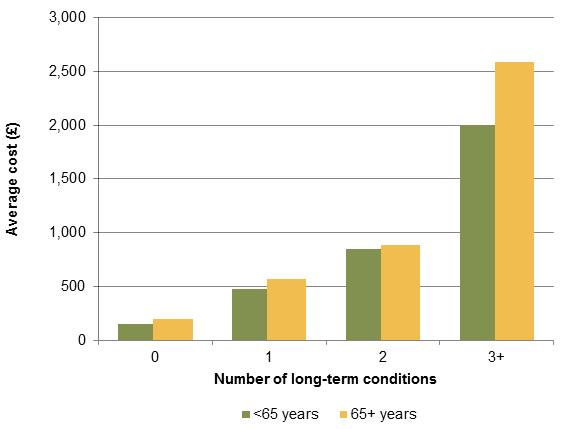

These additional health care burdens also impact on costs.

As shown in Table 6, the average annual community prescribing and acute hospital spend on a patient in one year increases with multimorbidity. For example, the average spend in one year for a patient age 65 or over with two long-term conditions is £900 compared with £2,600 for a patient with three or more long-term conditions.

Figure 6. Average acute hospital cost using Payment by Results tariff and community prescribing cost, 2013

Source: Based on Richmond Public Health Analysis using SUS data and GP data extraction, 2013 (n=198,500)

[*] Long term physical and mental health conditions included in this report: congestive heart failure, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, disorders of lipid metabolism, atrial fibrillation, stroke, cancer, diabetes, hypothyroidism, obesity, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic renal failure, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, Parkinson’s disease, seizure, multiple sclerosis, age-related macular degeneration, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, low back pain, gout, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy.

4 Local Services

This chapter outlines how local strategies, commissioning plans, and services can be developed to respond more effectively to the needs of people with multimorbidities in Richmond upon Thames.

The increasing challenges presented by multimorbidities and the local Richmond picture outlined in previous chapters, are recognised in a number of local initiatives. A selection of these are summarised below.

- Recognition of the needs for integration of the consideration of physical and mental health issues, and integration of health and social care service delivery, in a range of key local strategies, including the Richmond Health and Wellbeing Strategy[8] and Out of Hospital Strategy[9].

- Care pathway reviews (e.g. dementia, diabetes, neurology, COPD) including explicit consideration of multimorbidity, and exploration of increased service integration, holistic care, and multidisciplinary delivery.

- Adoption of predictive risk tools[†] in clinical practice to identify and proactively manage patients at most risk of needing unplanned and expensive care, through service developments such as the Richmond (virtual) Community Ward.

- Identification and targeting of upstream prevention and lifestyle change support needs through the Richmond LiveWell service to prevent complications and improve self-management in people with long-term conditions.

- Using the Better Care Fund to design and implementation of service innovations to tackle the challenges of multimorbidity, including:

- 7 day Richmond Response & Rehabilitation Team.

- Care Home Pilot.

- Community Independent Living Pilot.

- GP care co-ordination/case-management model.

- Self-management/assistive technology/tele-health.

- Personalised care, including direct payments & personal health budgets.

- Psychiatric liaison service.

[†] The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System www.acg.jhsph.org

5 Conclusion

Multimorbidity is an important current and future challenge for health and social care in Richmond. The key conclusions from this needs assessment report are summarised below.

- The ageing population in Richmond as elsewhere means more people with more than one long term condition will become the norm. Long term conditions can often interact with each other resulting in an increase in the complexity of care.

- It is especially important to recognise the common co-existence of physical and mental health conditions as outcomes for each are worsened when they occur together.

- There is a need for policy makers, commissioners and providers of services to move away from traditional single disease pathways, typical in current care models. Instead there needs to be a shift towards recognising multimorbidity as a condition in its own right.

- This will require a holistic approach where patients, carers and professionals work together with the aim of optimising wellbeing and quality of life rather than treating single diseases. Locally the work on integrating health and social care services is an attempt to put this approach into practice.

References

[1]Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O’Dowd T (2012). Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ:345;e 5205

[2] Naylor C et al. (2012). Long term conditions and health: the cost of comorbidities. King’s Fund. [Online] www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/long-term-conditions-andmental-health.

[3] Nuffield Trust (2012). Care for older people: projected expenditure to 2022 on social care and continuing health care for England’s older population.

[4] Howard C, Dupont S, Haselden B, Lynch J, Wills P (2010). The effectiveness of a group cognitive-behavioural breathlessness intervention on health status, mood and hospital admissions in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychology, Health and Medicine: 15(4): 371–85.

[5] Guthrie B et al. (2012). Adapting Clinical Guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ: e6341.

[6] Finlay I, Cayton H, Dixon A, Freeman G, Haslam D, Hollins S, Martin F, Taylor C, Brindle D (2011). Guiding Patients Through Complexity: Modern medical generalism. Report of an independent commission for the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Health Foundation. Health Foundation website. [Online] www.health.org.uk/publications/generalism-report.

[7] Turner BJ, Cuttler L. (2011). The complexity of measuring clinical complexity. Ann Intern Med: 155: 851-2.

[8] Health and Wellbeing Strategy (May 2014) https://www.richmond.gov.uk/health_and_wellbeing_strategy_april_13.pdf.

[9] Better Care Closer to Home Richmond Out of Hospital Care Strategy 2014 – 2017 (January 2014) https://www.richmondccg.nhs.uk/strategies%20policies%20and%20registers/Better_Care_Closer_to_Home_strategy.pdf.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Equalities Impact Needs Assessment (EINA) Preparatory Information.

This report was completed before the addition of preparatory Equalities Impact Needs Assessment (EINA) information to all needs assessments, considering the potential impact on groups, such as those of different age, sex, gender, sexuality, and ethnicity.

However, equalities issues were considered as part of the development of the report.

Document information

Published: January 2014

Reviewed: February 2015

For review: February 2018

Topic Lead: Anna Raleigh, Consultant in Public Health